Volume 7, Issue 2 (December 2021)

Elderly Health Journal 2021, 7(2): 91-98 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Izekenova A, Tolegenova A, Izekenova A, Rakhmatullina A. Impact Analysis of Coronavirus on Elderly Population in Worldwide and Kazakhstan. Elderly Health Journal 2021; 7 (2) :91-98

URL: http://ehj.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-240-en.html

URL: http://ehj.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-240-en.html

Department of Epidemiology with Course of HIV, Asfendiyarov Kazakh National Medical University, Almaty, Kazakhstan , atolegenova@alumni.nu.edu.kz

Full-Text [PDF 3548 kb]

(300 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (860 Views)

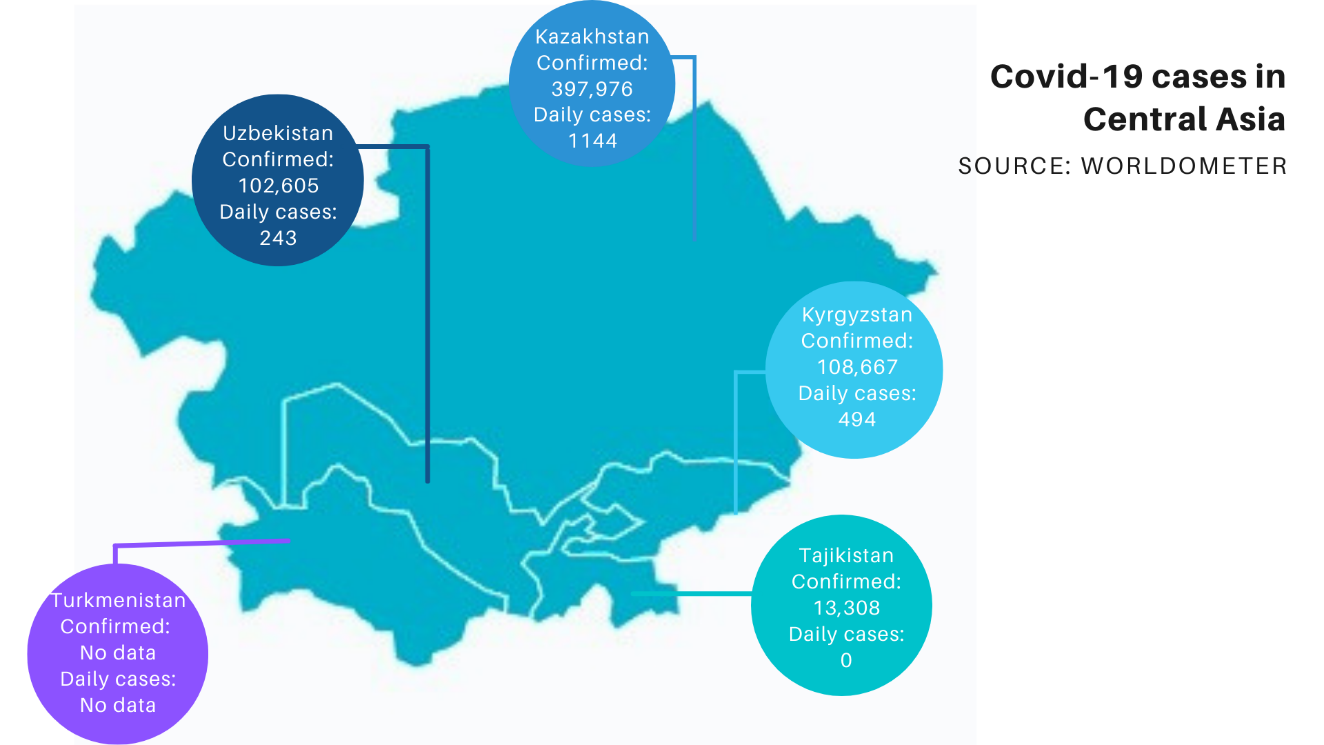

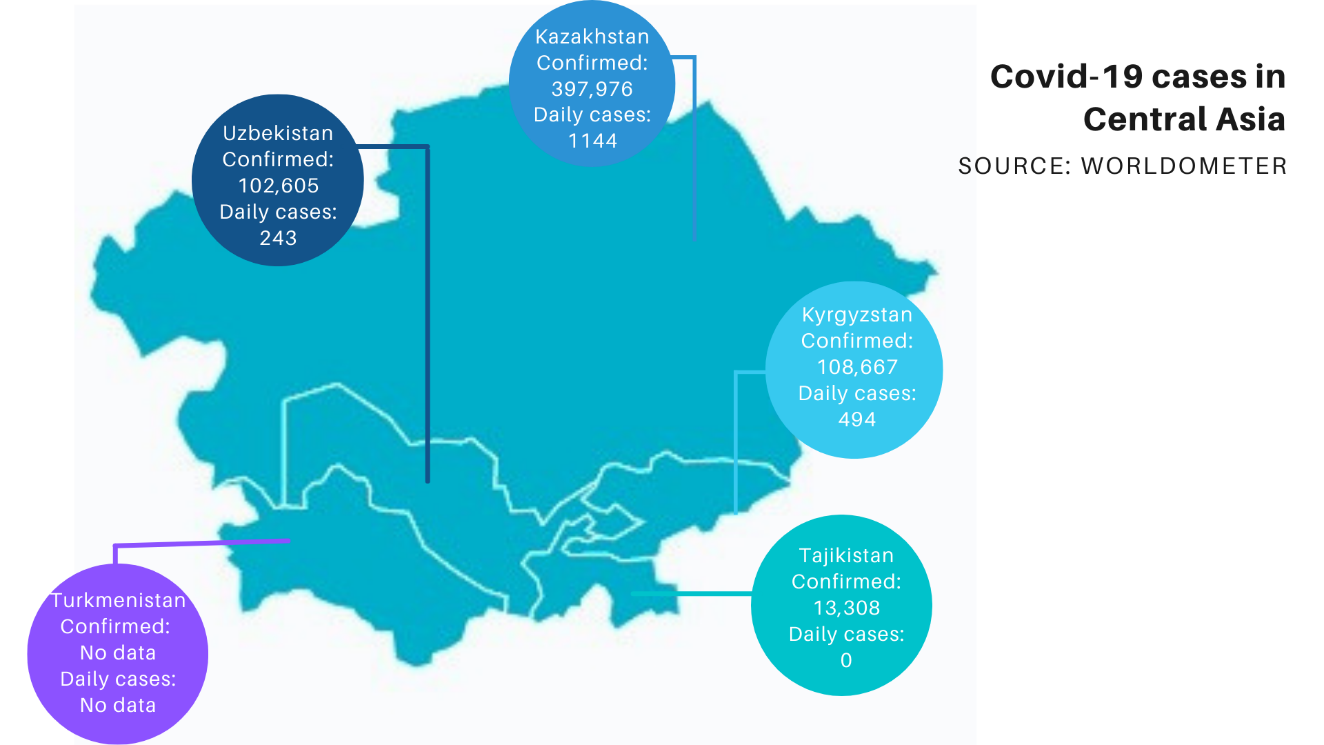

Figure 1. COVID-19 cases in Central Asian Countries by June 10, 2021

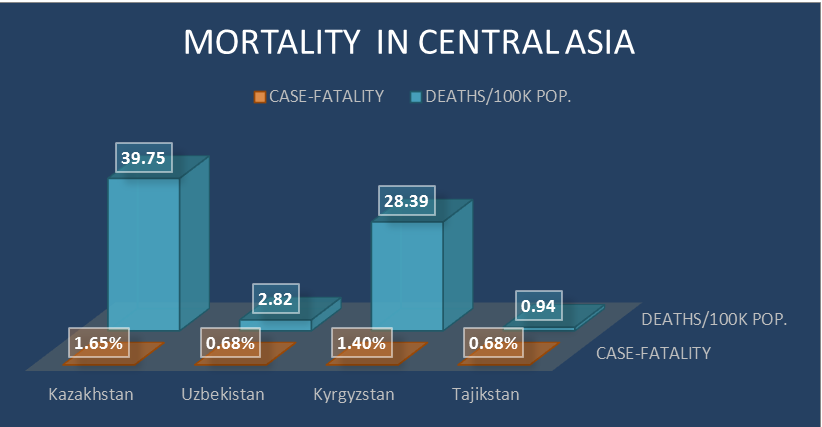

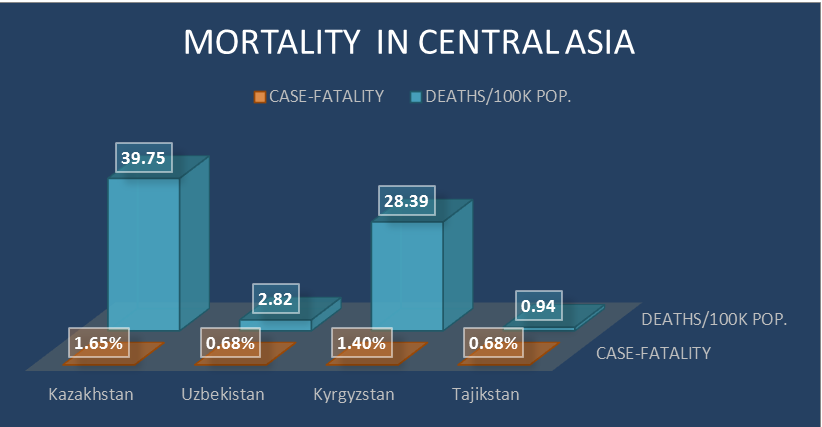

Figure 2. Mortality in Central Asian Countries by June 10, 2021 Discussion and Recommendations

Full-Text: (431 Views)

Impact Analysis of Coronavirus on Elderly Population in Worldwide and Kazakhstan

Assel Izekenova 1, Akbota Tolegenova *2, Aigulsum Izekenova 2, Alina Rakhmatullina 3

Received 30 Aug 2021

Accepted 18 Sep 2021

A B S T R A C T

Keywords: COVID-19, Pandemics, Aged, Review, Worldwide

Assel Izekenova 1, Akbota Tolegenova *2, Aigulsum Izekenova 2, Alina Rakhmatullina 3

- Department of Finance and Accounting, University of International Business, Kazakhstan

- Department of Epidemiology with Course of HIV, Asfendiyarov Kazakh National Medical University, Almaty, Kazakhstan

- Department of Finance and Accounting, University of International Business, Kazakhstan

Received 30 Aug 2021

Accepted 18 Sep 2021

A B S T R A C T

Covid-19 pandemics has affected the lives of all level population but brought an unprecedented threat to the health and daily life of the elderly population. Starting from Huanan Seafood Market in Wuhan, China, the virus spread to the world fleetingly, from 44 cases in January 2019 to 171,615,923 cases all around the world as of June 01, 2021, including Kazakhstan. SARS-CoV-2 positive patients had shown asymptomatic, mild, severe, and critical symptoms which brought to respiratory failure, shock, or multiorgan dysfunction in 5% of cases. The severity of the disease correlated with the older age and existing medical conditions, making the geriatric population more at hazard. A remarkable superiority of cases and deaths of Covid-19 was found within the elderly group, and particularly in those with pre-existing conditions and comorbidities, additionally to the immunosenescence and inflamm-aging. Studies done in the USA, Europe, and Asian countries showed a similar prevalence of the disease among adults and older people, but the mortality was extremely higher than in other age groups. Despite the similar prevalence, Kazakhstani researchers revealed a higher mortality rate (83.3%) than those countries. Therefore, the world, especially developing countries, needs additional advanced policies in vaccination policy, immediate testing, easy access to healthcare and information without ageist biases, income security, and more researches should be done that can address the issues, improve the lives and diminish the mortality of the geriatric population.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pandemics, Aged, Review, Worldwide

Copyright © 2020 Elderly Health Journal. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits copy and redistribute the material just in noncommercial usages, provided the original work is properly cite.

Introduction

Introduction

In winter 2019, everyone all around the world shuddered from the news about a novel virus that was found in Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, China. Forty-four patients with pneumonia of unknown etiology have been reported of which 11 patients had severe conditions as of 3 January 2020 (1). After one month the World Health Organization (WHO) officially named this infectious disease coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). It started to spread all over the world, and then in March, it w::as char::acterized as a pandemic. It was March 13 when the Kazakhstani government announced the first cases of this virus, and after 13 days, unfortunately, the first death was reported. More than 90 countries were closed for quarantine and Kazakhstan did the same, closing the two main cities first. However, in June, there was a sharp increase in morbidity which led to deaths four times more often than in the beginning, especially among the elderly population of Kazakhstan (2). Consequently, many studies have found age to be one of the main risk factors of severe conditions of COVID-19 (3). Nonetheless, to our knowledge, no studies were done exploring particularly the elderly population and COVID-19 in Kazakhstan. Therefore, this review aims to provide a brief review of the COVID-19COVID-19 situation in the aging population of Kazakhstan and compare it with other countries.

COVID-19

The coronaviruses (CoVs) come from a family of viruses with crown-like spikes on their surface and positive-sense single-stranded RNA with a genome length of nearly 30 kilobases (4, 5). Phylogenetic analysis of first identified coronavirus from Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan was found to have a distinct lineage with Bat-SARS-like coronaviruses that belong to the order Nidovirales, family Coronaviridae, genus Betacoronavirus, and subgenus Sarbecovirus (6). Until now, seven diverse coronaviruses were found to infect humans, and seasonally circulating four of them (HKU1, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-229E, and HCoV-NL63), cause mild common cold-type symptoms (5). The other two have caused large-scale pandemics, Severe acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV-1) and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV), which has killed 1632 people combined by inducing acute respiratory distress syndrome and death, with fatality rates 10% and 34% respectively (7, 8). The last, SARS-CoV-2, caused massive pandemics starting from 44 cases in January 2019 in China to 171,615,923 cases all around the world as of June 01, 2021 (9). After two months of the first cases in China, coronavirus reached Kazakhstan. On March 13, 2020, it became known about two infected passengers arriving from Europe. As of June 01, 2021, the number of confirmed cases in Kazakhstan has increased to 387,672 (10).

Risk factors

SARS-CoV-2 positive patients had shown asymptomatic, mild, severe, and critical symptoms. 33% of patients never developed any symptoms, while 81% reported having mild conditions (11, 12). Moreover, 14% of patients developed severe symptoms such as dyspnea, hypoxia, or > 50 percent lung involvement on imaging within the first two days (12). Lastly, critical symptoms like, respiratory failure, shock, or multiorgan dysfunction were identified in 5% of patients with coronavirus (12).

People with heart diseases, immunosuppression, malignancy, hypertension, and diabetes, were found to have more possibility to get severe COVID-19, whereas the elderly population, males, were also linked with advanced mortality (13). People living in poverty and with low income, migrants, are found to be the most affected population and found to be highly associated with an infection of SARS-CoV-2 (14). A study conducted by Almagro and Orane-hutchinson (2020) has also demonstrated that people with high-level social outreach and higher social interaction were more susceptible to the coronavirus (15). Last of all, high viral load and genetic factors such as genes encoding the ABO blood group were also associated with higher risk (16, 17).

One of the studies done in Kazakhstan showed that more than half of all cases of diseases were mild - 53.6%, moderate-severe - 36.7%, and severe cases - 8.8%. Patients, with critical conditions and needed mechanical ventilation, accounted for 0.9% of all cases (2). The severity of the disease correlated with the age of the respondents, with pneumonia, when patients visit the doctor, the duration of the disease, as well as presence of severe chronic diseases and old age (18).

Elderly population and COVID-19

Today, people worldwide are living longer and the estimated life expectancy is 73.2 years, 75.6 years for females, and 70.8 years for males, the highest numbers for the whole history of humankind (19). An advance in life expectancy is one of the most pompous successes of humanity and public health. The life expectancy at birth has raised significantly everywhere in the world. Traditionally, United Nations defines the elderly population as those aged 60 or 65 years or over (20), and in 2019, there were 703 million people aged 65 or over and about 1, 3 million of them live in Kazakhstan (20, 21). Japan has the highest proportion of elderly citizens, 28.14%, followed by Italy (22.68%), Greece (21.89%), and Finland (21.61%) (22). While in Kazakhstan it is significantly lower than those developed countries, only 7.7%, but it is still the highest among the Central Asian countries (average 5.2%) (20). By life expectancy, Hong Kong leads the list with 85.29 years, 88.17 for females and 82.38 for males, further Japan (85.03), and Macao (84.68), whereas Kazakhstan stands at the 105th place with 73.90 years,77.97 for females and 69.55 for males (19). Commonly, developed countries like Japan, have a higher life expectancy and elderly proportion due to some socio-economic factors such as more eminent standards of living, advanced healthcare systems, and more resources devoted to determinants of health (e.g. hygiene, housing, education) (23).

A remarkable superiority of cases and deaths of COVID-19 is found within the elderly group, and particularly in those with pre-existing conditions and comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, chronic respiratory disease, diabetes, and oncological disease spectrum (24). Further, various biological variations in the human body, specifically in the immune system, will be provoked when the person gets old, which are associated with age-related diseases and susceptibility to infections. Immunosenescence and inflamm-aging are also considered as key factors of vulnerability of the elderly population to the coronavirus (25). Immunosenescence is explained as dysfunction in innate immunity and more complex change in action across various immune responses, brought on by natural age advancement (26). Fail to respond effectively to the antigens is one of the signs of immunosenescence, which increases the vulnerability to infections (27). Furthermore, immunosenescence is also associated with inflamm-aging, the chronic low-grade inflammation, induced by a decreased capability to sustain inflammatory triggers including enhanced production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, acute-phase proteins, and oxidative stressors (28). These characteristics of immunosenescence and inflamm-aging are believed to be one of the reasons for higher rates of COVID-19 among the elderly.

Prevalence of COVID-19 Worldwide and in Kazakhstan by age groups

Worldwide

The coronavirus has infected 175,183,965 (2.23%) people worldwide as of June 10, 2021. The United States of America is ranked as the most infected country, with 34,264,727 people (10.30%) infected, followed by India with 29,183,121 (2.10%) confirmed cases for all age groups (29). Brazil, France, Turkey, Russia, UK, Italy, Argentina, and Germany follow these countries with the most confirmed cases. Whereas, according to the WHO, China had "114,929" cases out of 1.412 billion people (30).

Prevalence in young children has been reported in 65 studies from 11 different countries such as China, the USA, Iran, France, and so on. According to these studies, there were 474 cases of COVID-19 from China, 720 from the United States of America and Canada, eight from the United Kingdom, five from Iran, two from Malaysia, and one each from Vietnam, Lebanon, Iraq, France, and Germany. The 1135 COVID-19 cases ranged in age from 0 days to less than five years: 596 (53%) were less than one year old (infants) were. Of the 596 COVID-19 cases in newborns, five (1%) were newborns (31).

While the prevalence of adolescents and young adults among the four US states ranged from 1.2% to 2.2%. This study concluded that the prevalence of COVID-19 among young people is statistically significantly higher than the prevalence among older people (32). Another study from the United Kingdom found that self-reported prevalence of long-term COVID was highest among people aged 35 to 49 or 50 to 69 (2.5% and 2.4%, respectively). This indicator was statistically significantly higher in all age groups of adults than those aged 2 to 11 or 12 to 16 (33). What is more, in a study from India, the prevalence of COVID-19 among older adults with an average age of 67.5 was 27.7% and 8.5% of infected were hospitalized (34). In addition, the prevalence of infected older adults was 26.19% (33 confirmed cases out of 126 residents) at a skilled nursing facility (SNF) in Illinois, which is similar to the Indian study (35). However, a study in France found 65.9% of the prevalence of this disease among the elderly population (36). In another study from Connecticut, 2117 older adults (65 <) were tested and 601 (28.3%) were positive (37). Finally, according to the China Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the majority of confirmed cases (87%) were between the ages of 30 and 79, 1% were between the ages of nine and under, 1% were between the ages of 10 and 19, and 3% were 80 years of age or older (38).

Kazakhstan

The total number of confirmed cases of the disease in Kazakhstan by June 10, 2021, was 397,976, which is 2.10% of the total population of the country. Unfortunately, there have been only a few studies of COVID-19 and its prevalence in populations of different age groups. A study conducted among pediatric patients identified 650 children with COVID-19 under the age of 19. More than half (56.3%) of infected children were boys, and 122 (18.8%) were newborns and infants. They also stated that 85.8% of the children had no symptoms and only 0.6% of the cases were severe (39). Another study by Zhusupov and his team showed the age-related prevalence of COVID-19 among patients. According to the study, most of the patients were between the ages of 20 and 29 (29.2%). Then the disease was more common among people 30-39 years old (19.9%). Finally, the share of the elderly population over 60 years old was 8.2%, which is lesser than others (40). The overall prevalence of COVID-19 was found in the Sange project and was 4.6% for any symptoms, and the prevalence among patients with pneumonia was 3.8%. Moreover, they stated that the prevalence of infection was about 29.3% among people over 60 years old, while for the age group 30-39 years old - 26.4%, and among young people - 19.7%(41).

By June 10, 2021, Kazakhstan had the uppermost number of confirmed and daily new cases than all Central Asian countries: Uzbekistan, which had 102,605 confirmed cases, Kyrgyzstan 108,667 cases, and Tajikistan 13,308 cases on the same day (Figure 1) (58). Unfortunately, there are no data available for the Turkmenistan. Additionally, prevalence of population at age 60 and older among COVID-19 patients was found to be 8.1% in Uzbekistan, that was not as much of younger people at age 30-40 (56). This prevalence is very similar to the findings of Zhusupov’s study.

Mortality from COVID-19 Worldwide and in Kazakhstan by age groups

Worldwide

Globally, 3,777,496 deaths were recorded, resulting in a mortality rate of 47.99 per 100,000 population, and a case-fatality rate of 2.16%. As of May 1, an estimated 23,430 people have died out of a total population of 8,398,748 in the United States, bringing the overall death rate to date at 0.28%, which can be interpreted as 279 deaths per 100,000 population (42). According to the analysis of mortality by Johns Hopkins, the highest mortality rate by June 9, 2021 was recorded in Peru: the mortality rate was 574.45 per 100,000 people, and the case fatality rate was 9.4%. Hungary and Bosnia and Herzegovina follow with mortality rates of 305.87 and 286.58 per 100,000, respectively (43). According to the Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the death rate among the elderly was significantly higher - 95.1% of the total 1,979 deaths. Mortality was 5.59% in patients aged 70-79 years and 18.77% in patients ≥ 80 years old compared to 0.26% in patients aged 50-59%(44). A study from Sweden examined 274,712 adults aged 70, of whom 1,301 died due to COVID-19, bringing the death rate to 473.59 per 100,000 population(45). On 3 May 2020, in Malaysia, it was found that 99 of COVID-19 deaths were from the age group of 61–70 years with 32%, followed by the age group of 71–80 years with 19.2%, showing the highest rate of death among elderly (46).

Kazakhstan

By June 9, 2021, WHO had registered 7,465 deaths from both COVID-19 and pneumonia in Kazakhstan.

of these, 4124 deaths accounted for only COVID-19, resulting in a case fatality rate of 1.65 %, a crude mortality rate of 39.75 per 100,000 population (47). The results of one of the Kazakhstani studies showed an overall mortality rate of 1% and a higher mortality rate (11.2%) in patients over 60 years old and patients with cardiovascular pathology (40). Another study by Maukaeva and her team found that the mortality rate among patients over 60 years old is 83.3%, which is higher compared to the upper mentioned countries (48).

If we compare Kazakhstan by both case fatality and deaths per 100,000 population for all ages to other stans, then we can notice that it is also leading there (Figure 2) (58). A clinical study conducted in Uzbekistan have found a mortality rate of 48.9% among aged patients, while according to the Kyrgyzstani health government, this rate was 61.0%, highest compared to other age groups, but still less than rates in Kazakhstan (56, 57).

COVID-19

The coronaviruses (CoVs) come from a family of viruses with crown-like spikes on their surface and positive-sense single-stranded RNA with a genome length of nearly 30 kilobases (4, 5). Phylogenetic analysis of first identified coronavirus from Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan was found to have a distinct lineage with Bat-SARS-like coronaviruses that belong to the order Nidovirales, family Coronaviridae, genus Betacoronavirus, and subgenus Sarbecovirus (6). Until now, seven diverse coronaviruses were found to infect humans, and seasonally circulating four of them (HKU1, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-229E, and HCoV-NL63), cause mild common cold-type symptoms (5). The other two have caused large-scale pandemics, Severe acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV-1) and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV), which has killed 1632 people combined by inducing acute respiratory distress syndrome and death, with fatality rates 10% and 34% respectively (7, 8). The last, SARS-CoV-2, caused massive pandemics starting from 44 cases in January 2019 in China to 171,615,923 cases all around the world as of June 01, 2021 (9). After two months of the first cases in China, coronavirus reached Kazakhstan. On March 13, 2020, it became known about two infected passengers arriving from Europe. As of June 01, 2021, the number of confirmed cases in Kazakhstan has increased to 387,672 (10).

Risk factors

SARS-CoV-2 positive patients had shown asymptomatic, mild, severe, and critical symptoms. 33% of patients never developed any symptoms, while 81% reported having mild conditions (11, 12). Moreover, 14% of patients developed severe symptoms such as dyspnea, hypoxia, or > 50 percent lung involvement on imaging within the first two days (12). Lastly, critical symptoms like, respiratory failure, shock, or multiorgan dysfunction were identified in 5% of patients with coronavirus (12).

People with heart diseases, immunosuppression, malignancy, hypertension, and diabetes, were found to have more possibility to get severe COVID-19, whereas the elderly population, males, were also linked with advanced mortality (13). People living in poverty and with low income, migrants, are found to be the most affected population and found to be highly associated with an infection of SARS-CoV-2 (14). A study conducted by Almagro and Orane-hutchinson (2020) has also demonstrated that people with high-level social outreach and higher social interaction were more susceptible to the coronavirus (15). Last of all, high viral load and genetic factors such as genes encoding the ABO blood group were also associated with higher risk (16, 17).

One of the studies done in Kazakhstan showed that more than half of all cases of diseases were mild - 53.6%, moderate-severe - 36.7%, and severe cases - 8.8%. Patients, with critical conditions and needed mechanical ventilation, accounted for 0.9% of all cases (2). The severity of the disease correlated with the age of the respondents, with pneumonia, when patients visit the doctor, the duration of the disease, as well as presence of severe chronic diseases and old age (18).

Elderly population and COVID-19

Today, people worldwide are living longer and the estimated life expectancy is 73.2 years, 75.6 years for females, and 70.8 years for males, the highest numbers for the whole history of humankind (19). An advance in life expectancy is one of the most pompous successes of humanity and public health. The life expectancy at birth has raised significantly everywhere in the world. Traditionally, United Nations defines the elderly population as those aged 60 or 65 years or over (20), and in 2019, there were 703 million people aged 65 or over and about 1, 3 million of them live in Kazakhstan (20, 21). Japan has the highest proportion of elderly citizens, 28.14%, followed by Italy (22.68%), Greece (21.89%), and Finland (21.61%) (22). While in Kazakhstan it is significantly lower than those developed countries, only 7.7%, but it is still the highest among the Central Asian countries (average 5.2%) (20). By life expectancy, Hong Kong leads the list with 85.29 years, 88.17 for females and 82.38 for males, further Japan (85.03), and Macao (84.68), whereas Kazakhstan stands at the 105th place with 73.90 years,77.97 for females and 69.55 for males (19). Commonly, developed countries like Japan, have a higher life expectancy and elderly proportion due to some socio-economic factors such as more eminent standards of living, advanced healthcare systems, and more resources devoted to determinants of health (e.g. hygiene, housing, education) (23).

A remarkable superiority of cases and deaths of COVID-19 is found within the elderly group, and particularly in those with pre-existing conditions and comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, chronic respiratory disease, diabetes, and oncological disease spectrum (24). Further, various biological variations in the human body, specifically in the immune system, will be provoked when the person gets old, which are associated with age-related diseases and susceptibility to infections. Immunosenescence and inflamm-aging are also considered as key factors of vulnerability of the elderly population to the coronavirus (25). Immunosenescence is explained as dysfunction in innate immunity and more complex change in action across various immune responses, brought on by natural age advancement (26). Fail to respond effectively to the antigens is one of the signs of immunosenescence, which increases the vulnerability to infections (27). Furthermore, immunosenescence is also associated with inflamm-aging, the chronic low-grade inflammation, induced by a decreased capability to sustain inflammatory triggers including enhanced production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, acute-phase proteins, and oxidative stressors (28). These characteristics of immunosenescence and inflamm-aging are believed to be one of the reasons for higher rates of COVID-19 among the elderly.

Prevalence of COVID-19 Worldwide and in Kazakhstan by age groups

Worldwide

The coronavirus has infected 175,183,965 (2.23%) people worldwide as of June 10, 2021. The United States of America is ranked as the most infected country, with 34,264,727 people (10.30%) infected, followed by India with 29,183,121 (2.10%) confirmed cases for all age groups (29). Brazil, France, Turkey, Russia, UK, Italy, Argentina, and Germany follow these countries with the most confirmed cases. Whereas, according to the WHO, China had "114,929" cases out of 1.412 billion people (30).

Prevalence in young children has been reported in 65 studies from 11 different countries such as China, the USA, Iran, France, and so on. According to these studies, there were 474 cases of COVID-19 from China, 720 from the United States of America and Canada, eight from the United Kingdom, five from Iran, two from Malaysia, and one each from Vietnam, Lebanon, Iraq, France, and Germany. The 1135 COVID-19 cases ranged in age from 0 days to less than five years: 596 (53%) were less than one year old (infants) were. Of the 596 COVID-19 cases in newborns, five (1%) were newborns (31).

While the prevalence of adolescents and young adults among the four US states ranged from 1.2% to 2.2%. This study concluded that the prevalence of COVID-19 among young people is statistically significantly higher than the prevalence among older people (32). Another study from the United Kingdom found that self-reported prevalence of long-term COVID was highest among people aged 35 to 49 or 50 to 69 (2.5% and 2.4%, respectively). This indicator was statistically significantly higher in all age groups of adults than those aged 2 to 11 or 12 to 16 (33). What is more, in a study from India, the prevalence of COVID-19 among older adults with an average age of 67.5 was 27.7% and 8.5% of infected were hospitalized (34). In addition, the prevalence of infected older adults was 26.19% (33 confirmed cases out of 126 residents) at a skilled nursing facility (SNF) in Illinois, which is similar to the Indian study (35). However, a study in France found 65.9% of the prevalence of this disease among the elderly population (36). In another study from Connecticut, 2117 older adults (65 <) were tested and 601 (28.3%) were positive (37). Finally, according to the China Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the majority of confirmed cases (87%) were between the ages of 30 and 79, 1% were between the ages of nine and under, 1% were between the ages of 10 and 19, and 3% were 80 years of age or older (38).

Kazakhstan

The total number of confirmed cases of the disease in Kazakhstan by June 10, 2021, was 397,976, which is 2.10% of the total population of the country. Unfortunately, there have been only a few studies of COVID-19 and its prevalence in populations of different age groups. A study conducted among pediatric patients identified 650 children with COVID-19 under the age of 19. More than half (56.3%) of infected children were boys, and 122 (18.8%) were newborns and infants. They also stated that 85.8% of the children had no symptoms and only 0.6% of the cases were severe (39). Another study by Zhusupov and his team showed the age-related prevalence of COVID-19 among patients. According to the study, most of the patients were between the ages of 20 and 29 (29.2%). Then the disease was more common among people 30-39 years old (19.9%). Finally, the share of the elderly population over 60 years old was 8.2%, which is lesser than others (40). The overall prevalence of COVID-19 was found in the Sange project and was 4.6% for any symptoms, and the prevalence among patients with pneumonia was 3.8%. Moreover, they stated that the prevalence of infection was about 29.3% among people over 60 years old, while for the age group 30-39 years old - 26.4%, and among young people - 19.7%(41).

By June 10, 2021, Kazakhstan had the uppermost number of confirmed and daily new cases than all Central Asian countries: Uzbekistan, which had 102,605 confirmed cases, Kyrgyzstan 108,667 cases, and Tajikistan 13,308 cases on the same day (Figure 1) (58). Unfortunately, there are no data available for the Turkmenistan. Additionally, prevalence of population at age 60 and older among COVID-19 patients was found to be 8.1% in Uzbekistan, that was not as much of younger people at age 30-40 (56). This prevalence is very similar to the findings of Zhusupov’s study.

Mortality from COVID-19 Worldwide and in Kazakhstan by age groups

Worldwide

Globally, 3,777,496 deaths were recorded, resulting in a mortality rate of 47.99 per 100,000 population, and a case-fatality rate of 2.16%. As of May 1, an estimated 23,430 people have died out of a total population of 8,398,748 in the United States, bringing the overall death rate to date at 0.28%, which can be interpreted as 279 deaths per 100,000 population (42). According to the analysis of mortality by Johns Hopkins, the highest mortality rate by June 9, 2021 was recorded in Peru: the mortality rate was 574.45 per 100,000 people, and the case fatality rate was 9.4%. Hungary and Bosnia and Herzegovina follow with mortality rates of 305.87 and 286.58 per 100,000, respectively (43). According to the Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the death rate among the elderly was significantly higher - 95.1% of the total 1,979 deaths. Mortality was 5.59% in patients aged 70-79 years and 18.77% in patients ≥ 80 years old compared to 0.26% in patients aged 50-59%(44). A study from Sweden examined 274,712 adults aged 70, of whom 1,301 died due to COVID-19, bringing the death rate to 473.59 per 100,000 population(45). On 3 May 2020, in Malaysia, it was found that 99 of COVID-19 deaths were from the age group of 61–70 years with 32%, followed by the age group of 71–80 years with 19.2%, showing the highest rate of death among elderly (46).

Kazakhstan

By June 9, 2021, WHO had registered 7,465 deaths from both COVID-19 and pneumonia in Kazakhstan.

of these, 4124 deaths accounted for only COVID-19, resulting in a case fatality rate of 1.65 %, a crude mortality rate of 39.75 per 100,000 population (47). The results of one of the Kazakhstani studies showed an overall mortality rate of 1% and a higher mortality rate (11.2%) in patients over 60 years old and patients with cardiovascular pathology (40). Another study by Maukaeva and her team found that the mortality rate among patients over 60 years old is 83.3%, which is higher compared to the upper mentioned countries (48).

If we compare Kazakhstan by both case fatality and deaths per 100,000 population for all ages to other stans, then we can notice that it is also leading there (Figure 2) (58). A clinical study conducted in Uzbekistan have found a mortality rate of 48.9% among aged patients, while according to the Kyrgyzstani health government, this rate was 61.0%, highest compared to other age groups, but still less than rates in Kazakhstan (56, 57).

Figure 1. COVID-19 cases in Central Asian Countries by June 10, 2021

Figure 2. Mortality in Central Asian Countries by June 10, 2021 Discussion and Recommendations

Worldwide prevalence of COVID-19 had a similar trend with Kazakhstan, around 20-25%, causing a life-threatening danger for all countries despite their level of development. The pandemic is affecting the lives of all age groups, making everyone at risk of dying, and the elderly population is at a higher risk, as over 80 years old died at five times the average rate (49). Nevertheless, the observed mortality rate in conducted studies among elderly in Kazakhstan seems higher compared to the developed countries, drawing an assumption that the virus was more lethal to developing countries. An estimated 66% of older people have at least one existing health condition, which is with immunosenescence and inflamm-aging increase the risk of severity and death of COVID-19 among old people (50).

The Elderly people in their daily life can face ageism, discrimination of older people, during pandemics, and in the decision on medical care and therapies. A few investigations have analyzed predictors of ageist biases among health care workers, and most of them resulted in more negative attitudes towards older adults and less accurate knowledge about ageism among care providers (51). Furthermore, in most of the developing countries, they may also struggle due to the access to health services, their works, and their retirement pay. In 2017, Lancet Global Health has published that almost 16% of older persons were exposed to either psychological abuse (11.6%), financial abuse (6.8%), neglect (4.2%), physical abuse (2.6%), or sexual abuse (0.9%), which indeed can rise during the lockdowns (52). Therefore, a pandemic is not only threatening the health of the elderly population but also affecting their social life and mental health. Starting from the March of 2020, when everyone was informed about COVID-19, the prevalence of anxiety and depression intensified and in some countries even tripled. For instance, the prevalence of anxiety among all age groups tripled in Mexico from 15.0% to 50.0% and depression went from just 3.0% to 27.6% (53). The surge of mental health problems was also observed in South Korea, Sweden, United Kingdom, United States, and so on. The highest rates were stated to be associated with the intensifying COVID-19 losses and stringent confinement measures taken in the country. Yet, the prevalence of mental health among the elderly people was observed prominently. A Chinese investigation reported that 37.1% of the old participants had encountered depression and anxiety during the pandemic, while in the UK Household Longitudinal Study the mental distress of participants at age ≥ 70 years has risen from 11% to 18% (54, 55). While placing them on quarantine and restricting their does to reduce older people contraction of COVID-19, there may be vital unpropitious impacts on their health. This highlights the latent consequent influence of the COVID-19 on mental health of geriatric population and the importance of investigating this issue (59).

This COVID-19 pandemic can be defeated but only in so far as people behave in solidarity toward each other and take steps to protect and care for those most in jeopardy. First of all, in order to decrease the mortality rates, we need to identify immediately older people who are at a higher risk and those with health conditions and mental health, particularly those with limited mobility, and take urgent action to test them and give proper care. Then, the government needs to ensure that the elderly can have easy access to all health care systems in all care institutions and medical decisions without any stigma and ageist bias based on the best available scientific shreds of evidence. Ensure their income security, by furnishing corresponding pension and supply food, water, and other essentials, like personnel protective equipment, to those with economic hardships during the lockdowns. Specific measures should be also taken in order to help them to be continuously informed, get knowledge about their opportunities during pandemics, and enhance their access to information and communication technologies. Finally, health and social conditions during the pandemics and the effect of the virus on their physical health, mental health and daily life are still not properly studied and the existing data are disaggregated. Therefore, there should be done more research on these topics, to improve the work of health systems and care houses and to raise awareness of the root causes of high prevalence and mortality.

Conclusion

COVID-19 pandemics has affected the lives of all level population, but brought an unprecedented threat to the lives of geriatric population, due to additional health conditions, immunosenescence, inflamm-aging, and other factors. Researches that were conducted worldwide have revealed a higher prevalence and mortality rate among the elderly compared to the other age groups, showing their increased vulnerability to the virus. However, older persons in developing countries, like Kazakhstan can be at higher risk, as the mortality rate was found to be higher there. Therefore, the world needs additional advanced policies and more researches that can address the issues and improve the lives of the geriatric population during the pandemics and afterwards.

Funding

This research has been funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No.AP09058488)

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the support of Science Committee of Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan for the young scholar’s grant and University of International Business.

References

1. World Health Organization. COVID-19 – China. [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 July 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2020-DON229.

2. COVID-19 В КАЗАХСТАНЕ: МАСШТАБЫ ПРОБЛЕМЫ, ОЦЕНКА УСЛУГ ЗДРАВООХРАНЕНИЯ И СОЦИАЛЬНОЙ ЗАЩИТЫ [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 4]. Available from: http://sange.kz/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Sange_COVID-1-wave.pdf. [Russian]

3. Zheng Z, Peng F, Xu B, Zhao J, Liu H, Peng J, et al. Risk factors of critical & mortal COVID-19 cases: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Infection. 2020; 81(2): e16-e25.

4. Lauxmann MA, Santucci N, Autrán-Gómez A. The SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus and the COVID-19 outbreak. International Brazilian Journal of Urology. 2020; 46(suppl 1): 6-18.

5. Wang R, Simoneau C, Kulsuptrakul J, Bouhaddon M, Travisano KA, Hayashi JF, et al. Genetic screens identify host factors for SARS-CoV-2 and common cold coronaviruses. Cell. 2021; 184(1): 106-19.

6. Helmy Y, Fawzy M, Elaswad A, Sobieh A, Kenney S, Shehata A. The COVID-19 pandemic: a comprehensive review of taxonomy, genetics, epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and control. Journal Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(4): 1225.

7.Rabi FA, Al Zoubi MS, Kasasbeh GA, Salameh D M, Al-Nasser AD. SARS-CoV-2 and coronavirus disease 2019: what we know so far. Pathogens. 2020; 9(3): 231.

8. Mahase, E. Coronavirus: COVID-19 has killed more people than SARS and MERS combined, despite lower case fatality rate. British Medical Journal. 2020; 368.

9. Worldometer. COVID Live Update: 198,879,142 Cases and 4,238,503 Deaths from the Coronavirus [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 13]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.

10. Ситуация с коронавирусом официально. Coronavirus2020.kz. [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 6]. Available from: https://www.coronavirus2020.kz/.

11. Oran D, Topol E. The Proportion of SARS-CoV-2 infections that are asymptomatic. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2021; 174(5): 655-62. [Russian]

12. Wu Z, McGoogan J. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2020; 323(13): 1239-42.

13. Li J, Huang D, Zou B, Yang H, Zi Hui W, Rui F, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical characteristics, risk factors, and outcomes. Journal of Medical Virology. 2021; 93(3): 1449-58.

14. Sannigrahi S, Pilla F, Basu B, Basu A, Molter A. Examining the association between socio-demographic composition and COVID-19 fatalities in the European region using spatial regression approach. Sustain Cities and Society. 2020; 62: 1-14.

15. Almagro M, Orane-Hutchinson A. JUE insight: the determinants of the differential exposure to COVID-19 in New York city and their evolution over time. Journal of Urban Economics. 2020: 103293.

16. Liu Y, Yan L, Wan L, Xiang T, Le A, Liu J, et al. Viral dynamics in mild and severe cases of COVID-19. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2020; 20(6): 656-7.

17. Ray J, Schull M, Vermeulen M, Park A. Association between ABO and Rh blood groups and SARS-CoV-2 infection or severe COVID-19 illness. Annal of Internal Medicine. 2021; 174(3): 308-15.

18. Yegorov S, Goremykina M, Ivanova R, Good S, Babenko D, Shevtsov A, et al. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and virologic features of COVID-19 patients in Kazakhstan: A nation-wide retrospective cohort study. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe. 2021; 4: 100096.

19. Worldometer. Life expectancy by country and in the world population [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 8]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/demographics/life-expectancy/.

20. United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Ageing 2019 [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2021 July 8]. Available from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2019-Highlights.pdf.

21. Қазақстанның демографиялық жылнамалығы Демографический ежегодник Казахстана [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 8]. Available from: https://gender.stat.gov.kz/file/DemographicYearbookofKazakhstan.pdf. [Russian]

22. OECD Data. Elderly population. [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 8]. Available from: https://data.oecd.org/pop/elderly-population.htm.

23. Freeman T, Gesesew H, Bambra C, Giugliani ERJ, Popay J, Sanders D, et al. Why do some countries do better or worse in life expectancy relative to income? An analysis of Brazil, Ethiopia, and the United States of America. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2020; 19(1): 1-19.

24. Dhama K, Patel S, Kumar R, Rana J, Yatoo MI, Kumar A, et al. Geriatric population during the COVID-19 pandemic: problems, considerations, exigencies, and beyond. Frontiers in Public Health. 2020; 8: 1-8.

25. Bajaj V, Gadi N, Spihlman A, Wu S, Choi C, Moulton V. Aging, immunity, and COVID-19: how age influences the host immune response to coronavirus infections?. Frontiers in Physiology. 2021; 11: 1-23.

26. Aw D, Silva AB, Palmer DB. Immunosenescence: emerging challenges for an ageing population. Immunology. 2007; 120(4): 435-46.

27. Domingues R, Lippi A, Setz C, Outeiro TF, Krisko A. SARS-CoV-2, immunosenescence and inflammaging: partners in the COVID-19 crime. Aging. 2020; 12(18): 18778-89.

28. Aiello A, Farzaneh F, Candore G, Caruso C, Davinelli S, Gambino CM, et al. Immunosenescence and its hallmarks: how to oppose aging strategically? a review of potential options for therapeutic intervention. Frontiers in Immunology. 2019; 10: 1-19.

29. Worldometer. COVID Live Update: 175,183,965 Cases and 3,777, 286 Deaths from the Coronavirus [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 June 10]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.

30. World Health Organization. China: WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard With Vaccination Data [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 June 10]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/region/wpro/country/cn.

31. Bhuiyan M, Stiboy E, Hassan M, Chan M, Islam S, Haider N, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 infection in young children under five years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2021;3 9(4): 667-677.

32. Rumain B, Schneiderman M, Geliebter A. Prevalence of COVID-19 in adolescents and youth compared with older adults in states experiencing surges. PLoS One. 2021; 16(3): e0242587.

33. Office for National Statistics. Prevalence of ongoing symptoms following coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in the UK: 1 April 2021 [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 10]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/prevalenceofongoingsymptomsfollowingcoronaviruscovid19infectionintheuk/1april2021.

34. Ranjan A, Muraleedharan V. Equity and elderly health in India: reflections from 75th round National Sample Survey, 2017–18, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Globalization and Health. 2020; 16(1): 1-16.

35. Patel M, Chaisson LH, Borgetti S, Burdsall D, Chugh RK, Hoff C, et al. Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 mortality during an outbreak investigation in a skilled nursing facility. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020; 71(11): 2920-6.

36. Bernadou A, Bouges S, Catroux M, Rigaux JC, Laland C, Leveque N, et al. High impact of COVID-19 outbreak in a nursing home in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, France, March to April 2020. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2021; 21(1): 1-6.

37. Parikh S, O’Laughlin K, Ehrlich H, Campbell L, Harizaj A, Durante A, et al. Point prevalence testing of residents for SARS-CoV-2 in a subset of connecticut nursing homes. JAMA. 2020; 324(11): 1101-3.

38. Epidemiology Working Group for NCIP Epidemic Response, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020; 41(2): 145-51

39. Bayesheva D, Boranbayeva R, Turdalina B, Fakhradiyev I, Saliev T, Tanabayeva S, et al. COVID-19 in the paediatric population of Kazakhstan. Paediatrics and International Child Health. 2021; 41(1): 76-82.

40. Zhussupov B, Saliev T, Sarybayeva G, Altynbekov K, Tanabayeva, S, Altynbekov S, et al. Analysis of COVID-19 pandemics in Kazakhstan. Journal of Research in Health Sciences. 2021; 21(2): 1-7.

41. Forbres KZ. Центр исследований «Сандж» [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 30]. Available from: https://forbes.kz/authors/authorsid_1239. [Russian]

42. Worldometer. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Mortality Rate [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 June 10]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/coronavirus-death-rate/.

43. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Mortality Analyses [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 June 10]. Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality.

44.Central Disaster Management Headquarters. Coronavirus (COVID-19), Republic of Korea [Internet]. 202012 [cited 2021 May 29]; Available from: http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/en/

45. Brandén M, Aradhya S, Kolk M, Härkönen J, Drefahl S, Malmberg B, et al. Residential context and COVID-19 mortality among adults aged 70 years and older in Stockholm: a population-based, observational study using individual-level data. The Lancet Healthy Longevity. 2020; 1(2): e80-e8.

46. Chee S. COVID-19 pandemic: the lived experiences of older adults in aged care homes. Millennial Asia. 2020; 11(3): 299-317.

47. Worldometer. COVID Live Update: 175,183,965 Cases and 3,777,286 Deaths from the Coronavirus [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 June 10]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.

48. Maukayeva S, Karimova S. Epidemiologic character of COVID-19 in Kazakhstan: a preliminary report. Northern Clinics of Istanbul. 2020; 7(3): 210-3.

49. World Health Organization. COVID-19 strategy update 14 April 2020 [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 26]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/COVID-19-strategy-update---14-april-2020.

50. Clark A, Jit M, Warren-Gash C, Guthrie B, Wang H, Mercer SW, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of the population at increased risk of severe COVID-19 due to underlying health conditions in 2020: a modelling study. The Lancet Global Health. 2020; 8(8): e1003-e17.

51. Wyman MF, Shiovitz-Ezra S, Bengel J. (2018) Ageism in the Health Care System: Providers, Patients, and Systems. In: Ayalon L, Tesch-Römer C, editors. Contemporary Perspectives on Ageism. International Perspectives on Aging. vol 19. Springer, Cham; 2018. p. 193-212.

52. World Health Organization. Abuse of older people on the rise - 1 in 6 affected [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 31]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/14-06-2017-abuse-of-older-people-on-the-rise-1-in-6-affected.

53. OECD. Tackling the mental health impact of the COVID-19 crisis: An integrated, whole-of-society response [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 August 16]. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/tackling-the-mental-health-impact-of-the-COVID-19-crisis-an-integrated-whole-of-society-response-0ccafa0b/.

54. Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. General Psychiatry. 2020; 33(2):e100213.

55. Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, Hatch S, Hotopf M, John A, et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020; 7(10): 883-92.

56. Газета.uz. Статистика: возрастная структура заболеваемости и смертности от COVID-19 в Узбекистане [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 August 16]. Available from: https://www.gazeta.uz/ru/2020/09/06/covid-stats/. [Russian]

57. Sputnik. Никифорова В, Акопов П, Хроленко А, Кузьминых Ю. Минздрав назвал возраст умерших кыргызстанцев, у которых подтвердили COVID[Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 August 16]. Available from: https://ru.sputnik.kg/society/20200720/1049074427/kyrgyzstan-minzdrav-vozrast-smertnost.html. [Russian]

58. Worldometer. COVID Live Update: 208,057,863 Cases and 4,375,878 Deaths from the Coronavirus [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 10]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/#countries.

59. Al Dhaheri AS, Bataineh MF, Mohamad MN, Ajab A, Al Marzouqi A, Jarrar AH, et al. (2021)Impact of COVID-19 on mental health and quality of life: Is there any effect? A cross-sectional study of the MENA region. Plos One. 2021; 16(3): 1-17.

The Elderly people in their daily life can face ageism, discrimination of older people, during pandemics, and in the decision on medical care and therapies. A few investigations have analyzed predictors of ageist biases among health care workers, and most of them resulted in more negative attitudes towards older adults and less accurate knowledge about ageism among care providers (51). Furthermore, in most of the developing countries, they may also struggle due to the access to health services, their works, and their retirement pay. In 2017, Lancet Global Health has published that almost 16% of older persons were exposed to either psychological abuse (11.6%), financial abuse (6.8%), neglect (4.2%), physical abuse (2.6%), or sexual abuse (0.9%), which indeed can rise during the lockdowns (52). Therefore, a pandemic is not only threatening the health of the elderly population but also affecting their social life and mental health. Starting from the March of 2020, when everyone was informed about COVID-19, the prevalence of anxiety and depression intensified and in some countries even tripled. For instance, the prevalence of anxiety among all age groups tripled in Mexico from 15.0% to 50.0% and depression went from just 3.0% to 27.6% (53). The surge of mental health problems was also observed in South Korea, Sweden, United Kingdom, United States, and so on. The highest rates were stated to be associated with the intensifying COVID-19 losses and stringent confinement measures taken in the country. Yet, the prevalence of mental health among the elderly people was observed prominently. A Chinese investigation reported that 37.1% of the old participants had encountered depression and anxiety during the pandemic, while in the UK Household Longitudinal Study the mental distress of participants at age ≥ 70 years has risen from 11% to 18% (54, 55). While placing them on quarantine and restricting their does to reduce older people contraction of COVID-19, there may be vital unpropitious impacts on their health. This highlights the latent consequent influence of the COVID-19 on mental health of geriatric population and the importance of investigating this issue (59).

This COVID-19 pandemic can be defeated but only in so far as people behave in solidarity toward each other and take steps to protect and care for those most in jeopardy. First of all, in order to decrease the mortality rates, we need to identify immediately older people who are at a higher risk and those with health conditions and mental health, particularly those with limited mobility, and take urgent action to test them and give proper care. Then, the government needs to ensure that the elderly can have easy access to all health care systems in all care institutions and medical decisions without any stigma and ageist bias based on the best available scientific shreds of evidence. Ensure their income security, by furnishing corresponding pension and supply food, water, and other essentials, like personnel protective equipment, to those with economic hardships during the lockdowns. Specific measures should be also taken in order to help them to be continuously informed, get knowledge about their opportunities during pandemics, and enhance their access to information and communication technologies. Finally, health and social conditions during the pandemics and the effect of the virus on their physical health, mental health and daily life are still not properly studied and the existing data are disaggregated. Therefore, there should be done more research on these topics, to improve the work of health systems and care houses and to raise awareness of the root causes of high prevalence and mortality.

Conclusion

COVID-19 pandemics has affected the lives of all level population, but brought an unprecedented threat to the lives of geriatric population, due to additional health conditions, immunosenescence, inflamm-aging, and other factors. Researches that were conducted worldwide have revealed a higher prevalence and mortality rate among the elderly compared to the other age groups, showing their increased vulnerability to the virus. However, older persons in developing countries, like Kazakhstan can be at higher risk, as the mortality rate was found to be higher there. Therefore, the world needs additional advanced policies and more researches that can address the issues and improve the lives of the geriatric population during the pandemics and afterwards.

Funding

This research has been funded by the Science Committee of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No.AP09058488)

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the support of Science Committee of Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Kazakhstan for the young scholar’s grant and University of International Business.

References

1. World Health Organization. COVID-19 – China. [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 July 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2020-DON229.

2. COVID-19 В КАЗАХСТАНЕ: МАСШТАБЫ ПРОБЛЕМЫ, ОЦЕНКА УСЛУГ ЗДРАВООХРАНЕНИЯ И СОЦИАЛЬНОЙ ЗАЩИТЫ [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 4]. Available from: http://sange.kz/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Sange_COVID-1-wave.pdf. [Russian]

3. Zheng Z, Peng F, Xu B, Zhao J, Liu H, Peng J, et al. Risk factors of critical & mortal COVID-19 cases: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Infection. 2020; 81(2): e16-e25.

4. Lauxmann MA, Santucci N, Autrán-Gómez A. The SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus and the COVID-19 outbreak. International Brazilian Journal of Urology. 2020; 46(suppl 1): 6-18.

5. Wang R, Simoneau C, Kulsuptrakul J, Bouhaddon M, Travisano KA, Hayashi JF, et al. Genetic screens identify host factors for SARS-CoV-2 and common cold coronaviruses. Cell. 2021; 184(1): 106-19.

6. Helmy Y, Fawzy M, Elaswad A, Sobieh A, Kenney S, Shehata A. The COVID-19 pandemic: a comprehensive review of taxonomy, genetics, epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and control. Journal Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(4): 1225.

7.Rabi FA, Al Zoubi MS, Kasasbeh GA, Salameh D M, Al-Nasser AD. SARS-CoV-2 and coronavirus disease 2019: what we know so far. Pathogens. 2020; 9(3): 231.

8. Mahase, E. Coronavirus: COVID-19 has killed more people than SARS and MERS combined, despite lower case fatality rate. British Medical Journal. 2020; 368.

9. Worldometer. COVID Live Update: 198,879,142 Cases and 4,238,503 Deaths from the Coronavirus [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 13]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.

10. Ситуация с коронавирусом официально. Coronavirus2020.kz. [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 6]. Available from: https://www.coronavirus2020.kz/.

11. Oran D, Topol E. The Proportion of SARS-CoV-2 infections that are asymptomatic. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2021; 174(5): 655-62. [Russian]

12. Wu Z, McGoogan J. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2020; 323(13): 1239-42.

13. Li J, Huang D, Zou B, Yang H, Zi Hui W, Rui F, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical characteristics, risk factors, and outcomes. Journal of Medical Virology. 2021; 93(3): 1449-58.

14. Sannigrahi S, Pilla F, Basu B, Basu A, Molter A. Examining the association between socio-demographic composition and COVID-19 fatalities in the European region using spatial regression approach. Sustain Cities and Society. 2020; 62: 1-14.

15. Almagro M, Orane-Hutchinson A. JUE insight: the determinants of the differential exposure to COVID-19 in New York city and their evolution over time. Journal of Urban Economics. 2020: 103293.

16. Liu Y, Yan L, Wan L, Xiang T, Le A, Liu J, et al. Viral dynamics in mild and severe cases of COVID-19. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2020; 20(6): 656-7.

17. Ray J, Schull M, Vermeulen M, Park A. Association between ABO and Rh blood groups and SARS-CoV-2 infection or severe COVID-19 illness. Annal of Internal Medicine. 2021; 174(3): 308-15.

18. Yegorov S, Goremykina M, Ivanova R, Good S, Babenko D, Shevtsov A, et al. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and virologic features of COVID-19 patients in Kazakhstan: A nation-wide retrospective cohort study. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe. 2021; 4: 100096.

19. Worldometer. Life expectancy by country and in the world population [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 8]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/demographics/life-expectancy/.

20. United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Ageing 2019 [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2021 July 8]. Available from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2019-Highlights.pdf.

21. Қазақстанның демографиялық жылнамалығы Демографический ежегодник Казахстана [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 8]. Available from: https://gender.stat.gov.kz/file/DemographicYearbookofKazakhstan.pdf. [Russian]

22. OECD Data. Elderly population. [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 8]. Available from: https://data.oecd.org/pop/elderly-population.htm.

23. Freeman T, Gesesew H, Bambra C, Giugliani ERJ, Popay J, Sanders D, et al. Why do some countries do better or worse in life expectancy relative to income? An analysis of Brazil, Ethiopia, and the United States of America. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2020; 19(1): 1-19.

24. Dhama K, Patel S, Kumar R, Rana J, Yatoo MI, Kumar A, et al. Geriatric population during the COVID-19 pandemic: problems, considerations, exigencies, and beyond. Frontiers in Public Health. 2020; 8: 1-8.

25. Bajaj V, Gadi N, Spihlman A, Wu S, Choi C, Moulton V. Aging, immunity, and COVID-19: how age influences the host immune response to coronavirus infections?. Frontiers in Physiology. 2021; 11: 1-23.

26. Aw D, Silva AB, Palmer DB. Immunosenescence: emerging challenges for an ageing population. Immunology. 2007; 120(4): 435-46.

27. Domingues R, Lippi A, Setz C, Outeiro TF, Krisko A. SARS-CoV-2, immunosenescence and inflammaging: partners in the COVID-19 crime. Aging. 2020; 12(18): 18778-89.

28. Aiello A, Farzaneh F, Candore G, Caruso C, Davinelli S, Gambino CM, et al. Immunosenescence and its hallmarks: how to oppose aging strategically? a review of potential options for therapeutic intervention. Frontiers in Immunology. 2019; 10: 1-19.

29. Worldometer. COVID Live Update: 175,183,965 Cases and 3,777, 286 Deaths from the Coronavirus [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 June 10]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.

30. World Health Organization. China: WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard With Vaccination Data [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 June 10]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/region/wpro/country/cn.

31. Bhuiyan M, Stiboy E, Hassan M, Chan M, Islam S, Haider N, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 infection in young children under five years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2021;3 9(4): 667-677.

32. Rumain B, Schneiderman M, Geliebter A. Prevalence of COVID-19 in adolescents and youth compared with older adults in states experiencing surges. PLoS One. 2021; 16(3): e0242587.

33. Office for National Statistics. Prevalence of ongoing symptoms following coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in the UK: 1 April 2021 [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 10]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/prevalenceofongoingsymptomsfollowingcoronaviruscovid19infectionintheuk/1april2021.

34. Ranjan A, Muraleedharan V. Equity and elderly health in India: reflections from 75th round National Sample Survey, 2017–18, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Globalization and Health. 2020; 16(1): 1-16.

35. Patel M, Chaisson LH, Borgetti S, Burdsall D, Chugh RK, Hoff C, et al. Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 mortality during an outbreak investigation in a skilled nursing facility. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020; 71(11): 2920-6.

36. Bernadou A, Bouges S, Catroux M, Rigaux JC, Laland C, Leveque N, et al. High impact of COVID-19 outbreak in a nursing home in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, France, March to April 2020. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2021; 21(1): 1-6.

37. Parikh S, O’Laughlin K, Ehrlich H, Campbell L, Harizaj A, Durante A, et al. Point prevalence testing of residents for SARS-CoV-2 in a subset of connecticut nursing homes. JAMA. 2020; 324(11): 1101-3.

38. Epidemiology Working Group for NCIP Epidemic Response, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020; 41(2): 145-51

39. Bayesheva D, Boranbayeva R, Turdalina B, Fakhradiyev I, Saliev T, Tanabayeva S, et al. COVID-19 in the paediatric population of Kazakhstan. Paediatrics and International Child Health. 2021; 41(1): 76-82.

40. Zhussupov B, Saliev T, Sarybayeva G, Altynbekov K, Tanabayeva, S, Altynbekov S, et al. Analysis of COVID-19 pandemics in Kazakhstan. Journal of Research in Health Sciences. 2021; 21(2): 1-7.

41. Forbres KZ. Центр исследований «Сандж» [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 30]. Available from: https://forbes.kz/authors/authorsid_1239. [Russian]

42. Worldometer. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Mortality Rate [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 June 10]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/coronavirus-death-rate/.

43. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Mortality Analyses [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 June 10]. Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality.

44.Central Disaster Management Headquarters. Coronavirus (COVID-19), Republic of Korea [Internet]. 202012 [cited 2021 May 29]; Available from: http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/en/

45. Brandén M, Aradhya S, Kolk M, Härkönen J, Drefahl S, Malmberg B, et al. Residential context and COVID-19 mortality among adults aged 70 years and older in Stockholm: a population-based, observational study using individual-level data. The Lancet Healthy Longevity. 2020; 1(2): e80-e8.

46. Chee S. COVID-19 pandemic: the lived experiences of older adults in aged care homes. Millennial Asia. 2020; 11(3): 299-317.

47. Worldometer. COVID Live Update: 175,183,965 Cases and 3,777,286 Deaths from the Coronavirus [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 June 10]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.

48. Maukayeva S, Karimova S. Epidemiologic character of COVID-19 in Kazakhstan: a preliminary report. Northern Clinics of Istanbul. 2020; 7(3): 210-3.

49. World Health Organization. COVID-19 strategy update 14 April 2020 [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 26]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/COVID-19-strategy-update---14-april-2020.

50. Clark A, Jit M, Warren-Gash C, Guthrie B, Wang H, Mercer SW, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of the population at increased risk of severe COVID-19 due to underlying health conditions in 2020: a modelling study. The Lancet Global Health. 2020; 8(8): e1003-e17.

51. Wyman MF, Shiovitz-Ezra S, Bengel J. (2018) Ageism in the Health Care System: Providers, Patients, and Systems. In: Ayalon L, Tesch-Römer C, editors. Contemporary Perspectives on Ageism. International Perspectives on Aging. vol 19. Springer, Cham; 2018. p. 193-212.

52. World Health Organization. Abuse of older people on the rise - 1 in 6 affected [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 31]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/14-06-2017-abuse-of-older-people-on-the-rise-1-in-6-affected.

53. OECD. Tackling the mental health impact of the COVID-19 crisis: An integrated, whole-of-society response [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 August 16]. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/tackling-the-mental-health-impact-of-the-COVID-19-crisis-an-integrated-whole-of-society-response-0ccafa0b/.

54. Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. General Psychiatry. 2020; 33(2):e100213.

55. Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, Hatch S, Hotopf M, John A, et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020; 7(10): 883-92.

56. Газета.uz. Статистика: возрастная структура заболеваемости и смертности от COVID-19 в Узбекистане [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 August 16]. Available from: https://www.gazeta.uz/ru/2020/09/06/covid-stats/. [Russian]

57. Sputnik. Никифорова В, Акопов П, Хроленко А, Кузьминых Ю. Минздрав назвал возраст умерших кыргызстанцев, у которых подтвердили COVID[Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 August 16]. Available from: https://ru.sputnik.kg/society/20200720/1049074427/kyrgyzstan-minzdrav-vozrast-smertnost.html. [Russian]

58. Worldometer. COVID Live Update: 208,057,863 Cases and 4,375,878 Deaths from the Coronavirus [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 10]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/#countries.

59. Al Dhaheri AS, Bataineh MF, Mohamad MN, Ajab A, Al Marzouqi A, Jarrar AH, et al. (2021)Impact of COVID-19 on mental health and quality of life: Is there any effect? A cross-sectional study of the MENA region. Plos One. 2021; 16(3): 1-17.

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

General

Received: 2021/08/30 | Accepted: 2021/09/18 | Published: 2021/12/19

Received: 2021/08/30 | Accepted: 2021/09/18 | Published: 2021/12/19

References

1. World Health Organization. COVID-19 – China. [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 July 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2020-DON229.

2. COVID-19 В КАЗАХСТАНЕ: МАСШТАБЫ ПРОБЛЕМЫ, ОЦЕНКА УСЛУГ ЗДРАВООХРАНЕНИЯ И СОЦИАЛЬНОЙ ЗАЩИТЫ [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 4]. Available from: http://sange.kz/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Sange_COVID-1-wave.pdf. [Russian]

3. Zheng Z, Peng F, Xu B, Zhao J, Liu H, Peng J, et al. Risk factors of critical & mortal COVID-19 cases: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Infection. 2020; 81(2): e16-e25.

4. Lauxmann MA, Santucci N, Autrán-Gómez A. The SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus and the COVID-19 outbreak. International Brazilian Journal of Urology. 2020; 46(suppl 1): 6-18.

5. Wang R, Simoneau C, Kulsuptrakul J, Bouhaddon M, Travisano KA, Hayashi JF, et al. Genetic screens identify host factors for SARS-CoV-2 and common cold coronaviruses. Cell. 2021; 184(1): 106-19.

6. Helmy Y, Fawzy M, Elaswad A, Sobieh A, Kenney S, Shehata A. The COVID-19 pandemic: a comprehensive review of taxonomy, genetics, epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and control. Journal Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(4): 1225.

7. Rabi FA, Al Zoubi MS, Kasasbeh GA, Salameh D M, Al-Nasser AD. SARS-CoV-2 and coronavirus disease 2019: what we know so far. Pathogens. 2020; 9(3): 231.

8. Mahase, E. Coronavirus: COVID-19 has killed more people than SARS and MERS combined, despite lower case fatality rate. British Medical Journal. 2020; 368.

9. Worldometer. COVID Live Update: 198,879,142 Cases and 4,238,503 Deaths from the Coronavirus [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 13]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.

10. Ситуация с коронавирусом официально. Coronavirus2020.kz. [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 6]. Available from: https://www.coronavirus2020.kz/.

11. Oran D, Topol E. The Proportion of SARS-CoV-2 infections that are asymptomatic. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2021; 174(5): 655-62. [Russian]

12. Wu Z, McGoogan J. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2020; 323(13): 1239-42.

13. Li J, Huang D, Zou B, Yang H, Zi Hui W, Rui F, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical characteristics, risk factors, and outcomes. Journal of Medical Virology. 2021; 93(3): 1449-58.

14. Sannigrahi S, Pilla F, Basu B, Basu A, Molter A. Examining the association between socio-demographic composition and COVID-19 fatalities in the European region using spatial regression approach. Sustain Cities and Society. 2020; 62: 1-14.

15. Almagro M, Orane-Hutchinson A. JUE insight: the determinants of the differential exposure to COVID-19 in New York city and their evolution over time. Journal of Urban Economics. 2020: 103293.

16. Liu Y, Yan L, Wan L, Xiang T, Le A, Liu J, et al. Viral dynamics in mild and severe cases of COVID-19. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2020; 20(6): 656-7.

17. Ray J, Schull M, Vermeulen M, Park A. Association between ABO and Rh blood groups and SARS-CoV-2 infection or severe COVID-19 illness. Annal of Internal Medicine. 2021; 174(3): 308-15.

18. Yegorov S, Goremykina M, Ivanova R, Good S, Babenko D, Shevtsov A, et al. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and virologic features of COVID-19 patients in Kazakhstan: A nation-wide retrospective cohort study. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe. 2021; 4: 100096.

19. Worldometer. Life expectancy by country and in the world population [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 8]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/demographics/life-expectancy/.

20. United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Ageing 2019 [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2021 July 8]. Available from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2019-Highlights.pdf.

21. Қазақстанның демографиялық жылнамалығы Демографический ежегодник Казахстана [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 8]. Available from: https://gender.stat.gov.kz/file/DemographicYearbookofKazakhstan.pdf. [Russian]

22. OECD Data. Elderly population. [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 8]. Available from: https://data.oecd.org/pop/elderly-population.htm.

23. Freeman T, Gesesew H, Bambra C, Giugliani ERJ, Popay J, Sanders D, et al. Why do some countries do better or worse in life expectancy relative to income? An analysis of Brazil, Ethiopia, and the United States of America. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2020; 19(1): 1-19.

24. Dhama K, Patel S, Kumar R, Rana J, Yatoo MI, Kumar A, et al. Geriatric population during the COVID-19 pandemic: problems, considerations, exigencies, and beyond. Frontiers in Public Health. 2020; 8: 1-8.

25. Bajaj V, Gadi N, Spihlman A, Wu S, Choi C, Moulton V. Aging, immunity, and COVID-19: how age influences the host immune response to coronavirus infections?. Frontiers in Physiology. 2021; 11: 1-23.

26. Aw D, Silva AB, Palmer DB. Immunosenescence: emerging challenges for an ageing population. Immunology. 2007; 120(4): 435-46.

27. Domingues R, Lippi A, Setz C, Outeiro TF, Krisko A. SARS-CoV-2, immunosenescence and inflammaging: partners in the COVID-19 crime. Aging. 2020; 12(18): 18778-89.

28. Aiello A, Farzaneh F, Candore G, Caruso C, Davinelli S, Gambino CM, et al. Immunosenescence and its hallmarks: how to oppose aging strategically? a review of potential options for therapeutic intervention. Frontiers in Immunology. 2019; 10: 1-19.

29. Worldometer. COVID Live Update: 175,183,965 Cases and 3,777, 286 Deaths from the Coronavirus [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 June 10]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.

30. World Health Organization. China: WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard With Vaccination Data [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 June 10]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/region/wpro/country/cn.

31. Bhuiyan M, Stiboy E, Hassan M, Chan M, Islam S, Haider N, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 infection in young children under five years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2021;3 9(4): 667-677.

32. Rumain B, Schneiderman M, Geliebter A. Prevalence of COVID-19 in adolescents and youth compared with older adults in states experiencing surges. PLoS One. 2021; 16(3): e0242587.

33. Office for National Statistics. Prevalence of ongoing symptoms following coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in the UK: 1 April 2021 [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 10]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/prevalenceofongoingsymptomsfollowingcoronaviruscovid19infectionintheuk/1april2021.

34. Ranjan A, Muraleedharan V. Equity and elderly health in India: reflections from 75th round National Sample Survey, 2017–18, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Globalization and Health. 2020; 16(1): 1-16.

35. Patel M, Chaisson LH, Borgetti S, Burdsall D, Chugh RK, Hoff C, et al. Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 mortality during an outbreak investigation in a skilled nursing facility. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020; 71(11): 2920-6.

36. Bernadou A, Bouges S, Catroux M, Rigaux JC, Laland C, Leveque N, et al. High impact of COVID-19 outbreak in a nursing home in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, France, March to April 2020. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2021; 21(1): 1-6.

37. Parikh S, O’Laughlin K, Ehrlich H, Campbell L, Harizaj A, Durante A, et al. Point prevalence testing of residents for SARS-CoV-2 in a subset of connecticut nursing homes. JAMA. 2020; 324(11): 1101-3.

38. Epidemiology Working Group for NCIP Epidemic Response, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020; 41(2): 145-51

39. Bayesheva D, Boranbayeva R, Turdalina B, Fakhradiyev I, Saliev T, Tanabayeva S, et al. COVID-19 in the paediatric population of Kazakhstan. Paediatrics and International Child Health. 2021; 41(1): 76-82.

40. Zhussupov B, Saliev T, Sarybayeva G, Altynbekov K, Tanabayeva, S, Altynbekov S, et al. Analysis of COVID-19 pandemics in Kazakhstan. Journal of Research in Health Sciences. 2021; 21(2): 1-7.

41. Forbres KZ. Центр исследований «Сандж» [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 30]. Available from: https://forbes.kz/authors/authorsid_1239. [Russian]

42. Worldometer. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Mortality Rate [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 June 10]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/coronavirus-death-rate/.

43. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Mortality Analyses [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 June 10]. Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality.

44. Central Disaster Management Headquarters. Coronavirus (COVID-19), Republic of Korea [Internet]. 202012 [cited 2021 May 29]; Available from: http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/en/

45. Brandén M, Aradhya S, Kolk M, Härkönen J, Drefahl S, Malmberg B, et al. Residential context and COVID-19 mortality among adults aged 70 years and older in Stockholm: a population-based, observational study using individual-level data. The Lancet Healthy Longevity. 2020; 1(2): e80-e8.

46. Chee S. COVID-19 pandemic: the lived experiences of older adults in aged care homes. Millennial Asia. 2020; 11(3): 299-317.

47. Worldometer. COVID Live Update: 175,183,965 Cases and 3,777,286 Deaths from the Coronavirus [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 June 10]. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.

48. Maukayeva S, Karimova S. Epidemiologic character of COVID-19 in Kazakhstan: a preliminary report. Northern Clinics of Istanbul. 2020; 7(3): 210-3.

49. World Health Organization. COVID-19 strategy update 14 April 2020 [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 26]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/COVID-19-strategy-update---14-april-2020.

50. Clark A, Jit M, Warren-Gash C, Guthrie B, Wang H, Mercer SW, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of the population at increased risk of severe COVID-19 due to underlying health conditions in 2020: a modelling study. The Lancet Global Health. 2020; 8(8): e1003-e17.

51. Wyman MF, Shiovitz-Ezra S, Bengel J. (2018) Ageism in the Health Care System: Providers, Patients, and Systems. In: Ayalon L, Tesch-Römer C, editors. Contemporary Perspectives on Ageism. International Perspectives on Aging. vol 19. Springer, Cham; 2018. p. 193-212.

52. World Health Organization. Abuse of older people on the rise - 1 in 6 affected [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 July 31]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/14-06-2017-abuse-of-older-people-on-the-rise-1-in-6-affected.

53. OECD. Tackling the mental health impact of the COVID-19 crisis: An integrated, whole-of-society response [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 August 16]. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/tackling-the-mental-health-impact-of-the-COVID-19-crisis-an-integrated-whole-of-society-response-0ccafa0b/.

54. Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. General Psychiatry. 2020; 33(2):e100213.

55. Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, Hatch S, Hotopf M, John A, et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020; 7(10): 883-92.