Volume 11, Issue 2 (December 2025)

Elderly Health Journal 2025, 11(2): 160-168 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

baziyar Y, Jalali dehkordi K, Moradi Kelardeh B, Taghian F, Hosseini S A. Comparison of Voluntary, Forced, and Water-Resistance Exercise on Hippocampal BDNF and NGF Expression in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer's Disease. Elderly Health Journal 2025; 11 (2) :160-168

URL: http://ehj.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-361-en.html

URL: http://ehj.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-361-en.html

Younes Baziyar

, Khosro Jalali dehkordi *

, Khosro Jalali dehkordi *

, Baharak Moradi Kelardeh

, Baharak Moradi Kelardeh

, Farzaneh Taghian

, Farzaneh Taghian

, Seyed Ali Hosseini

, Seyed Ali Hosseini

, Khosro Jalali dehkordi *

, Khosro Jalali dehkordi *

, Baharak Moradi Kelardeh

, Baharak Moradi Kelardeh

, Farzaneh Taghian

, Farzaneh Taghian

, Seyed Ali Hosseini

, Seyed Ali Hosseini

Department of Sport Physiology, Isf.C., Islamic Azad University, Isfahan, Iran , khosrojalali@iau.ac.ir

Full-Text [PDF 493 kb]

(19 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (26 Views)

Table 1. Primer sequences of BDNF and NGF genes used in the qPCR assay

Table 2. Descriptive statistics (Mean ± SD) and Shapiro-wilk test of BDNF and NGF

Table 3. ANOVA results for changes in the expression of BDNF and NGF genes

Table 4. Results of Tukey’s post hoc test to compare the mean expression of BDNF and NGF genes in the research groups

* The mean difference is significant at the 0.05 level.

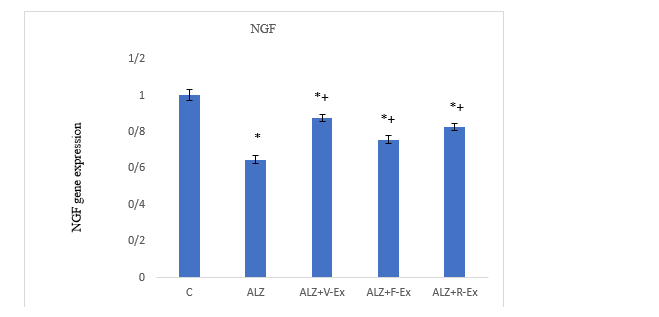

Figure1. Comparison of BDNF expression changes in the studied groups (*:Significant difference compared to the control group. +: Significant difference compared to the Alzheimer's group)

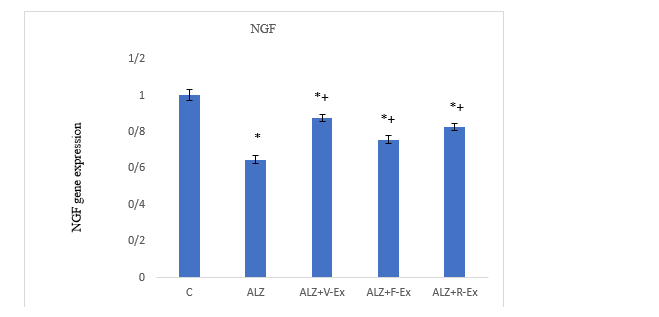

Figure 2. Comparison of BDNF expression changes in the studied groups (*:Significant difference compared to the control group. +: Significant difference compared to the Alzheimer's group)

Discussion

Full-Text: (4 Views)

Comparison of Voluntary, Forced, and Water-Resistance Exercise on Hippocampal BDNF and NGF Expression in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer's Disease

Younes Baziyar 1, Khosro Jalali Dehkordi 1* , Baharak Moradi Kelardeh 1, Farzaneh Taghian 1, Seyed Ali Hosseini 2

Received 31 May 2024

Accepted 17 Dec 2025

A B S T R A C T

Younes Baziyar 1, Khosro Jalali Dehkordi 1*

- Department of Sport Physiology, Isf.C., Islamic Azad University, Isfahan, Iran

- Department of Sport Physiology, Marv.C, Islamic Azad University, Marvdasht, Iran

Received 31 May 2024

Accepted 17 Dec 2025

A B S T R A C T

Introduction: Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive brain disorder that causes impairments in memory, thinking, and behavior. The aim of this study was to compare the effects of eight weeks of voluntary, forced, and resistance training in water on the expression of BDNF and NGF genes in the hippocampus of mice in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease.

Methods: Thirty male C57BL/6 mice weighing between 250-280 grams and aged over 15 months (elderly) were randomly divided into 5 groups: 1. Control, 2. Alzheimer’s disease (ALZ), 3. Voluntary training (ALZ+V-Ex), 4. Forced training (ALZ+F-Ex), and 5. Resistance training (ALZ+R-Ex). The training groups underwent their respective exercises for eight weeks, five days per week. The expression of BDNF and NGF genes was evaluated using Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test with a significance level of p < 0.05.

Results: Tukey’s post hoc test showed a significant decrease in BDNF and NGF gene expression in the ALZ group compared to the control group (p = 0.001). Significant increases in BDNF and NGF expression were observed in the ALZ+V-Ex (p = 0.001), ALZ+F-Ex (p = 0.001), and ALZ+R-Ex (p = 0.001) groups compared to the ALZ group. Among the exercise groups, BDNF and NGF expression was significantly higher in the ALZ+V-Ex group compared to ALZ+F-Ex (p = 0.001) and ALZ+R-Ex (p = 0.001), and expression was also significantly higher in ALZ+R-Ex compared to ALZ+F-Ex (p = 0.01(.

Conclusion: The results of this study showed that all three types of exercises—voluntary, forced, and water resistance training —significantly increased the expression of BDNF and NGF genes in mouse model of Alzheimer's disease.

Keywords: Voluntary Exercise, Forced Exercise, Water-Resistance Exercise, Alzheimer’s, BDNF, NGF

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits copy and redistribute the material just in noncommercial usages, provided the original work is properly cite.

Methods: Thirty male C57BL/6 mice weighing between 250-280 grams and aged over 15 months (elderly) were randomly divided into 5 groups: 1. Control, 2. Alzheimer’s disease (ALZ), 3. Voluntary training (ALZ+V-Ex), 4. Forced training (ALZ+F-Ex), and 5. Resistance training (ALZ+R-Ex). The training groups underwent their respective exercises for eight weeks, five days per week. The expression of BDNF and NGF genes was evaluated using Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post hoc test with a significance level of p < 0.05.

Results: Tukey’s post hoc test showed a significant decrease in BDNF and NGF gene expression in the ALZ group compared to the control group (p = 0.001). Significant increases in BDNF and NGF expression were observed in the ALZ+V-Ex (p = 0.001), ALZ+F-Ex (p = 0.001), and ALZ+R-Ex (p = 0.001) groups compared to the ALZ group. Among the exercise groups, BDNF and NGF expression was significantly higher in the ALZ+V-Ex group compared to ALZ+F-Ex (p = 0.001) and ALZ+R-Ex (p = 0.001), and expression was also significantly higher in ALZ+R-Ex compared to ALZ+F-Ex (p = 0.01(.

Conclusion: The results of this study showed that all three types of exercises—voluntary, forced, and water resistance training —significantly increased the expression of BDNF and NGF genes in mouse model of Alzheimer's disease.

Keywords: Voluntary Exercise, Forced Exercise, Water-Resistance Exercise, Alzheimer’s, BDNF, NGF

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits copy and redistribute the material just in noncommercial usages, provided the original work is properly cite.

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is one of the most common and serious neurodegenerative disorders, which is associated with a gradual decline in cognitive functions, including memory, attention, and executive skills (1). The pathological changes in this disease include accumulation of β-amyloid plaques, formation of tau neurofibrillary tangles, and widespread neuronal damage. These changes lead to reduced synaptic connectivity and ultimately to neuronal cell death (2).

Among the key molecules that maintain neuronal health and prevent AD progression are neurotrophic factors such as Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) and Nerve Growth Factor (NGF). These factors support neuron survival and enhance their health and function, thereby helping to protect against neural damage (3). Reduced levels of BDNF and its precursor have been observed in several brain regions and peripheral blood of AD patients (4). Decreased expression of BDNF and NGF in critical brain areas such as the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex is strongly associated with AD severity and cognitive decline (3). BDNF binds to the TrkB receptor and activates signalling pathways such as MAPK/ERK, PI3K/Akt, and PLCγ. Activation of these pathways strengthens neuronal survival, promotes their differentiation, and improves synaptic function (5) NGF also plays a key role in maintaining the health of cholinergic neurons by activating the TrkA receptor. If these signaling pathways become impaired, neurons lose their capacity for repair and response to injury. Over time, this condition can lead to accelerated neuronal degeneration and neuronal cell death (6).

In recent years, physical exercise has been studied as an effective way to improve cognitive functions and increase neurotrophic factors (7). Physical activity is an effective method to reduce or prevent the complications of aging. Regular exercise can improve cognitive abilities and brain health in older adults. Engaging in physical exercise can also stimulate the generation of new neurons in the brain; a process that research considers one of the most important strategies for combating neurodegenerative diseases. Therefore, physical activity is significant not only for bodily health but also for preserving and strengthening neural and cognitive health in the elderly (8). Recent studies have shown that regular physical activity increases the expression of BDNF and NGF genes in the brain. This increase in gene expression enhances synaptic plasticity, neurogenesis, and cognitive abilities. However, the nature and intensity of the exercise, the type of activity (voluntary or involuntary), and the environment in which it is performed (land or water) can have different effects on neurotrophic responses (7, 9, 10).

Voluntary exercises, in which animals engage in physical activity on their own motivation, reduces stress and optimally regulates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. These exercises also increase the expression of BDNF and NGF in various brain regions, especially the hippocampus (11, 12). Arslankiran et al., showed that voluntary exercise significantly increases the expression of BDNF and NGF compared to the control group. This exercise also improves spatial memory performance in an AD mouse model. These benefits are achieved through the reduction of stress hormones, such as cortisol, and the increase of neurotrophic factors (11). Compared to voluntary exercise, forced exercise increases stress levels. This elevated stress leads to the release of hippocampal corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). It is believed that the increased concentration of CRH causes cognitive impairments. Therefore, forced exercise may negatively affect both cognitive and non-cognitive functions (13).

This increase in stress during forced exercise may also reduce the benefits of elevated neurotrophins (14). On the other hand, resistance training (15, 16) and aquatic exercise (17) have been introduced as innovative and effective methods for increasing neurotrophin levels. The aquatic environment enables the performance of resistance exercises due to the natural resistance of water. This environment also reduces pressure on the joints, thereby lowering the risk of injury. Recent studies have shown that resistance training in water activates molecular pathways such as MAPK/ERK and PI3K/Akt. This activation ultimately increases the expression of BDNF and NGF and enhances neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity (17).

Neurotrophic factors play an important role in maintaining neural health. Physical exercise can regulate the expression of these factors. Accordingly, the present study was designed to compare the effects of voluntary, forced, and aquatic resistance exercise on the expression of BDNF and NGF genes in an AD mouse model. Examining the biochemical and molecular differences among these three types of exercise may help in designing targeted and low-stress rehabilitation programs. Such programs can ultimately improve the quality of life of patients with AD.

Methods

Study design and procedures

This experimental study aimed to compare the effects of eight weeks of voluntary, forced, and resistance aquatic training on the expression of BDNF and NGF genes in the hippocampus of mice with AD. All research procedures were conducted in accordance with laboratory animal care and handling protocols.

For this study, 30 males C57BL/6 mice weighing 250–280 g and with a mean elderly age of over 15 months were purchased and transferred to the laboratory. The mice were housed in the animal facility under standard environmental conditions at a temperature of 22–24°C. The humidity was maintained at 65% ± 5%, with a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle. The animals were also provided with a standard diet.

After one week of acclimatization to the animal facility, the mice were randomly divided into groups, with six mice in each group. The first group served as the control group (C). The second group consisted of AD mice treated with beta-amyloid (ALZ). The remaining three groups included AD mice subjected to voluntary exercise (ALZ + V-Ex), forced aquatic exercise (ALZ + F-Ex), and aquatic resistance training (ALZ + R-Ex).

Finally, 48 hours after the last training or treatment session, the mice were anesthetized using ketamine and xylazine. Subsequently, the brain tissue was extracted for further analyses and stored at −80°C.

Induction of AD

The Aβ-42 oligomer was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). Initially, this synthetic peptide was dissolved for 20 minutes in cold hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP). The solution was then vortexed for 10 minutes to allow the formation of Aβ-42 monomers. Subsequently, the monomers were pelleted using vacuum spin. The pelleted monomers were re-dissolved in 10% HFIP. The Aβ-42 solution was incubated for 48 hours at room temperature under continuous agitation. It was then centrifuged for 20 minutes at 4°C. The resulting supernatants were collected and transferred into pre-chilled tubes. Aβ-42 oligomers at a concentration of 50 μM were obtained after the complete evaporation of HFIP. These oligomers were stored at 4°C until use. In the next step, male C57BL/6 mice were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of ketamine and xylazine and were placed in a stereotaxic apparatus. In the AD model groups, 4 μL of the oligomer solution was bilaterally injected over a period of 12 minutes using a Hamilton syringe (18).

New object recognition test

To ensure that Alzheimer's was induced, the animals were given a novel object recognition test. This test was used to examine memory. Memory loss in the animals indicated that the disease had been successfully induced.

The novel object recognition test consisted of 4 stages over 4 days. On the first day, each rat was placed in an enclosure measuring 65 cm long, 45 cm wide, and 45 cm high for five minutes and freely explored the empty environment. No objects were placed in the enclosure during this stage. After 5 minutes, the animal was returned to the cage. 24 hours later, in the second phase, two objects identical in appearance (color, shape, and texture) were placed in opposite and symmetrical corners of the chamber at a distance of ten centimeters from the wall. Each mouse was familiarized with the identical objects for 10 minutes. The same thing was repeated on the third day. Finally, on the fourth day, the mice were given a memory test. In this way, one of the objects in the chamber was replaced with a new object with different appearance characteristics and the mouse was placed in the chamber. The healthy mice spent more time examining the new object. Sessions were recorded for later analysis. The amount of time each animal spent actively investigating the objects was manually scored. The difference in time between the two investigations was considered as the memory for novel object recognition (19).

Exercise protocols

Voluntary exercise

Mice in the ALZ+V-Ex group were housed in pairs in cages equipped with running wheels for eight weeks and had free access to the wheels. The devices were equipped with counters that recorded the distance traveled over a 24-hour period. The daily distance covered by the mice was recorded by the researcher at a fixed time each day (20).

Forced swimming exercise

Mice in the ALZ+F-Ex group underwent swimming-based training in a pool with an adjustable flow rate of 5 L/min. Initially, the mice completed a two-week acclimation period, during which the water flow was increased daily by 5% from 50% of the target intensity. The training protocol consisted of two phases: an acclimation phase and the main exercise phase. To reduce water-induced stress, mice were first familiarized with the pool environment during the second week, performing five consecutive 10-minute sessions. From the third week, the main training was conducted for eight weeks, five days per week, and 15 minutes per day at 32 ± 2°C. Training duration was gradually increased to apply the overload principle, reaching 60 minutes by the sixth week. During the seventh and eighth weeks, the swimming duration was maintained at 60 minutes, while the water flow reached its maximum intensity of 5 L/min. A 5-minute warm-up and cool-down period was included at the beginning and end of each session (21).

Resistance swimming exercise

The exercise protocol was performed in a swimming pool maintained at 32 ± 2°C. Mice swam for 60 minutes per day, five days per week, over eight weeks. During the first week, mice underwent a four-day gradual acclimation, followed by a progressive load test on day five. In this test, weight corresponding to 2% of the animal’s body weight was added every three minutes until exhaustion. The intensity of subsequent training sessions was set at 80% of the maximal weight achieved during the load test. Maximal weights were converted to percentages of body weight, and mice were weighed weekly to adjust the training workload. The average workload was approximately 4% of body weight (22).

Dissection and sampling

Mice were anesthetized 48 hours after the last exercise session following a 12-hour fast, using intraperitoneal ketamine and xylazine. Brain tissues were then collected, washed, weighed, and stored at –70°C for gene expression analysis. Relative expression of BDNF and NGF was measured by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) (18).

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from brain tissue using the manufacturer’s protocol (CinnaGen, Iran). RNA purity and concentration were assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA) at 260/280 nm. cDNA was synthesized according to the kit instructions and used for reverse transcription reactions. Specific primers for NGF and BDNF were designed using Oligo 7 and Beacon Designer 7 software. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed with SYBR Green to assess relative gene expression. Data analysis was conducted using the 2^−ΔΔCT method (23). Primer sequences are presented in Table 1.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 23. Normality was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used to compare groups. Results are expressed as mean ± SD, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

The study was also approved by the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, Isfahan (Khorasgan) Branch, under the code IR.IAU.KHUISF.REC.1404.373.

Results

Table 2 shows the mean and standard deviation of both genes in the experimental groups. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test revealed significant differences in hippocampal BDNF (F = 471.267, p =1.0E-3) and NGF (F = 179.74, p= 1.0E-3) expression among the groups (Table 3 and 4). Expression of both genes was significantly reduced in the ALZ group compared to the control group (p =1.0E-3), indicating the effect of AD induction. Exercise interventions significantly increased BDNF and NGF expression in the ALZ+V-Ex, ALZ+F-Ex, and ALZ+R-Ex groups compared to the C and ALZ group (p=1.0E-3). Among the exercise groups, the highest gene expression was observed in the ALZ+V-Ex group, followed by the ALZ+R-Ex group, both showing significantly higher levels than the ALZ+F-Ex group (p ≤ 0.01; Figures 1 and 2).

Among the key molecules that maintain neuronal health and prevent AD progression are neurotrophic factors such as Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) and Nerve Growth Factor (NGF). These factors support neuron survival and enhance their health and function, thereby helping to protect against neural damage (3). Reduced levels of BDNF and its precursor have been observed in several brain regions and peripheral blood of AD patients (4). Decreased expression of BDNF and NGF in critical brain areas such as the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex is strongly associated with AD severity and cognitive decline (3). BDNF binds to the TrkB receptor and activates signalling pathways such as MAPK/ERK, PI3K/Akt, and PLCγ. Activation of these pathways strengthens neuronal survival, promotes their differentiation, and improves synaptic function (5) NGF also plays a key role in maintaining the health of cholinergic neurons by activating the TrkA receptor. If these signaling pathways become impaired, neurons lose their capacity for repair and response to injury. Over time, this condition can lead to accelerated neuronal degeneration and neuronal cell death (6).

In recent years, physical exercise has been studied as an effective way to improve cognitive functions and increase neurotrophic factors (7). Physical activity is an effective method to reduce or prevent the complications of aging. Regular exercise can improve cognitive abilities and brain health in older adults. Engaging in physical exercise can also stimulate the generation of new neurons in the brain; a process that research considers one of the most important strategies for combating neurodegenerative diseases. Therefore, physical activity is significant not only for bodily health but also for preserving and strengthening neural and cognitive health in the elderly (8). Recent studies have shown that regular physical activity increases the expression of BDNF and NGF genes in the brain. This increase in gene expression enhances synaptic plasticity, neurogenesis, and cognitive abilities. However, the nature and intensity of the exercise, the type of activity (voluntary or involuntary), and the environment in which it is performed (land or water) can have different effects on neurotrophic responses (7, 9, 10).

Voluntary exercises, in which animals engage in physical activity on their own motivation, reduces stress and optimally regulates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. These exercises also increase the expression of BDNF and NGF in various brain regions, especially the hippocampus (11, 12). Arslankiran et al., showed that voluntary exercise significantly increases the expression of BDNF and NGF compared to the control group. This exercise also improves spatial memory performance in an AD mouse model. These benefits are achieved through the reduction of stress hormones, such as cortisol, and the increase of neurotrophic factors (11). Compared to voluntary exercise, forced exercise increases stress levels. This elevated stress leads to the release of hippocampal corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). It is believed that the increased concentration of CRH causes cognitive impairments. Therefore, forced exercise may negatively affect both cognitive and non-cognitive functions (13).

This increase in stress during forced exercise may also reduce the benefits of elevated neurotrophins (14). On the other hand, resistance training (15, 16) and aquatic exercise (17) have been introduced as innovative and effective methods for increasing neurotrophin levels. The aquatic environment enables the performance of resistance exercises due to the natural resistance of water. This environment also reduces pressure on the joints, thereby lowering the risk of injury. Recent studies have shown that resistance training in water activates molecular pathways such as MAPK/ERK and PI3K/Akt. This activation ultimately increases the expression of BDNF and NGF and enhances neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity (17).

Neurotrophic factors play an important role in maintaining neural health. Physical exercise can regulate the expression of these factors. Accordingly, the present study was designed to compare the effects of voluntary, forced, and aquatic resistance exercise on the expression of BDNF and NGF genes in an AD mouse model. Examining the biochemical and molecular differences among these three types of exercise may help in designing targeted and low-stress rehabilitation programs. Such programs can ultimately improve the quality of life of patients with AD.

Methods

Study design and procedures

This experimental study aimed to compare the effects of eight weeks of voluntary, forced, and resistance aquatic training on the expression of BDNF and NGF genes in the hippocampus of mice with AD. All research procedures were conducted in accordance with laboratory animal care and handling protocols.

For this study, 30 males C57BL/6 mice weighing 250–280 g and with a mean elderly age of over 15 months were purchased and transferred to the laboratory. The mice were housed in the animal facility under standard environmental conditions at a temperature of 22–24°C. The humidity was maintained at 65% ± 5%, with a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle. The animals were also provided with a standard diet.

After one week of acclimatization to the animal facility, the mice were randomly divided into groups, with six mice in each group. The first group served as the control group (C). The second group consisted of AD mice treated with beta-amyloid (ALZ). The remaining three groups included AD mice subjected to voluntary exercise (ALZ + V-Ex), forced aquatic exercise (ALZ + F-Ex), and aquatic resistance training (ALZ + R-Ex).

Finally, 48 hours after the last training or treatment session, the mice were anesthetized using ketamine and xylazine. Subsequently, the brain tissue was extracted for further analyses and stored at −80°C.

Induction of AD

The Aβ-42 oligomer was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). Initially, this synthetic peptide was dissolved for 20 minutes in cold hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP). The solution was then vortexed for 10 minutes to allow the formation of Aβ-42 monomers. Subsequently, the monomers were pelleted using vacuum spin. The pelleted monomers were re-dissolved in 10% HFIP. The Aβ-42 solution was incubated for 48 hours at room temperature under continuous agitation. It was then centrifuged for 20 minutes at 4°C. The resulting supernatants were collected and transferred into pre-chilled tubes. Aβ-42 oligomers at a concentration of 50 μM were obtained after the complete evaporation of HFIP. These oligomers were stored at 4°C until use. In the next step, male C57BL/6 mice were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of ketamine and xylazine and were placed in a stereotaxic apparatus. In the AD model groups, 4 μL of the oligomer solution was bilaterally injected over a period of 12 minutes using a Hamilton syringe (18).

New object recognition test

To ensure that Alzheimer's was induced, the animals were given a novel object recognition test. This test was used to examine memory. Memory loss in the animals indicated that the disease had been successfully induced.

The novel object recognition test consisted of 4 stages over 4 days. On the first day, each rat was placed in an enclosure measuring 65 cm long, 45 cm wide, and 45 cm high for five minutes and freely explored the empty environment. No objects were placed in the enclosure during this stage. After 5 minutes, the animal was returned to the cage. 24 hours later, in the second phase, two objects identical in appearance (color, shape, and texture) were placed in opposite and symmetrical corners of the chamber at a distance of ten centimeters from the wall. Each mouse was familiarized with the identical objects for 10 minutes. The same thing was repeated on the third day. Finally, on the fourth day, the mice were given a memory test. In this way, one of the objects in the chamber was replaced with a new object with different appearance characteristics and the mouse was placed in the chamber. The healthy mice spent more time examining the new object. Sessions were recorded for later analysis. The amount of time each animal spent actively investigating the objects was manually scored. The difference in time between the two investigations was considered as the memory for novel object recognition (19).

Exercise protocols

Voluntary exercise

Mice in the ALZ+V-Ex group were housed in pairs in cages equipped with running wheels for eight weeks and had free access to the wheels. The devices were equipped with counters that recorded the distance traveled over a 24-hour period. The daily distance covered by the mice was recorded by the researcher at a fixed time each day (20).

Forced swimming exercise

Mice in the ALZ+F-Ex group underwent swimming-based training in a pool with an adjustable flow rate of 5 L/min. Initially, the mice completed a two-week acclimation period, during which the water flow was increased daily by 5% from 50% of the target intensity. The training protocol consisted of two phases: an acclimation phase and the main exercise phase. To reduce water-induced stress, mice were first familiarized with the pool environment during the second week, performing five consecutive 10-minute sessions. From the third week, the main training was conducted for eight weeks, five days per week, and 15 minutes per day at 32 ± 2°C. Training duration was gradually increased to apply the overload principle, reaching 60 minutes by the sixth week. During the seventh and eighth weeks, the swimming duration was maintained at 60 minutes, while the water flow reached its maximum intensity of 5 L/min. A 5-minute warm-up and cool-down period was included at the beginning and end of each session (21).

Resistance swimming exercise

The exercise protocol was performed in a swimming pool maintained at 32 ± 2°C. Mice swam for 60 minutes per day, five days per week, over eight weeks. During the first week, mice underwent a four-day gradual acclimation, followed by a progressive load test on day five. In this test, weight corresponding to 2% of the animal’s body weight was added every three minutes until exhaustion. The intensity of subsequent training sessions was set at 80% of the maximal weight achieved during the load test. Maximal weights were converted to percentages of body weight, and mice were weighed weekly to adjust the training workload. The average workload was approximately 4% of body weight (22).

Dissection and sampling

Mice were anesthetized 48 hours after the last exercise session following a 12-hour fast, using intraperitoneal ketamine and xylazine. Brain tissues were then collected, washed, weighed, and stored at –70°C for gene expression analysis. Relative expression of BDNF and NGF was measured by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) (18).

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from brain tissue using the manufacturer’s protocol (CinnaGen, Iran). RNA purity and concentration were assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA) at 260/280 nm. cDNA was synthesized according to the kit instructions and used for reverse transcription reactions. Specific primers for NGF and BDNF were designed using Oligo 7 and Beacon Designer 7 software. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed with SYBR Green to assess relative gene expression. Data analysis was conducted using the 2^−ΔΔCT method (23). Primer sequences are presented in Table 1.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 23. Normality was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used to compare groups. Results are expressed as mean ± SD, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

The study was also approved by the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, Isfahan (Khorasgan) Branch, under the code IR.IAU.KHUISF.REC.1404.373.

Results

Table 2 shows the mean and standard deviation of both genes in the experimental groups. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test revealed significant differences in hippocampal BDNF (F = 471.267, p =1.0E-3) and NGF (F = 179.74, p= 1.0E-3) expression among the groups (Table 3 and 4). Expression of both genes was significantly reduced in the ALZ group compared to the control group (p =1.0E-3), indicating the effect of AD induction. Exercise interventions significantly increased BDNF and NGF expression in the ALZ+V-Ex, ALZ+F-Ex, and ALZ+R-Ex groups compared to the C and ALZ group (p=1.0E-3). Among the exercise groups, the highest gene expression was observed in the ALZ+V-Ex group, followed by the ALZ+R-Ex group, both showing significantly higher levels than the ALZ+F-Ex group (p ≤ 0.01; Figures 1 and 2).

Table 1. Primer sequences of BDNF and NGF genes used in the qPCR assay

| Sizes (bp) | Primer Sequences | Genes |

| 111 | Forward: 5ʹ- GTTTTGCCAAGGACGCAGCTTTC-3ʹ | NGF |

| Reverse: 5ʹ- GTTCTGCCTGTACGCCGATCAA-3ʹ | ||

| 106 | Forward: 5ʹ-CCACTAAGATACATCATAGC -3ʹ | BDNF |

| Reverse: 5ʹ-CAGAACAGAACAGAACCA-3ʹ |

Table 2. Descriptive statistics (Mean ± SD) and Shapiro-wilk test of BDNF and NGF

| N | Mean ± SD | Shapiro-wilk (p-value) | ||

| BDNF | C | 6 | 1.01 ± 0.03 | 0.80 |

| ALZ | 6 | 0.45 ± 0.02 | 0.80 | |

| ALZ+V-Ex | 6 | 0.84 ± 0.03 | 0.80 | |

| ALZ+F-Ex | 6 | 0.70 ± 0.02 | 0.80 | |

| ALZ+R-Ex | 6 | 0.80 ± 0.02 | 0.80 | |

| NGF | C | 6 | 1.01 ± 0.03 | 0.80 |

| ALZ | 6 | 0.65 ± 0.02 | 0.80 | |

| ALZ+V-Ex | 6 | 0.88 ± 0.02 | 0.80 | |

| ALZ+F-Ex | 6 | 0.76 ± 0.02 | 0.80 | |

| ALZ+R-Ex | 6 | 0.83 ± 0.02 | 0.80 | |

Table 3. ANOVA results for changes in the expression of BDNF and NGF genes

| Mean Square |

df | Mean Square | F | p | Eta-squared η² | ||

| BDNF | Between Groups | 1.01 | 4 | 0.25 | 471.27 | 1.0E-3 | 0.98 |

| Within Groups | 0.01 | 25 | 1.0 E -3 | ||||

| Total | 1.03 | 29 | |||||

| NGF | Between Groups | 0.42 | 4 | 0.11 | 179.74 | 1.0E-3 | 0.96 |

| Within Groups | 0.02 | 25 | 1.0 E -3 | ||||

| Total | 0.44 | 29 | |||||

Table 4. Results of Tukey’s post hoc test to compare the mean expression of BDNF and NGF genes in the research groups

| (J) group | (J) group | Mean Difference (I-J) ± SD | p | ||

| BDNF | C | ALZ | 0.55* ± 0.01 | 1.0E-3 | |

| ALZ+V-Ex | 0.15* ± 0.01 | 1.0E-3 | |||

| ALZ+F-Ex | 0.30* ± 0.01 | 1.0E-3 | |||

| ALZ+R-Ex | 0.20* ± 0.01 | 1.0E-3 | |||

| ALZ | ALZ+V-Ex | -0.40* ± 0.01 | 1.0E-3 | ||

| ALZ+F-Ex | -0.25* ± 0.01 | 1.0E-3 | |||

| ALZ+R-Ex | -0.35* ± 0.01 | 1.0E-3 | |||

| ALZ+V-Ex | ALZ+F-Ex | 0.15* ± 0.01 | 1.0E-3 | ||

| ALZ+R-Ex | 0.05* ± 0.01 | 0.01 | |||

| ALZ+F-Ex | ALZ+R-Ex | -0.10* ± 0.01 | 1.0E-3 | ||

| NGF | C | ALZ | 0.36* ± 0.01 | 1.0E-3 | |

| ALZ+V-Ex | 0.13* ± 0.01 | 1.0E-3 | |||

| ALZ+F-Ex | 0.25* ± 0.01 | 1.0E-3 | |||

| ALZ+R-Ex | 0.18* ± 0.01 | 1.0E-3 | |||

| ALZ | ALZ+V-Ex | -0.23* ± 0.01 | 1.0E-3 | ||

| ALZ+F-Ex | -0.11* ± 0.01 | 1.0E-3 | |||

| ALZ+R-Ex | -0.18* ± 0.01 | 1.0E-3 | |||

| ALZ+V-Ex | ALZ+F-Ex | 0.12* ± 0.01 | 1.0E-3 | ||

| ALZ+R-Ex | 0.05* ± 0.01 | 0.01 | |||

| ALZ+F-Ex | ALZ+R-Ex | -0.07* ± 0.01 | 1.0E-3 | ||

Figure1. Comparison of BDNF expression changes in the studied groups (*:Significant difference compared to the control group. +: Significant difference compared to the Alzheimer's group)

Figure 2. Comparison of BDNF expression changes in the studied groups (*:Significant difference compared to the control group. +: Significant difference compared to the Alzheimer's group)

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrated that all three types of exercise—voluntary, forced, and resistance swimming significantly increased the expression of BDNF and NGF genes in AD model mice. The greatest increase was observed in the voluntary exercise group, while the resistance swimming group exhibited higher gene expression than the forced swimming group. These findings are consistent with previous studies and confirm the positive role of exercise in improving cognitive function and enhancing BDNF and NGF expression.

Consistent with our findings, Peng et al., reported that aerobic exercise activates the PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β pathway, reducing neuronal apoptosis and improving cognitive function in AD mouse models (24). This is in line with the increased BDNF expression observed in the present study, as BDNF plays a central role in PI3K/Akt pathway activation. Similarly, long-term voluntary running has been shown to enhance cognitive performance via the BDNF/PI3K/Akt/CREB signaling pathway. Based on evidence from previous studies, voluntary exercise is generally associated with lower stress and more natural psychological engagement, which can enhance the activation of neurotrophic pathways, including BDNF and NGF. Conversely, forced exercise may elicit chronic stress, leading to elevated corticosterone or cortisol levels, which can suppress the upregulation of these neurotrophic factors (25).

Recent studies have highlighted the crucial role of molecular pathways, including BDNF-TrkB and PI3K/Akt, in mediating exercise-induced improvements in cognitive deficits. Exercise generally upregulates BDNF expression, which binds to the TrkB receptor and activates multiple downstream signaling pathways, including PI3K/Akt. These pathways promote neuronal survival, enhance synaptic plasticity, and reduce inflammation, collectively contributing to improved cognitive function (26). Li et al., investigated the effects of voluntary wheel running and involuntary treadmill exercise in an AD mouse model and reported that both exercise modalities increased BDNF protein levels (27). Similarly, Wang et al., demonstrated that four weeks of moderate treadmill exercise enhanced learning and memory, accompanied by increased hippocampal BDNF production and dendritic density (28). Medhat et al., examined the combined effects of exercise and vitamin D supplementation on neurotrophic factors, oxidative stress, and inflammation in AD mice, showing that treated groups—particularly the combined vitamin D and exercise group—exhibited significant increases in both BDNF and NGF (29).Furthermore, Belaya et al., evaluated the impact of long-term voluntary exercise on astrocyte modulation and BDNF expression. Behavioral assessments revealed improvements in cognition and learning, while histological and biochemical analyses indicated reduced neuronal loss, mitigated neurogenesis impairment, decreased beta-amyloid (Aβ) deposition, and attenuated inflammation. Their results demonstrated that voluntary exercise significantly increased hippocampal BDNF levels (12).

Moreover, Hashiguchi et al., reported that resistance training exerts beneficial effects by reducing neuronal damage and enhancing BDNF levels in AD models, which is consistent with the superior outcomes observed in the resistance exercise group compared to the forced swimming group in the present study (30). Similarly, Lee et al., demonstrated that obese mice injected with beta-amyloid exhibited sustained improvements in cardiopulmonary function, muscle endurance, and short-term memory following a 12-week combined aerobic and resistance training program. These beneficial effects were attributed to the reduction of beta-amyloid plaques, a critical factor in cognitive decline, and the activation of PGC-1α, FNDC5, and BDNF protein expression in the quadriceps, hippocampus, and cerebral cortex (31).

Jafarzadeh et al., demonstrated that eight weeks of resistance training significantly increased the expression of BDNF, NT3, NGF, and their respective receptors TrkA and TrkB in Wistar rats with AD (15). Similarly, Arslankiran et al., reported that both voluntary and forced/regular exercise improved cognitive function and mood impairments induced by chronic social isolation in male adolescents, which was associated with increased neuronal density in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex as well as elevated secretion of neurotrophic factors including NGF, VEGF, and BDNF (11). Belviranlı et al., demonstrated that voluntary, involuntary, and forced exercises almost equally improved behavioral impairments in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. These effects were associated with the regulation of hippocampal neurotrophic factors, including BDNF and NGF, and a reduction in oxidative stress, indicating the positive role of exercise in neuroprotection and cognitive function enhancement (32). This discrepancy may be related to differences in exercise protocols, training intensity and duration, animal models, or age of the animals. In addition, variations in the stress induced by forced exercise protocols may have influenced neurotrophic responses. Therefore, methodological differences should be considered when interpreting and comparing these findings.

Physical activity induces beneficial adaptations in the hippocampus during aging through multiple mechanisms. One key pathway involves the upregulation of neurotrophic factors such as BDNF, which serves as a critical link between muscle activity during exercise and the central nervous system, promoting neurogenesis and synaptic strengthening. Moreover, regular exercise enhances synaptic plasticity via activation of intracellular signaling cascades, including the cAMP/PKA/CREB pathway (33).

Additional beneficial effects of exercise include the prevention of hippocampal tissue degeneration as well as the reduction of inflammation and oxidative stress (34). In contrast to the present findings, Dehbozorgi et al., investigated the effects of swimming exercise combined with royal jelly on NGF and BDNF gene expression in the hippocampus of AD mice and reported that eight weeks of swimming did not significantly alter NGF and BDNF levels (17). In the study by Dehbozorgi et al., swimming exercise was performed in a standard manner without applying the overload principle or gradually increasing the exercise intensity. In contrast, the present study included voluntary, forced, and resistance exercise protocols with gradual increases in both duration and intensity, which likely provided more effective stimulation of the BDNF and NGF pathways.

Similarly, another study examining mouse model of AD subjected to eight weeks of swimming exercise, with sessions gradually increasing from 5 minutes in the first week to 60 minutes in the final week (three sessions per week), found no significant changes in hippocampal NGF and BDNF expression (17). Differences in training protocols, including exercise intensity and duration, may explain the conflicting results. Indeed, variations in the nature of exercise protocols might underlie the inconsistency of findings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings of the present study indicate that all three exercise interventions, including voluntary exercise, forced swimming, and resistance swimming, significantly increased the expression of the neurotrophic genes BDNF and NGF in mouse model of AD. Among these interventions, voluntary exercise produced the most pronounced effects, followed by resistance swimming, whereas forced swimming showed comparatively weaker effects. These results suggest that the type and nature of physical activity play a critical role in the modulation of neurotrophic signaling associated with AD. Further studies are recommended to evaluate the effects of these exercise modalities on cognitive functions, particularly spatial memory, as well as on the corresponding protein levels of BDNF and NGF. Overall, appropriately designed exercise programs, especially voluntary exercise, may be considered a beneficial non-pharmacological approach to support neural health in AD.

Study limitations

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, the relatively small sample size may limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, although changes in neurotrophic gene expression were observed, direct measurements of stress-related biomarkers, such as corticosterone or HPA axis activity, were not performed, preventing precise assessment of stress-mediated effects. Third, only male and aged mice were included, limiting applicability to females and younger populations. Future studies with larger, more diverse cohorts and direct stress assessments are warranted to further clarify these findings.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in the research, writing, or publication of this article.

Acknowledgment

There was no financial support for this study.

Funding

None

Authors’ contribution

The study was conceived and designed by all authors. Data collection and implementation of the interventions were carried out by the first author. Data analysis and interpretation of the results were performed collaboratively by the first and second authors. The initial draft of the manuscript was written by the first author, and scientific revision and final editing were conducted with the participation of all authors. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript and take responsibility for its content

References

1. Kenaan N, Alshehabi Z. A review on recent advances in Alzheimer's disease: The role of synaptic plasticity. AIMS Neuroscience. 2025; 12(2): 75-94.

2. Andrade-Guerrero J, Santiago-Balmaseda A, Jeronimo-Aguilar P, Vargas-Rodríguez I, Cadena-Suárez AR, Sánchez-Garibay C, et al. Alzheimer’s disease: an updated overview of its genetics. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023; 24(4): 1-23.

3. Bonanni R, Cariati I, Tarantino U, D’Arcangelo G, Tancredi V. Physical exercise and health: a focus on its protective role in neurodegenerative diseases. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2022; 7(2): 1-18.

4. He M, Liu Z, Lian T, Guo P, Zhang W, Huang Y, et al. Role of nerve growth factor on cognitive impairment in patients with Alzheimer's disease carrying apolipoprotein E ε4. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 2024; 30(6): 1-9.

5. Zota I, Chanoumidou K, Gravanis A, Charalampopoulos I. Stimulating myelin restoration with BDNF: a promising therapeutic approach for Alzheimer's disease. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 2024; 18: 1422130.

6. Pentz R, Iulita MF, Ducatenzeiler A, Videla L, Benejam B, Carmona Iragui M, et al. Nerve growth factor (NGF) pathway biomarkers in Down syndrome prior to and after the onset of clinical Alzheimer's disease: a paired CSF and plasma study. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2021; 17(4): 605-17.

7. Lee JJ, Sitjar PHS, Ang ET, Goh J. Exercise-induced neurogenesis through BDNF-TrkB pathway: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Translational Exercise Biomedicine. 2025; 2(1): 21-9.

8. Gholami F, Mesrabadi J, Iranpour M, Donyaei A. Exercise training alters resting brain-derived neurotrophic factor concentration in older adults: A systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Experimental Gerontology. 2025; 199: 112658.

9. Musuroglu SK, Sahin L, Annac E, Tirasci N. The effect of exercise and melatonin on social isolation stress induced BDNF downregulation and neurogenesis. Bratislava Medical Journal. 2025; 126: 1682-92.

10. Taheri A, Rohani H, Habibi A. The effect of endurance exercise training on the expression of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and nerve growth factor (NGF) genes of the cerebellum in diabetic rat. Iranian Journal of Diabetes and Obesity. 2020; 11(4): 1-8.

11. Arslankiran A, Acikgoz B, Demirtas H, Dalkiran B, Kiray A, Aksu I, et al. Effects of voluntary or involuntary exercise in adolescent male rats exposed to chronic social isolation on cognition, behavior, and neurotrophic factors. Biologia Futura. 2025; 76(1): 1-15.

12. Belaya I, Ivanova M, Sorvari A, Ilicic M, Loppi S, Koivisto H, et al. Astrocyte remodeling in the beneficial effects of long-term voluntary exercise in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2020; 17(1): 1-19.

13. Liu ZT, Ma YT, Pan ST, Xie K, Shen W, Lin SY, et al. Effects of involuntary treadmill running in combination with swimming on adult neurogenesis in an Alzheimer's mouse model. Neurochemistry International. 2022; 155: 105309.

14. Nowacka-Chmielewska M, Grabowska K, Grabowski M, Meybohm P, Burek M, Małecki A. Running from stress: neurobiological mechanisms of exercise-induced stress resilience. International Journal of Molecular Ssciences. 2022; 23(21): 13348.

15. Jafarzadeh G, Shakerian S, Farbood Y, Ghanbarzadeh M. Effects of eight weeks of resistance exercises on neurotrophins and trk receptors in alzheimer model male wistar rats. Basic and Clinical Neuroscience. 2021; 12(3): 349-59.

16. Azevedo CV, Hashiguchi D, Campos HC, Figueiredo EV, Otaviano SFS, Penitente AR, et al. The effects of resistance exercise on cognitive function, amyloidogenesis, and neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2023; 17: 1131214.

17. Dehbozorgi A, Behbudi TL, Hosseini SA, Haj RM. Effects of swimming training and royal jelly on BDNF and NGF gene expression in hippocampus tissue of rats with Alzheimer’s disease. Zahedan Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 2020; 22(2): 1-5.

18. Habibi S, Abdi A, Fazelifar S. the effect of aerobic training and resveratrol on ferroptosis in a rat model of Alzheimer's disease. The Neuroscience Journal of Shefaye Khatam. 2023; 11(4): 1-11.

19. Fathi A, Namvar Aghdash S, Fakhrpour R. Six weeks of continuous aerobic training reduces hippocampal Aβ and improves memory performance in aged AD model rats. Metabolism and Exercise. 2022: 11(2): 113-28. [Persian]

20. Ahmadi M, Vatandoust M, Hashemi Chashemi SZ. The effect of a voluntary physical activity on corticosterone and anxiety levels during and after pregnancy in mice. Journal of Practical Studies of Biosciences in Sport. 2023; 11(28): 28-38. [Persian]

21. Chali F, Desseille C, Houdebine L, Benoit E, Rouquet T, Bariohay B, et al. Long-term exercise-specific neuroprotection in spinal muscular atrophy-like mice. The Journal of Physiology. 2016; 594(7): 1931-52.

22. Xie Y, Li Z, Wang Y, Xue X, Ma W, Zhang Y, et al. Effects of moderate-versus high-intensity swimming training on inflammatory and CD4+ T cell subset profiles in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2019; 328: 60-7.

23. Alimoradi Z, Taghian F, Jalali Dehkordi K. The effect of linalool, cineole, beta bourbonin and aerobic exercises as protective approaches in mice with alzheimer's disease. Journal of Isfahan Medical School. 2023; 41(711): 148-58.

24. Peng Y, Chi R, Liu G, Tian W, Zhang J, Zhang R. Aerobic exercise regulates apoptosis through the PI3K/Akt/GSK‐3β signaling pathway to improve cognitive impairment in alzheimer’s disease mice. Neural Plasticity. 2022; 2022(1): 1500710.

25. Wan C, Shi L, Lai Y, Wu Z, Zou M, Liu Z, et al. Long-term voluntary running improves cognitive ability in developing mice by modulating the cholinergic system, antioxidant ability, and BDNF/PI3K/Akt/CREB pathway. Neuroscience Letters. 2024; 836(1): 137872.

26. Lu Y, Bu FQ, Wang F, Liu L, Zhang S, Wang G, et al. Recent advances on the molecular mechanisms of exercise-induced improvements of cognitive dysfunction. Translational Neurodegeneration. 2023; 12(1): 1-21.

27. Li WY, Gao JY, Lin SY, Pan ST, Xiao B, Ma YT, et al. Effects of involuntary and voluntary exercise in combination with Acousto-optic stimulation on adult neurogenesis in an Alzheimer's mouse model. Molecular Neurobiology. 2022; 59(5): 3254-79.

28. Wang H, Han J. The endocannabinoid system regulates the moderate exercise-induced enhancement of learning and memory in mice. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. 2020; 60(2):320-8.

29. Medhat E, Rashed L, Abdelgwad M, Aboulhoda BE, Khalifa MM, El-Din SS. Exercise enhances the effectiveness of vitamin D therapy in rats with Alzheimer’s disease: emphasis on oxidative stress and inflammation. Metabolic Brain Disease. 2020; 35(1): 111-20.

30. Hashiguchi D, Campos HC, Wuo-Silva R, Faber J, Gomes da Silva S, Coppi AA, et al. Resistance exercise decreases amyloid load and modulates inflammatory responses in the APP/PS1 mouse model for Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2020; 73(4): 1525-39.

31. Lee G, Kim Y, Jang JH, Lee C, Yoon J, Ahn N, et al. Effects of an exercise program combining aerobic and resistance training on protein expressions of neurotrophic factors in obese rats injected with beta-amyloid. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(13): 7921.

32. Belviranlı M, Okudan N. Voluntary, involuntary and forced exercises almost equally reverse behavioral impairment by regulating hippocampal neurotrophic factors and oxidative stress in experimental Alzheimer’s disease model. Behavioural Brain Research. 2019; 364: 245-55.

33. Babaei P, Azari HB. Exercise training improves memory performance in older adults: a narrative review of evidence and possible mechanisms. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2022; 15: 1-15.

34. Vints WA, Šeikinaitė J, Gökçe E, Kušleikienė S, Šarkinaite M, Valatkeviciene K, et al. Resistance exercise effects on hippocampus subfield volumes and biomarkers of neuroplasticity and neuroinflammation in older adults with low and high risk of mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. Geroscience. 2024; 46(4): 3971-91.

Consistent with our findings, Peng et al., reported that aerobic exercise activates the PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β pathway, reducing neuronal apoptosis and improving cognitive function in AD mouse models (24). This is in line with the increased BDNF expression observed in the present study, as BDNF plays a central role in PI3K/Akt pathway activation. Similarly, long-term voluntary running has been shown to enhance cognitive performance via the BDNF/PI3K/Akt/CREB signaling pathway. Based on evidence from previous studies, voluntary exercise is generally associated with lower stress and more natural psychological engagement, which can enhance the activation of neurotrophic pathways, including BDNF and NGF. Conversely, forced exercise may elicit chronic stress, leading to elevated corticosterone or cortisol levels, which can suppress the upregulation of these neurotrophic factors (25).

Recent studies have highlighted the crucial role of molecular pathways, including BDNF-TrkB and PI3K/Akt, in mediating exercise-induced improvements in cognitive deficits. Exercise generally upregulates BDNF expression, which binds to the TrkB receptor and activates multiple downstream signaling pathways, including PI3K/Akt. These pathways promote neuronal survival, enhance synaptic plasticity, and reduce inflammation, collectively contributing to improved cognitive function (26). Li et al., investigated the effects of voluntary wheel running and involuntary treadmill exercise in an AD mouse model and reported that both exercise modalities increased BDNF protein levels (27). Similarly, Wang et al., demonstrated that four weeks of moderate treadmill exercise enhanced learning and memory, accompanied by increased hippocampal BDNF production and dendritic density (28). Medhat et al., examined the combined effects of exercise and vitamin D supplementation on neurotrophic factors, oxidative stress, and inflammation in AD mice, showing that treated groups—particularly the combined vitamin D and exercise group—exhibited significant increases in both BDNF and NGF (29).Furthermore, Belaya et al., evaluated the impact of long-term voluntary exercise on astrocyte modulation and BDNF expression. Behavioral assessments revealed improvements in cognition and learning, while histological and biochemical analyses indicated reduced neuronal loss, mitigated neurogenesis impairment, decreased beta-amyloid (Aβ) deposition, and attenuated inflammation. Their results demonstrated that voluntary exercise significantly increased hippocampal BDNF levels (12).

Moreover, Hashiguchi et al., reported that resistance training exerts beneficial effects by reducing neuronal damage and enhancing BDNF levels in AD models, which is consistent with the superior outcomes observed in the resistance exercise group compared to the forced swimming group in the present study (30). Similarly, Lee et al., demonstrated that obese mice injected with beta-amyloid exhibited sustained improvements in cardiopulmonary function, muscle endurance, and short-term memory following a 12-week combined aerobic and resistance training program. These beneficial effects were attributed to the reduction of beta-amyloid plaques, a critical factor in cognitive decline, and the activation of PGC-1α, FNDC5, and BDNF protein expression in the quadriceps, hippocampus, and cerebral cortex (31).

Jafarzadeh et al., demonstrated that eight weeks of resistance training significantly increased the expression of BDNF, NT3, NGF, and their respective receptors TrkA and TrkB in Wistar rats with AD (15). Similarly, Arslankiran et al., reported that both voluntary and forced/regular exercise improved cognitive function and mood impairments induced by chronic social isolation in male adolescents, which was associated with increased neuronal density in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex as well as elevated secretion of neurotrophic factors including NGF, VEGF, and BDNF (11). Belviranlı et al., demonstrated that voluntary, involuntary, and forced exercises almost equally improved behavioral impairments in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. These effects were associated with the regulation of hippocampal neurotrophic factors, including BDNF and NGF, and a reduction in oxidative stress, indicating the positive role of exercise in neuroprotection and cognitive function enhancement (32). This discrepancy may be related to differences in exercise protocols, training intensity and duration, animal models, or age of the animals. In addition, variations in the stress induced by forced exercise protocols may have influenced neurotrophic responses. Therefore, methodological differences should be considered when interpreting and comparing these findings.

Physical activity induces beneficial adaptations in the hippocampus during aging through multiple mechanisms. One key pathway involves the upregulation of neurotrophic factors such as BDNF, which serves as a critical link between muscle activity during exercise and the central nervous system, promoting neurogenesis and synaptic strengthening. Moreover, regular exercise enhances synaptic plasticity via activation of intracellular signaling cascades, including the cAMP/PKA/CREB pathway (33).

Additional beneficial effects of exercise include the prevention of hippocampal tissue degeneration as well as the reduction of inflammation and oxidative stress (34). In contrast to the present findings, Dehbozorgi et al., investigated the effects of swimming exercise combined with royal jelly on NGF and BDNF gene expression in the hippocampus of AD mice and reported that eight weeks of swimming did not significantly alter NGF and BDNF levels (17). In the study by Dehbozorgi et al., swimming exercise was performed in a standard manner without applying the overload principle or gradually increasing the exercise intensity. In contrast, the present study included voluntary, forced, and resistance exercise protocols with gradual increases in both duration and intensity, which likely provided more effective stimulation of the BDNF and NGF pathways.

Similarly, another study examining mouse model of AD subjected to eight weeks of swimming exercise, with sessions gradually increasing from 5 minutes in the first week to 60 minutes in the final week (three sessions per week), found no significant changes in hippocampal NGF and BDNF expression (17). Differences in training protocols, including exercise intensity and duration, may explain the conflicting results. Indeed, variations in the nature of exercise protocols might underlie the inconsistency of findings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings of the present study indicate that all three exercise interventions, including voluntary exercise, forced swimming, and resistance swimming, significantly increased the expression of the neurotrophic genes BDNF and NGF in mouse model of AD. Among these interventions, voluntary exercise produced the most pronounced effects, followed by resistance swimming, whereas forced swimming showed comparatively weaker effects. These results suggest that the type and nature of physical activity play a critical role in the modulation of neurotrophic signaling associated with AD. Further studies are recommended to evaluate the effects of these exercise modalities on cognitive functions, particularly spatial memory, as well as on the corresponding protein levels of BDNF and NGF. Overall, appropriately designed exercise programs, especially voluntary exercise, may be considered a beneficial non-pharmacological approach to support neural health in AD.

Study limitations

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, the relatively small sample size may limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, although changes in neurotrophic gene expression were observed, direct measurements of stress-related biomarkers, such as corticosterone or HPA axis activity, were not performed, preventing precise assessment of stress-mediated effects. Third, only male and aged mice were included, limiting applicability to females and younger populations. Future studies with larger, more diverse cohorts and direct stress assessments are warranted to further clarify these findings.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in the research, writing, or publication of this article.

Acknowledgment

There was no financial support for this study.

Funding

None

Authors’ contribution

The study was conceived and designed by all authors. Data collection and implementation of the interventions were carried out by the first author. Data analysis and interpretation of the results were performed collaboratively by the first and second authors. The initial draft of the manuscript was written by the first author, and scientific revision and final editing were conducted with the participation of all authors. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript and take responsibility for its content

References

1. Kenaan N, Alshehabi Z. A review on recent advances in Alzheimer's disease: The role of synaptic plasticity. AIMS Neuroscience. 2025; 12(2): 75-94.

2. Andrade-Guerrero J, Santiago-Balmaseda A, Jeronimo-Aguilar P, Vargas-Rodríguez I, Cadena-Suárez AR, Sánchez-Garibay C, et al. Alzheimer’s disease: an updated overview of its genetics. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023; 24(4): 1-23.

3. Bonanni R, Cariati I, Tarantino U, D’Arcangelo G, Tancredi V. Physical exercise and health: a focus on its protective role in neurodegenerative diseases. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2022; 7(2): 1-18.

4. He M, Liu Z, Lian T, Guo P, Zhang W, Huang Y, et al. Role of nerve growth factor on cognitive impairment in patients with Alzheimer's disease carrying apolipoprotein E ε4. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 2024; 30(6): 1-9.

5. Zota I, Chanoumidou K, Gravanis A, Charalampopoulos I. Stimulating myelin restoration with BDNF: a promising therapeutic approach for Alzheimer's disease. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 2024; 18: 1422130.

6. Pentz R, Iulita MF, Ducatenzeiler A, Videla L, Benejam B, Carmona Iragui M, et al. Nerve growth factor (NGF) pathway biomarkers in Down syndrome prior to and after the onset of clinical Alzheimer's disease: a paired CSF and plasma study. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2021; 17(4): 605-17.

7. Lee JJ, Sitjar PHS, Ang ET, Goh J. Exercise-induced neurogenesis through BDNF-TrkB pathway: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Translational Exercise Biomedicine. 2025; 2(1): 21-9.

8. Gholami F, Mesrabadi J, Iranpour M, Donyaei A. Exercise training alters resting brain-derived neurotrophic factor concentration in older adults: A systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Experimental Gerontology. 2025; 199: 112658.

9. Musuroglu SK, Sahin L, Annac E, Tirasci N. The effect of exercise and melatonin on social isolation stress induced BDNF downregulation and neurogenesis. Bratislava Medical Journal. 2025; 126: 1682-92.

10. Taheri A, Rohani H, Habibi A. The effect of endurance exercise training on the expression of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and nerve growth factor (NGF) genes of the cerebellum in diabetic rat. Iranian Journal of Diabetes and Obesity. 2020; 11(4): 1-8.

11. Arslankiran A, Acikgoz B, Demirtas H, Dalkiran B, Kiray A, Aksu I, et al. Effects of voluntary or involuntary exercise in adolescent male rats exposed to chronic social isolation on cognition, behavior, and neurotrophic factors. Biologia Futura. 2025; 76(1): 1-15.

12. Belaya I, Ivanova M, Sorvari A, Ilicic M, Loppi S, Koivisto H, et al. Astrocyte remodeling in the beneficial effects of long-term voluntary exercise in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2020; 17(1): 1-19.

13. Liu ZT, Ma YT, Pan ST, Xie K, Shen W, Lin SY, et al. Effects of involuntary treadmill running in combination with swimming on adult neurogenesis in an Alzheimer's mouse model. Neurochemistry International. 2022; 155: 105309.

14. Nowacka-Chmielewska M, Grabowska K, Grabowski M, Meybohm P, Burek M, Małecki A. Running from stress: neurobiological mechanisms of exercise-induced stress resilience. International Journal of Molecular Ssciences. 2022; 23(21): 13348.

15. Jafarzadeh G, Shakerian S, Farbood Y, Ghanbarzadeh M. Effects of eight weeks of resistance exercises on neurotrophins and trk receptors in alzheimer model male wistar rats. Basic and Clinical Neuroscience. 2021; 12(3): 349-59.

16. Azevedo CV, Hashiguchi D, Campos HC, Figueiredo EV, Otaviano SFS, Penitente AR, et al. The effects of resistance exercise on cognitive function, amyloidogenesis, and neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2023; 17: 1131214.

17. Dehbozorgi A, Behbudi TL, Hosseini SA, Haj RM. Effects of swimming training and royal jelly on BDNF and NGF gene expression in hippocampus tissue of rats with Alzheimer’s disease. Zahedan Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 2020; 22(2): 1-5.

18. Habibi S, Abdi A, Fazelifar S. the effect of aerobic training and resveratrol on ferroptosis in a rat model of Alzheimer's disease. The Neuroscience Journal of Shefaye Khatam. 2023; 11(4): 1-11.

19. Fathi A, Namvar Aghdash S, Fakhrpour R. Six weeks of continuous aerobic training reduces hippocampal Aβ and improves memory performance in aged AD model rats. Metabolism and Exercise. 2022: 11(2): 113-28. [Persian]

20. Ahmadi M, Vatandoust M, Hashemi Chashemi SZ. The effect of a voluntary physical activity on corticosterone and anxiety levels during and after pregnancy in mice. Journal of Practical Studies of Biosciences in Sport. 2023; 11(28): 28-38. [Persian]

21. Chali F, Desseille C, Houdebine L, Benoit E, Rouquet T, Bariohay B, et al. Long-term exercise-specific neuroprotection in spinal muscular atrophy-like mice. The Journal of Physiology. 2016; 594(7): 1931-52.

22. Xie Y, Li Z, Wang Y, Xue X, Ma W, Zhang Y, et al. Effects of moderate-versus high-intensity swimming training on inflammatory and CD4+ T cell subset profiles in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2019; 328: 60-7.

23. Alimoradi Z, Taghian F, Jalali Dehkordi K. The effect of linalool, cineole, beta bourbonin and aerobic exercises as protective approaches in mice with alzheimer's disease. Journal of Isfahan Medical School. 2023; 41(711): 148-58.

24. Peng Y, Chi R, Liu G, Tian W, Zhang J, Zhang R. Aerobic exercise regulates apoptosis through the PI3K/Akt/GSK‐3β signaling pathway to improve cognitive impairment in alzheimer’s disease mice. Neural Plasticity. 2022; 2022(1): 1500710.

25. Wan C, Shi L, Lai Y, Wu Z, Zou M, Liu Z, et al. Long-term voluntary running improves cognitive ability in developing mice by modulating the cholinergic system, antioxidant ability, and BDNF/PI3K/Akt/CREB pathway. Neuroscience Letters. 2024; 836(1): 137872.

26. Lu Y, Bu FQ, Wang F, Liu L, Zhang S, Wang G, et al. Recent advances on the molecular mechanisms of exercise-induced improvements of cognitive dysfunction. Translational Neurodegeneration. 2023; 12(1): 1-21.

27. Li WY, Gao JY, Lin SY, Pan ST, Xiao B, Ma YT, et al. Effects of involuntary and voluntary exercise in combination with Acousto-optic stimulation on adult neurogenesis in an Alzheimer's mouse model. Molecular Neurobiology. 2022; 59(5): 3254-79.

28. Wang H, Han J. The endocannabinoid system regulates the moderate exercise-induced enhancement of learning and memory in mice. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. 2020; 60(2):320-8.

29. Medhat E, Rashed L, Abdelgwad M, Aboulhoda BE, Khalifa MM, El-Din SS. Exercise enhances the effectiveness of vitamin D therapy in rats with Alzheimer’s disease: emphasis on oxidative stress and inflammation. Metabolic Brain Disease. 2020; 35(1): 111-20.

30. Hashiguchi D, Campos HC, Wuo-Silva R, Faber J, Gomes da Silva S, Coppi AA, et al. Resistance exercise decreases amyloid load and modulates inflammatory responses in the APP/PS1 mouse model for Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2020; 73(4): 1525-39.

31. Lee G, Kim Y, Jang JH, Lee C, Yoon J, Ahn N, et al. Effects of an exercise program combining aerobic and resistance training on protein expressions of neurotrophic factors in obese rats injected with beta-amyloid. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(13): 7921.

32. Belviranlı M, Okudan N. Voluntary, involuntary and forced exercises almost equally reverse behavioral impairment by regulating hippocampal neurotrophic factors and oxidative stress in experimental Alzheimer’s disease model. Behavioural Brain Research. 2019; 364: 245-55.

33. Babaei P, Azari HB. Exercise training improves memory performance in older adults: a narrative review of evidence and possible mechanisms. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2022; 15: 1-15.

34. Vints WA, Šeikinaitė J, Gökçe E, Kušleikienė S, Šarkinaite M, Valatkeviciene K, et al. Resistance exercise effects on hippocampus subfield volumes and biomarkers of neuroplasticity and neuroinflammation in older adults with low and high risk of mild cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. Geroscience. 2024; 46(4): 3971-91.

Type of Study: Research |

Subject:

Special

Received: 2025/09/6 | Accepted: 2025/12/23 | Published: 2025/12/19

Received: 2025/09/6 | Accepted: 2025/12/23 | Published: 2025/12/19

References

1. Kenaan N, Alshehabi Z. A review on recent advances in Alzheimer's disease: The role of synaptic plasticity. AIMS Neuroscience. 2025; 12(2): 75-94.

2. Andrade-Guerrero J, Santiago-Balmaseda A, Jeronimo-Aguilar P, Vargas-Rodríguez I, Cadena-Suárez AR, Sánchez-Garibay C, et al. Alzheimer’s disease: an updated overview of its genetics. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023; 24(4): 1-23.

3. Bonanni R, Cariati I, Tarantino U, D’Arcangelo G, Tancredi V. Physical exercise and health: a focus on its protective role in neurodegenerative diseases. Journal of Functional Morphology and Kinesiology. 2022; 7(2): 1-18.

4. He M, Liu Z, Lian T, Guo P, Zhang W, Huang Y, et al. Role of nerve growth factor on cognitive impairment in patients with Alzheimer's disease carrying apolipoprotein E ε4. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 2024; 30(6): 1-9.

5. Zota I, Chanoumidou K, Gravanis A, Charalampopoulos I. Stimulating myelin restoration with BDNF: a promising therapeutic approach for Alzheimer's disease. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 2024; 18: 1422130.

6. Pentz R, Iulita MF, Ducatenzeiler A, Videla L, Benejam B, Carmona Iragui M, et al. Nerve growth factor (NGF) pathway biomarkers in Down syndrome prior to and after the onset of clinical Alzheimer's disease: a paired CSF and plasma study. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2021; 17(4): 605-17.

7. Lee JJ, Sitjar PHS, Ang ET, Goh J. Exercise-induced neurogenesis through BDNF-TrkB pathway: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Translational Exercise Biomedicine. 2025; 2(1): 21-9.

8. Gholami F, Mesrabadi J, Iranpour M, Donyaei A. Exercise training alters resting brain-derived neurotrophic factor concentration in older adults: A systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Experimental Gerontology. 2025; 199: 112658.

9. Musuroglu SK, Sahin L, Annac E, Tirasci N. The effect of exercise and melatonin on social isolation stress induced BDNF downregulation and neurogenesis. Bratislava Medical Journal. 2025; 126: 1682-92.

10. Taheri A, Rohani H, Habibi A. The effect of endurance exercise training on the expression of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and nerve growth factor (NGF) genes of the cerebellum in diabetic rat. Iranian Journal of Diabetes and Obesity. 2020; 11(4): 1-8.

11. Arslankiran A, Acikgoz B, Demirtas H, Dalkiran B, Kiray A, Aksu I, et al. Effects of voluntary or involuntary exercise in adolescent male rats exposed to chronic social isolation on cognition, behavior, and neurotrophic factors. Biologia Futura. 2025; 76(1): 1-15.

12. Belaya I, Ivanova M, Sorvari A, Ilicic M, Loppi S, Koivisto H, et al. Astrocyte remodeling in the beneficial effects of long-term voluntary exercise in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2020; 17(1): 1-19.

13. Liu ZT, Ma YT, Pan ST, Xie K, Shen W, Lin SY, et al. Effects of involuntary treadmill running in combination with swimming on adult neurogenesis in an Alzheimer's mouse model. Neurochemistry International. 2022; 155: 105309.

14. Nowacka-Chmielewska M, Grabowska K, Grabowski M, Meybohm P, Burek M, Małecki A. Running from stress: neurobiological mechanisms of exercise-induced stress resilience. International Journal of Molecular Ssciences. 2022; 23(21): 13348.

15. Jafarzadeh G, Shakerian S, Farbood Y, Ghanbarzadeh M. Effects of eight weeks of resistance exercises on neurotrophins and trk receptors in alzheimer model male wistar rats. Basic and Clinical Neuroscience. 2021; 12(3): 349-59.

16. Azevedo CV, Hashiguchi D, Campos HC, Figueiredo EV, Otaviano SFS, Penitente AR, et al. The effects of resistance exercise on cognitive function, amyloidogenesis, and neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2023; 17: 1131214.

17. Dehbozorgi A, Behbudi TL, Hosseini SA, Haj RM. Effects of swimming training and royal jelly on BDNF and NGF gene expression in hippocampus tissue of rats with Alzheimer’s disease. Zahedan Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 2020; 22(2): 1-5.

18. Habibi S, Abdi A, Fazelifar S. the effect of aerobic training and resveratrol on ferroptosis in a rat model of Alzheimer's disease. The Neuroscience Journal of Shefaye Khatam. 2023; 11(4): 1-11.

19. Fathi A, Namvar Aghdash S, Fakhrpour R. Six weeks of continuous aerobic training reduces hippocampal Aβ and improves memory performance in aged AD model rats. Metabolism and Exercise. 2022: 11(2): 113-28. [Persian]

20. Ahmadi M, Vatandoust M, Hashemi Chashemi SZ. The effect of a voluntary physical activity on corticosterone and anxiety levels during and after pregnancy in mice. Journal of Practical Studies of Biosciences in Sport. 2023; 11(28): 28-38. [Persian]

21. Chali F, Desseille C, Houdebine L, Benoit E, Rouquet T, Bariohay B, et al. Long-term exercise-specific neuroprotection in spinal muscular atrophy-like mice. The Journal of Physiology. 2016; 594(7): 1931-52.

22. Xie Y, Li Z, Wang Y, Xue X, Ma W, Zhang Y, et al. Effects of moderate-versus high-intensity swimming training on inflammatory and CD4+ T cell subset profiles in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2019; 328: 60-7.

23. Alimoradi Z, Taghian F, Jalali Dehkordi K. The effect of linalool, cineole, beta bourbonin and aerobic exercises as protective approaches in mice with alzheimer's disease. Journal of Isfahan Medical School. 2023; 41(711): 148-58.

24. Peng Y, Chi R, Liu G, Tian W, Zhang J, Zhang R. Aerobic exercise regulates apoptosis through the PI3K/Akt/GSK‐3β signaling pathway to improve cognitive impairment in alzheimer’s disease mice. Neural Plasticity. 2022; 2022(1): 1500710.

25. Wan C, Shi L, Lai Y, Wu Z, Zou M, Liu Z, et al. Long-term voluntary running improves cognitive ability in developing mice by modulating the cholinergic system, antioxidant ability, and BDNF/PI3K/Akt/CREB pathway. Neuroscience Letters. 2024; 836(1): 137872.

26. Lu Y, Bu FQ, Wang F, Liu L, Zhang S, Wang G, et al. Recent advances on the molecular mechanisms of exercise-induced improvements of cognitive dysfunction. Translational Neurodegeneration. 2023; 12(1): 1-21.

27. Li WY, Gao JY, Lin SY, Pan ST, Xiao B, Ma YT, et al. Effects of involuntary and voluntary exercise in combination with Acousto-optic stimulation on adult neurogenesis in an Alzheimer's mouse model. Molecular Neurobiology. 2022; 59(5): 3254-79.

28. Wang H, Han J. The endocannabinoid system regulates the moderate exercise-induced enhancement of learning and memory in mice. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. 2020; 60(2):320-8.

29. Medhat E, Rashed L, Abdelgwad M, Aboulhoda BE, Khalifa MM, El-Din SS. Exercise enhances the effectiveness of vitamin D therapy in rats with Alzheimer’s disease: emphasis on oxidative stress and inflammation. Metabolic Brain Disease. 2020; 35(1): 111-20.

30. Hashiguchi D, Campos HC, Wuo-Silva R, Faber J, Gomes da Silva S, Coppi AA, et al. Resistance exercise decreases amyloid load and modulates inflammatory responses in the APP/PS1 mouse model for Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2020; 73(4): 1525-39.

31. Lee G, Kim Y, Jang JH, Lee C, Yoon J, Ahn N, et al. Effects of an exercise program combining aerobic and resistance training on protein expressions of neurotrophic factors in obese rats injected with beta-amyloid. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(13): 7921.

32. Belviranlı M, Okudan N. Voluntary, involuntary and forced exercises almost equally reverse behavioral impairment by regulating hippocampal neurotrophic factors and oxidative stress in experimental Alzheimer’s disease model. Behavioural Brain Research. 2019; 364: 245-55.