Volume 11, Issue 2 (December 2025)

Elderly Health Journal 2025, 11(2): 118-126 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Qorbanalipour M, Mahjoub M. Presenting a Structural Model of Psychological Health of the Elderly Based on Loneliness, Death Thoughts, and Rumination: Testing the Mediating Role of Spiritual Intelligence. Elderly Health Journal 2025; 11 (2) :118-126

URL: http://ehj.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-363-en.html

URL: http://ehj.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-363-en.html

Department of Psychology, Khoy Branch, Islamic Azad University, Khoy, Iran , masoudqorbanalipour@gmail.com

Full-Text [PDF 475 kb]

(22 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (36 Views)

Full-Text: (3 Views)

Presenting a Structural Model of Psychological Health of the Elderly Based on Loneliness, Death Thoughts, and Rumination: Testing the Mediating Role of Spiritual Intelligence

Masoud Qorbanalipour 1* , Mahdiyeh Mahjoub 1

* Corresponding Author: Department of Psychology, Khoy Branch, Islamic Azad University, Khoy, Iran. Tel: +98 9141633787, Email address: masoudqorbanalipour@gmail.com

Article history

Received 1 Oct 2025

Accepted 13 Dec 2025

A B S T R A C T

Masoud Qorbanalipour 1*

- Department of Psychology, Khoy Branch, Islamic Azad University, Khoy, Iran

* Corresponding Author: Department of Psychology, Khoy Branch, Islamic Azad University, Khoy, Iran. Tel: +98 9141633787, Email address: masoudqorbanalipour@gmail.com

Article history

Received 1 Oct 2025

Accepted 13 Dec 2025

A B S T R A C T

Introduction: The present study aimed to propose a structural model of psychological well-being among older adults based on the components of loneliness, death thought, and rumination, with a focus on the mediating role of spiritual intelligence.

Methods: This research employed a descriptive, quantitative, and correlational design using structural equation modeling. The statistical population included all older adults in the city of Khoy in 2025, from which 200 participants were selected through purposive sampling. Data were collected using the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3), Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Scale – Short Form (RPWB-SF), Death Thought Questionnaire (DTQ), Ruminative Response Scale (RRS), Spiritual Intelligence Self-Report Inventory (SISRI). Data analysis was conducted through structural equation modeling and bootstrapping techniques using SmartPLS software.

Results: The findings indicated that loneliness (β = -0.40), rumination (β = -0.38), and death thought (β = -0.30) had significant negative effects on psychological well-being in older adults. Conversely, spiritual intelligence (β = 0.50) exerted both direct and indirect positive effects by mitigating the negative impacts of loneliness (β = -0.10), rumination (β = -0.13), and death thought (β = -0.11) on psychological well-being.

Conclusion: These results highlight the protective role of spiritual intelligence against factors that threaten psychological well-being in older adults. Overall, the findings suggest that strengthening spiritual intelligence may serve as an effective strategy to reduce the adverse effects of loneliness, death thought, and rumination, thereby enhancing psychological well-being in this population.

Keywords: Loneliness, Psychological Health, Aged, Rumination, Spiritual Intelligence

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits copy and redistribute the material just in noncommercial usages, provided the original work is properly cite.

Methods: This research employed a descriptive, quantitative, and correlational design using structural equation modeling. The statistical population included all older adults in the city of Khoy in 2025, from which 200 participants were selected through purposive sampling. Data were collected using the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3), Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Scale – Short Form (RPWB-SF), Death Thought Questionnaire (DTQ), Ruminative Response Scale (RRS), Spiritual Intelligence Self-Report Inventory (SISRI). Data analysis was conducted through structural equation modeling and bootstrapping techniques using SmartPLS software.

Results: The findings indicated that loneliness (β = -0.40), rumination (β = -0.38), and death thought (β = -0.30) had significant negative effects on psychological well-being in older adults. Conversely, spiritual intelligence (β = 0.50) exerted both direct and indirect positive effects by mitigating the negative impacts of loneliness (β = -0.10), rumination (β = -0.13), and death thought (β = -0.11) on psychological well-being.

Conclusion: These results highlight the protective role of spiritual intelligence against factors that threaten psychological well-being in older adults. Overall, the findings suggest that strengthening spiritual intelligence may serve as an effective strategy to reduce the adverse effects of loneliness, death thought, and rumination, thereby enhancing psychological well-being in this population.

Keywords: Loneliness, Psychological Health, Aged, Rumination, Spiritual Intelligence

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits copy and redistribute the material just in noncommercial usages, provided the original work is properly cite.

Introduction

Psychological health in older adults is as important as their physical health. Psychological health refers to a state of mental well-being in which an individual is aware of their own abilities, can cope with the stresses of life, and is able to participate in social activities (1, 2). This concept is related to factors such as self-awareness, life satisfaction, social relationships, and the ability to cope with difficulties (3). Older adults with good psychological health are able to maintain positive social relationships, manage stress, and achieve life goals (4). In other words, psychological health is considered a key component of quality of life in older adults, influencing their ability to cope with the various challenges of aging. Among older individuals, psychological problems such as depression, anxiety, and stress can significantly affect their mental well-being. These problems are often caused by factors such as retirement, loss of loved ones, chronic illnesses, and economic difficulties (5). Research has shown that reduced quality of life and weakened social connections can lead to a decline in psychological health among older adults (6, 7). In particular, those who experience social isolation are usually at greater risk of developing mental health problems (8, 9). Therefore, promoting psychological health in this age group can have substantial positive effects on their quality of life and social well-being (10).

One of the problems that older adults face due to physical and sometimes psychological conditions is the feeling of loneliness (11). Loneliness refers to a psychological state in which an individual experiences social isolation and a sense of disconnection from others. This condition can significantly affect a person’s mental health (12, 13). Various studies have shown that loneliness is associated with an increased risk of developing mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, and stress (14). Lonely individuals are more likely to experience sleep problems, reduced quality of life, and depressive symptoms. Loneliness can also weaken the immune system and lead to the onset of physical illnesses (15). Moreover, research indicates that lonely individuals often face greater social and communication difficulties, which in turn continuously exacerbate their psychological problems (16, 17). Older adults, due to retirement, reduced social activities, or the loss of loved ones, are more vulnerable to feelings of loneliness compared to other age groups, which can have more detrimental effects on their mental health (18, 19). Research has shown that loneliness among the elderly can significantly exacerbate depression and anxiety (20, 21).

Death thought, defined as awareness of and reflection on death, also has a profound impact on individuals’ psychological health (22). Various studies have indicated that such thinking can act both as a stressor and as a stimulus for personal growth (23), thereby influencing mental well-being. Death thought refers to the cognitive process in which individuals contemplate their own mortality and its consequences. This may include worries, fears, or even philosophical reflections on the meaning of life and death (24, 25). Some studies have shown that persistent death-related thoughts may lead to heightened anxiety and depression, particularly among individuals with poor coping skills (26). On the other hand, reflection on death can also foster personal and spiritual growth. Some people, by contemplating death, come to appreciate life values more deeply and form stronger connections with others (27). Those who are able to accept death and its limitations often demonstrate better stress management and coping skills when facing life’s challenges (28). Continuous mental preoccupation with death, however, is often associated with rumination on death (29). Therefore, paying attention to the role and significance of rumination in psychological health is also of critical importance.

Rumination refers to the repetitive and excessive focus on particular thoughts, events, or issues, which may lead to heightened anxiety and psychological distress (30). This phenomenon is generally considered a maladaptive coping mechanism that individuals experience involuntarily (31, 32). People who engage in rumination may become trapped in persistent negative thoughts that they cannot dismiss, even when such thoughts are unhelpful in solving problems (33). Rumination is often associated with psychological disorders such as depression and anxiety (34). The link between rumination and psychological health is particularly significant among individuals suffering from anxiety and depression. Some studies indicate that rumination can intensify symptoms of depression and anxiety, as this mental process prevents individuals from disengaging from negative thoughts and focusing on problem-solving (35, 36). Moreover, this style of thinking can negatively affect psychological health because it traps individuals in a vicious cycle of negative thoughts, which in turn reinforces psychological symptoms (37). Studies suggest that individuals prone to rumination are more vulnerable to mental health problems such as depression and anxiety, as they lack the ability to effectively process and regulate negative emotions and tend to rely on maladaptive coping mechanisms (38). Consequently, rumination not only contributes to the development of psychological problems but also complicates the therapeutic process and recovery of mental health.

Spiritual intelligence is defined as an individual’s ability to draw upon spiritual resources and values in order to achieve inner integration and assign meaning to life experiences (39). A wide range of studies consistently demonstrate that spiritual intelligence has a direct and positive impact on psychological health and functions as a strong protective factor. Specifically, it not only directly enhances psychological well-being but also strengthens an individual’s capacity to effectively utilize emotional intelligence (40, 41). Empirical studies have further confirmed the effectiveness of spiritual intelligence training in improving indicators of mental health (42). On the other hand, research evidence indicates that rumination and persistent thoughts about death can undermine psychological health by creating a cycle of negative thinking. In this context, spiritual intelligence, as a cognitive–existential capacity, can play a protective role and moderate the impact of these negative factors on mental well-being. Findings suggest that spiritual intelligence is associated with reduced rumination and greater ability to reappraise negative thoughts, thereby serving as an internal regulatory factor (43). In other words, individuals with higher levels of spiritual intelligence are more capable of assigning meaning to unpleasant experiences, accepting the reality of death, and employing more adaptive coping strategies for stress management (44). This dual effect both mitigates the negative influence of rumination and death-related thoughts on psychological health and enhances one’s capacity to maintain well-being. Several studies have shown that spiritual intelligence is not only directly associated with psychological health indicators such as reduced anxiety, depression, and stress, but also indirectly contributes to improved mental well-being by reducing rumination and moderating death anxiety (45, 46). Therefore, it may be assumed that spiritual intelligence serves as a mediating factor between rumination, death thought, and psychological health, alleviating some of the negative effects of these factors through its existential and regulatory mechanisms.

Considering all the factors discussed, it can be concluded that psychological health in older adults arises from a complex interaction between the unique challenges of this stage of life and individuals’ internal resources. Loneliness and persistent death-related thoughts, as two major stressors, seriously threaten mental health by triggering maladaptive patterns of rumination. This vicious cycle of repetitive negative thinking plays a substantial role in the onset and exacerbation of disorders such as depression, anxiety, and stress.

In this context, spiritual intelligence, as a powerful inner resource, functions as a pivotal mediating factor. Spiritual intelligence not only has a direct and positive effect on psychological well-being but also operates indirectly by counteracting maladaptive mechanisms. Individuals with higher levels of spiritual intelligence, through their capacity to assign meaning to experiences, accept existential realities, and demonstrate greater cognitive flexibility, are able to interpret such challenges within a broader and more manageable framework. This process reduces the emotional burden of negative thoughts and protects individuals from becoming trapped in destructive cycles of rumination.

Thus, the pathway can be described as follows: loneliness and death-related thoughts increase the tendency toward rumination, which, in the absence of sufficient coping resources, leads to diminished psychological health. However, spiritual intelligence, acting as a protective buffer, moderates this negative pathway and, by providing insight and adaptive strategies, helps maintain psychological well-being even in the face of the inevitable challenges of aging. Accordingly, the present study seeks to address the following question: Can spiritual intelligence, as a mediating mechanism, moderate the relationship between aging-related stressors (such as loneliness and death thought) and psychological health?

Methods

Study design and participants

This study was fundamental in purpose and employed a descriptive-correlational design, with data analysis conducted using structural equation modeling (SEM). The statistical population included all older adults aged over 60 years residing in Khoy, Iran, and participants were recruited through purposive (non-random) sampling. To this end, with the cooperation of local health centers, community health houses, nursing homes, neighborhood Basij bases, and municipal social service centers, a list of accessible older adults was prepared. Individuals who met the inclusion criteria—being aged 60 years or older, having permanent residence in the county, possessing basic literacy skills, and providing informed consent—were invited to participate.

Data were collected through in-person visits to the aforementioned centers as well as participants’ homes. After explaining the purpose of the study and obtaining informed consent, questionnaires were distributed. In cases where participants were unable to complete the questionnaires independently, trained researchers or assistants administered the questionnaires in an interview format. According to Kline (47) for complex SEM analyses, a minimum sample size of 200 is required. Given the four independent variables (loneliness, death thought, rumination, and spiritual intelligence) and one dependent variable (psychological health), with an estimated 15–20 observed indicators, the rule of at least 10 participants per observed variable was applied, resulting in a minimum required sample size of 200. Sampling was conducted accordingly to ensure that this number of older adults from Khoy took part in the study.

Participants were older adults over the age of 60 who had relative cognitive and physical health and the ability to read, understand, and respond to the questionnaires. Inclusion criteria consisted of informed consent, absence of severe psychiatric disorders, and basic literacy. Exclusion criteria included, refusal to cooperate, or invalid responses.

Measures

Loneliness Scale (UCLA) (Version 3) – 1980: The (UCLA) was developed by Russell and colleagues in 1980 and consists of 20 items rated on a four-point Likert scale (1 to 4) (48). The questionnaire includes 10 negatively worded and 10 positively worded items. The total score ranges from 20 to 80, with a mean score of 50. Scores above the mean indicate greater severity of loneliness. The reliability of the revised version of the scale was reported as 0.78. Test–retest reliability, reported by Russell, et al., (48), was 0.89. In the study by Larijani and Moslehi (49), the reliability coefficient was reported as 0.89.

Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Scale – Short Form (RPWB-SF) - 2002: The RPWB-SF was originally developed by Ryff (50) and later revised in 2002. The short form, derived from the original 120-item version, consists of 18 items that assess six core dimensions of psychological well-being: autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance. Items are scored on a six-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 to 6), with higher scores indicating higher levels of psychological well-being and lower scores reflecting lower levels. Ryff and Singer (51) reported correlation coefficients ranging from 0.70 to 0.89, indicating good convergent validity. In Iran, Vafanoush et al., (52) examined the reliability of this scale using Cronbach’s alpha, reporting coefficients between 0.72 and 0.76 for the subscales, with an overall alpha of 0.71. Furthermore, confirmatory factor analysis supported the adequacy of the six-factor structure of the scale.

Death Thought Questionnaire (DTQ) - 1970: The DTQ was developed by Templer (53). This instrument consists of 17 items and assesses various aspects of an individual’s attitudes toward death. The scale includes several subcomponents, such as fear of death, which measures the intensity of worries and anxieties related to death; negative thoughts about death, which reflect negative attitudes and their psychological consequences for the individual’s life; and the perceived impact of death on life, which examines the extent to which individuals believe death influences their life course and decision-making processes. The items are scored using a Likert-type scale, with higher scores indicating greater intensity of death-related cognitions and concerns. Previous studies have demonstrated satisfactory reliability and validity for this instrument (54). In Iran, Sharif Nia et al., (55) reported Cronbach’s alpha coefficients above 0.80 for the original version, and construct validity has been confirmed in various studies.

Ruminative Response Scale (RRS) - 1991: The RRS was developed by Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow (56) to assess ruminative thinking. This scale consists of 22 items rated on a four-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 to 4). It includes three subcomponents: reflection, brooding, and depression-related rumination. Based on the total score, levels of rumination can be categorized as follows: scores between 22 and 33 indicate low rumination, scores between 33 and 55 reflect moderate rumination, and scores above 55 indicate high rumination. The psychometric properties of the RRS have been examined and supported by Treynor et al., (57). In Iran, Babaahmadi Milani et al., (58) reported a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.88, confirming satisfactory internal consistency of the scale.

Spiritual Intelligence Self-Report Inventory (SISRI) - 2008: SISRI was developed by King (2008) to assess spiritual intelligence across four dimensions: critical existential thinking, personal meaning production, transcendental awareness, and conscious state expansion (59). The instrument consists of 24 items rated on a five-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 to 4). Higher scores indicate higher levels of spiritual intelligence. Previous studies have demonstrated satisfactory reliability and validity of the SISRI. In Iran, Raghib et al. reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88, with face and content validity confirmed by psychology experts. Convergent validity was also supported through a correlation of 0.66 with the Spiritual Experience Questionnaire. Furthermore, exploratory and first-order confirmatory factor analyses confirmed the stability and appropriateness of its four-factor structure. Therefore, the SISRI can be considered a reliable and valid instrument for measuring spiritual intelligence in research and educational contexts, including university settings (60).

Statistical analysis

For data analysis, descriptive statistics including frequency, percentage, mean, standard deviation, and standard error were employed. For inferential statistics, Pearson correlation coefficient, multiple regression analysis, and SEM were conducted using SPSS-29 and Smart-PLS-3.

Ethical considerations

All ethical principles were observed in this research, including obtaining informed consent from participants, ensuring confidentiality and privacy, guaranteeing that no harm would occur to participants, and allowing them the right to withdraw at any stage. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, under the ethical approval code IR.IAU.URIMA.REC.1404.064. Data were used solely for scientific purposes, and psychological support was provided to participants when necessary. General feedback on the study results was made available upon request.

Results

In this study, most participants were women (61%). Less than half were married, while the remainder were single, widowed, or divorced, which may relate to experiences of loneliness. The largest age group was 66–70 years (36%), indicating that most participants were in early late adulthood. the demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Based on the statistical analyses conducted, the assumptions necessary for SEM in the present study were thoroughly examined and confirmed. First, the results of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test indicated that the distributions of all primary study variables did not significantly deviate from normality. To assess multicollinearity, Tolerance and Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) indices were calculated and are reported in the corresponding table. All Tolerance values exceeded 0.38, and all VIF values were below 2, indicating no severe multicollinearity among the predictor variables. This suggests that each variable retains its independent contribution to the model, and regression or structural analyses are not biased by multicollinearity.

Furthermore, the assumption of independence of residuals was tested. Correlation coefficients among residuals ranged from 0.023 to 0.042, with associated p-values between 0.068 and 0.112, all above the 0.05 threshold. These results confirm the absence of significant correlations among residuals, thereby supporting the independence assumption. Accordingly, the statistical model can be considered valid, and the estimates obtained are unbiased and reliable.

Construct reliability and validity were also examined. Cronbach’s alpha values for all variables exceeded 0.80, ranging from 0.80 to 0.88, indicating satisfactory internal consistency. Rho values ranged from 0.71 to 0.87, and composite reliability (CR) values were above 0.70 (0.80–0.83), further supporting adequate construct reliability. The average variance extracted (AVE) for all constructs was above 0.50, with the “death thought” variable reaching the borderline value of 0.50, which is still considered acceptable.

Overall, the results of the statistical assumption checks, along with the reliability and validity indices, indicate that the study data are of high quality, and the instruments employed are both valid and reliable. Therefore, the proposed structural model, based on the variables of loneliness, death thought, rumination, and spiritual intelligence, is methodologically and empirically supported, and the obtained results can be considered trustworthy and interpretable.

Based on the results presented in Table 2, the structural model demonstrated satisfactory fit indices. The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) was 0.043, below the recommended threshold of 0.08, indicating an excellent fit of the model to the empirical data. Additionally, the Normed Fit Index (NFI) was 0.962, exceeding the acceptable threshold of 0.90, suggesting that the proposed model provides a superior explanation of the data compared to the baseline model. Overall, these indices indicate that the structural model has an adequate fit, supporting the validity and reliability of the obtained results.

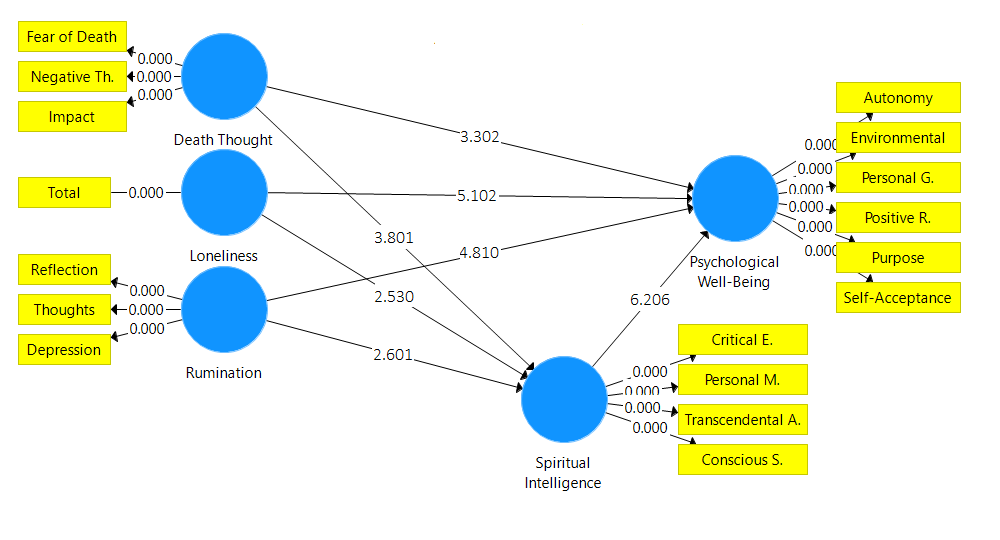

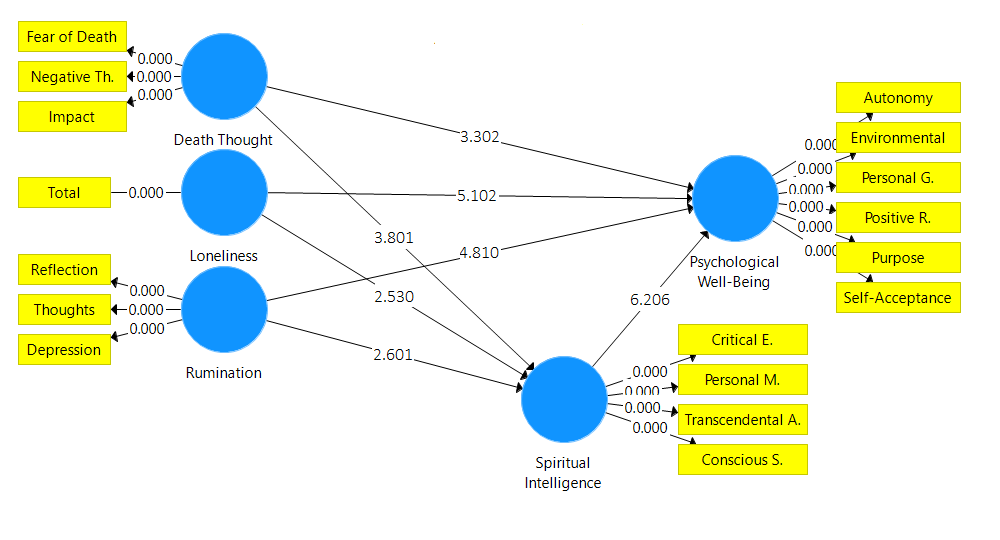

The results of the structural model (Table 3 & Figure 1) indicate that all direct and indirect paths were statistically significant. Psychological well-being had a significant positive effect on spiritual intelligence (β = 0.50, p < 0.001) and a significant negative effect on loneliness (β = -0.40, p < 0.001), rumination (β = -0.38, p < 0.001), and death-related thoughts (β = -0.30, p = 0.001). In turn, spiritual intelligence significantly reduced loneliness (β = -0.20, p = 0.011), rumination (β = -0.25, p = 0.009), and death-related thoughts (β = -0.35, p < 0.001). All indirect effects of psychological well-being on these outcomes through spiritual intelligence were also significant, highlighting the mediating role of spiritual intelligence in attenuating the negative impact of low psychological well-being on loneliness, rumination, and death-related thoughts. Overall, the model confirms both the direct and mediating influences of spiritual intelligence on key psychological outcomes among older adults.

One of the problems that older adults face due to physical and sometimes psychological conditions is the feeling of loneliness (11). Loneliness refers to a psychological state in which an individual experiences social isolation and a sense of disconnection from others. This condition can significantly affect a person’s mental health (12, 13). Various studies have shown that loneliness is associated with an increased risk of developing mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, and stress (14). Lonely individuals are more likely to experience sleep problems, reduced quality of life, and depressive symptoms. Loneliness can also weaken the immune system and lead to the onset of physical illnesses (15). Moreover, research indicates that lonely individuals often face greater social and communication difficulties, which in turn continuously exacerbate their psychological problems (16, 17). Older adults, due to retirement, reduced social activities, or the loss of loved ones, are more vulnerable to feelings of loneliness compared to other age groups, which can have more detrimental effects on their mental health (18, 19). Research has shown that loneliness among the elderly can significantly exacerbate depression and anxiety (20, 21).

Death thought, defined as awareness of and reflection on death, also has a profound impact on individuals’ psychological health (22). Various studies have indicated that such thinking can act both as a stressor and as a stimulus for personal growth (23), thereby influencing mental well-being. Death thought refers to the cognitive process in which individuals contemplate their own mortality and its consequences. This may include worries, fears, or even philosophical reflections on the meaning of life and death (24, 25). Some studies have shown that persistent death-related thoughts may lead to heightened anxiety and depression, particularly among individuals with poor coping skills (26). On the other hand, reflection on death can also foster personal and spiritual growth. Some people, by contemplating death, come to appreciate life values more deeply and form stronger connections with others (27). Those who are able to accept death and its limitations often demonstrate better stress management and coping skills when facing life’s challenges (28). Continuous mental preoccupation with death, however, is often associated with rumination on death (29). Therefore, paying attention to the role and significance of rumination in psychological health is also of critical importance.

Rumination refers to the repetitive and excessive focus on particular thoughts, events, or issues, which may lead to heightened anxiety and psychological distress (30). This phenomenon is generally considered a maladaptive coping mechanism that individuals experience involuntarily (31, 32). People who engage in rumination may become trapped in persistent negative thoughts that they cannot dismiss, even when such thoughts are unhelpful in solving problems (33). Rumination is often associated with psychological disorders such as depression and anxiety (34). The link between rumination and psychological health is particularly significant among individuals suffering from anxiety and depression. Some studies indicate that rumination can intensify symptoms of depression and anxiety, as this mental process prevents individuals from disengaging from negative thoughts and focusing on problem-solving (35, 36). Moreover, this style of thinking can negatively affect psychological health because it traps individuals in a vicious cycle of negative thoughts, which in turn reinforces psychological symptoms (37). Studies suggest that individuals prone to rumination are more vulnerable to mental health problems such as depression and anxiety, as they lack the ability to effectively process and regulate negative emotions and tend to rely on maladaptive coping mechanisms (38). Consequently, rumination not only contributes to the development of psychological problems but also complicates the therapeutic process and recovery of mental health.

Spiritual intelligence is defined as an individual’s ability to draw upon spiritual resources and values in order to achieve inner integration and assign meaning to life experiences (39). A wide range of studies consistently demonstrate that spiritual intelligence has a direct and positive impact on psychological health and functions as a strong protective factor. Specifically, it not only directly enhances psychological well-being but also strengthens an individual’s capacity to effectively utilize emotional intelligence (40, 41). Empirical studies have further confirmed the effectiveness of spiritual intelligence training in improving indicators of mental health (42). On the other hand, research evidence indicates that rumination and persistent thoughts about death can undermine psychological health by creating a cycle of negative thinking. In this context, spiritual intelligence, as a cognitive–existential capacity, can play a protective role and moderate the impact of these negative factors on mental well-being. Findings suggest that spiritual intelligence is associated with reduced rumination and greater ability to reappraise negative thoughts, thereby serving as an internal regulatory factor (43). In other words, individuals with higher levels of spiritual intelligence are more capable of assigning meaning to unpleasant experiences, accepting the reality of death, and employing more adaptive coping strategies for stress management (44). This dual effect both mitigates the negative influence of rumination and death-related thoughts on psychological health and enhances one’s capacity to maintain well-being. Several studies have shown that spiritual intelligence is not only directly associated with psychological health indicators such as reduced anxiety, depression, and stress, but also indirectly contributes to improved mental well-being by reducing rumination and moderating death anxiety (45, 46). Therefore, it may be assumed that spiritual intelligence serves as a mediating factor between rumination, death thought, and psychological health, alleviating some of the negative effects of these factors through its existential and regulatory mechanisms.

Considering all the factors discussed, it can be concluded that psychological health in older adults arises from a complex interaction between the unique challenges of this stage of life and individuals’ internal resources. Loneliness and persistent death-related thoughts, as two major stressors, seriously threaten mental health by triggering maladaptive patterns of rumination. This vicious cycle of repetitive negative thinking plays a substantial role in the onset and exacerbation of disorders such as depression, anxiety, and stress.

In this context, spiritual intelligence, as a powerful inner resource, functions as a pivotal mediating factor. Spiritual intelligence not only has a direct and positive effect on psychological well-being but also operates indirectly by counteracting maladaptive mechanisms. Individuals with higher levels of spiritual intelligence, through their capacity to assign meaning to experiences, accept existential realities, and demonstrate greater cognitive flexibility, are able to interpret such challenges within a broader and more manageable framework. This process reduces the emotional burden of negative thoughts and protects individuals from becoming trapped in destructive cycles of rumination.

Thus, the pathway can be described as follows: loneliness and death-related thoughts increase the tendency toward rumination, which, in the absence of sufficient coping resources, leads to diminished psychological health. However, spiritual intelligence, acting as a protective buffer, moderates this negative pathway and, by providing insight and adaptive strategies, helps maintain psychological well-being even in the face of the inevitable challenges of aging. Accordingly, the present study seeks to address the following question: Can spiritual intelligence, as a mediating mechanism, moderate the relationship between aging-related stressors (such as loneliness and death thought) and psychological health?

Methods

Study design and participants

This study was fundamental in purpose and employed a descriptive-correlational design, with data analysis conducted using structural equation modeling (SEM). The statistical population included all older adults aged over 60 years residing in Khoy, Iran, and participants were recruited through purposive (non-random) sampling. To this end, with the cooperation of local health centers, community health houses, nursing homes, neighborhood Basij bases, and municipal social service centers, a list of accessible older adults was prepared. Individuals who met the inclusion criteria—being aged 60 years or older, having permanent residence in the county, possessing basic literacy skills, and providing informed consent—were invited to participate.

Data were collected through in-person visits to the aforementioned centers as well as participants’ homes. After explaining the purpose of the study and obtaining informed consent, questionnaires were distributed. In cases where participants were unable to complete the questionnaires independently, trained researchers or assistants administered the questionnaires in an interview format. According to Kline (47) for complex SEM analyses, a minimum sample size of 200 is required. Given the four independent variables (loneliness, death thought, rumination, and spiritual intelligence) and one dependent variable (psychological health), with an estimated 15–20 observed indicators, the rule of at least 10 participants per observed variable was applied, resulting in a minimum required sample size of 200. Sampling was conducted accordingly to ensure that this number of older adults from Khoy took part in the study.

Participants were older adults over the age of 60 who had relative cognitive and physical health and the ability to read, understand, and respond to the questionnaires. Inclusion criteria consisted of informed consent, absence of severe psychiatric disorders, and basic literacy. Exclusion criteria included, refusal to cooperate, or invalid responses.

Measures

Loneliness Scale (UCLA) (Version 3) – 1980: The (UCLA) was developed by Russell and colleagues in 1980 and consists of 20 items rated on a four-point Likert scale (1 to 4) (48). The questionnaire includes 10 negatively worded and 10 positively worded items. The total score ranges from 20 to 80, with a mean score of 50. Scores above the mean indicate greater severity of loneliness. The reliability of the revised version of the scale was reported as 0.78. Test–retest reliability, reported by Russell, et al., (48), was 0.89. In the study by Larijani and Moslehi (49), the reliability coefficient was reported as 0.89.

Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Scale – Short Form (RPWB-SF) - 2002: The RPWB-SF was originally developed by Ryff (50) and later revised in 2002. The short form, derived from the original 120-item version, consists of 18 items that assess six core dimensions of psychological well-being: autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance. Items are scored on a six-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 to 6), with higher scores indicating higher levels of psychological well-being and lower scores reflecting lower levels. Ryff and Singer (51) reported correlation coefficients ranging from 0.70 to 0.89, indicating good convergent validity. In Iran, Vafanoush et al., (52) examined the reliability of this scale using Cronbach’s alpha, reporting coefficients between 0.72 and 0.76 for the subscales, with an overall alpha of 0.71. Furthermore, confirmatory factor analysis supported the adequacy of the six-factor structure of the scale.

Death Thought Questionnaire (DTQ) - 1970: The DTQ was developed by Templer (53). This instrument consists of 17 items and assesses various aspects of an individual’s attitudes toward death. The scale includes several subcomponents, such as fear of death, which measures the intensity of worries and anxieties related to death; negative thoughts about death, which reflect negative attitudes and their psychological consequences for the individual’s life; and the perceived impact of death on life, which examines the extent to which individuals believe death influences their life course and decision-making processes. The items are scored using a Likert-type scale, with higher scores indicating greater intensity of death-related cognitions and concerns. Previous studies have demonstrated satisfactory reliability and validity for this instrument (54). In Iran, Sharif Nia et al., (55) reported Cronbach’s alpha coefficients above 0.80 for the original version, and construct validity has been confirmed in various studies.

Ruminative Response Scale (RRS) - 1991: The RRS was developed by Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow (56) to assess ruminative thinking. This scale consists of 22 items rated on a four-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 to 4). It includes three subcomponents: reflection, brooding, and depression-related rumination. Based on the total score, levels of rumination can be categorized as follows: scores between 22 and 33 indicate low rumination, scores between 33 and 55 reflect moderate rumination, and scores above 55 indicate high rumination. The psychometric properties of the RRS have been examined and supported by Treynor et al., (57). In Iran, Babaahmadi Milani et al., (58) reported a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.88, confirming satisfactory internal consistency of the scale.

Spiritual Intelligence Self-Report Inventory (SISRI) - 2008: SISRI was developed by King (2008) to assess spiritual intelligence across four dimensions: critical existential thinking, personal meaning production, transcendental awareness, and conscious state expansion (59). The instrument consists of 24 items rated on a five-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 to 4). Higher scores indicate higher levels of spiritual intelligence. Previous studies have demonstrated satisfactory reliability and validity of the SISRI. In Iran, Raghib et al. reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88, with face and content validity confirmed by psychology experts. Convergent validity was also supported through a correlation of 0.66 with the Spiritual Experience Questionnaire. Furthermore, exploratory and first-order confirmatory factor analyses confirmed the stability and appropriateness of its four-factor structure. Therefore, the SISRI can be considered a reliable and valid instrument for measuring spiritual intelligence in research and educational contexts, including university settings (60).

Statistical analysis

For data analysis, descriptive statistics including frequency, percentage, mean, standard deviation, and standard error were employed. For inferential statistics, Pearson correlation coefficient, multiple regression analysis, and SEM were conducted using SPSS-29 and Smart-PLS-3.

Ethical considerations

All ethical principles were observed in this research, including obtaining informed consent from participants, ensuring confidentiality and privacy, guaranteeing that no harm would occur to participants, and allowing them the right to withdraw at any stage. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University, under the ethical approval code IR.IAU.URIMA.REC.1404.064. Data were used solely for scientific purposes, and psychological support was provided to participants when necessary. General feedback on the study results was made available upon request.

Results

In this study, most participants were women (61%). Less than half were married, while the remainder were single, widowed, or divorced, which may relate to experiences of loneliness. The largest age group was 66–70 years (36%), indicating that most participants were in early late adulthood. the demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Based on the statistical analyses conducted, the assumptions necessary for SEM in the present study were thoroughly examined and confirmed. First, the results of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test indicated that the distributions of all primary study variables did not significantly deviate from normality. To assess multicollinearity, Tolerance and Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) indices were calculated and are reported in the corresponding table. All Tolerance values exceeded 0.38, and all VIF values were below 2, indicating no severe multicollinearity among the predictor variables. This suggests that each variable retains its independent contribution to the model, and regression or structural analyses are not biased by multicollinearity.

Furthermore, the assumption of independence of residuals was tested. Correlation coefficients among residuals ranged from 0.023 to 0.042, with associated p-values between 0.068 and 0.112, all above the 0.05 threshold. These results confirm the absence of significant correlations among residuals, thereby supporting the independence assumption. Accordingly, the statistical model can be considered valid, and the estimates obtained are unbiased and reliable.

Construct reliability and validity were also examined. Cronbach’s alpha values for all variables exceeded 0.80, ranging from 0.80 to 0.88, indicating satisfactory internal consistency. Rho values ranged from 0.71 to 0.87, and composite reliability (CR) values were above 0.70 (0.80–0.83), further supporting adequate construct reliability. The average variance extracted (AVE) for all constructs was above 0.50, with the “death thought” variable reaching the borderline value of 0.50, which is still considered acceptable.

Overall, the results of the statistical assumption checks, along with the reliability and validity indices, indicate that the study data are of high quality, and the instruments employed are both valid and reliable. Therefore, the proposed structural model, based on the variables of loneliness, death thought, rumination, and spiritual intelligence, is methodologically and empirically supported, and the obtained results can be considered trustworthy and interpretable.

Based on the results presented in Table 2, the structural model demonstrated satisfactory fit indices. The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) was 0.043, below the recommended threshold of 0.08, indicating an excellent fit of the model to the empirical data. Additionally, the Normed Fit Index (NFI) was 0.962, exceeding the acceptable threshold of 0.90, suggesting that the proposed model provides a superior explanation of the data compared to the baseline model. Overall, these indices indicate that the structural model has an adequate fit, supporting the validity and reliability of the obtained results.

The results of the structural model (Table 3 & Figure 1) indicate that all direct and indirect paths were statistically significant. Psychological well-being had a significant positive effect on spiritual intelligence (β = 0.50, p < 0.001) and a significant negative effect on loneliness (β = -0.40, p < 0.001), rumination (β = -0.38, p < 0.001), and death-related thoughts (β = -0.30, p = 0.001). In turn, spiritual intelligence significantly reduced loneliness (β = -0.20, p = 0.011), rumination (β = -0.25, p = 0.009), and death-related thoughts (β = -0.35, p < 0.001). All indirect effects of psychological well-being on these outcomes through spiritual intelligence were also significant, highlighting the mediating role of spiritual intelligence in attenuating the negative impact of low psychological well-being on loneliness, rumination, and death-related thoughts. Overall, the model confirms both the direct and mediating influences of spiritual intelligence on key psychological outcomes among older adults.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics

Table 2. Structural model fit indices

Table 3. Direct and indirect path coefficients

| Variable | Category/Range | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

| Gender | Female | 122 | 61.0 |

| Male | 78 | 39.0 | |

| Marital Status | Married | 96 | 48.0 |

| Single/widowed | 82 | 41.0 | |

| Divorced | 22 | 11.0 | |

| Age (years) | 60–65 | 58 | 29.0 |

| 66–70 | 72 | 36.0 | |

| 71–75 | 42 | 21.0 | |

| 76 and above | 28 | 14.0 | |

| Education | Illiterate | 41 | 20.5 |

| Elementary & below diploma | 89 | 44.5 | |

| Diploma | 68 | 34.0 | |

| Bachelor’s & master’s | 2 | 1.0 |

Table 2. Structural model fit indices

| Fit index | Value | Interpretation |

| Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) | 0.043 | Good fit (< 0.08) |

| Normed Fit Index (NFI) | 0.962 | Good fit (> 0.90) |

Table 3. Direct and indirect path coefficients

| Variables | Path coefficient (β) | t-value | p |

| Loneliness →Spiritual Int. | -0.20 | 2.50 | 0.011 |

| Loneliness →Psy. WB. | -0.40 | 5.10 | 0.000 |

| Rum. → Spiritual Int. | -0.25 | 2.60 | 0.009 |

| Rum. → Psy. WB. | -0.38 | 4.80 | 0.000 |

| Death thought → Spiritual intelligence | -0.35 | 3.80 | 0.000 |

| Death thought → Psy. WB. | -0.30 | 3.30 | 0.001 |

| Spiritual intelligence → Psy. WB. | 0.50 | 6.20 | 0.000 |

| Loneliness → Spiritual Int. → Psy. WB. | -0.10 | 2.55 | 0.011 |

| Rum. → Spiritual Int. → Psy. WB. | -0.13 | 3.10 | 0.000 |

| Death thought → Spiritual Int. → Psy. WB. | -0.11 | 2.60 | 0.009 |

Figure 1. Structural model

Discussion

The present study aimed to examine the role of loneliness, death thought, and rumination on the psychological health of older adults, with a focus on the mediating role of spiritual intelligence. The findings indicated that all three negative variables (loneliness, death thought, and rumination) had a significant and direct effect on reducing psychological health, while spiritual intelligence functioned as a positive inner resource with protective and mediating roles.

About the loneliness and psychological health, the findings showed that loneliness had a significant negative effect on the psychological health of older adults. This result is consistent with studies by Somes (61), Tragantzopoulou and Giannouli (62) and Hards et al., (16), which reported that older adults who experience social isolation and loneliness are more vulnerable to depression, anxiety, and poor sleep quality. In line with studies by Mann et al., (63) and Wang et al., (64), loneliness threatens not only psychological health but also quality of life and even physical health. Given the unique conditions of aging—such as retirement, reduced social interaction, and the loss of loved ones—these findings are understandable. Thus, loneliness can be considered a key factor undermining older adults’ psychological health, highlighting the necessity of targeted psychological and social interventions.

About the death thought and psychological health, the results also showed that death thought had a significant negative impact on psychological health. This finding is consistent with Kastenbaum and Moreman (22) and Phan et al., (23), Phan et al., (25), who emphasized that persistent focus on death can serve as a major source of anxiety and distress. Similarly, Littman-Ovadia and Russo-Netzer (26) and Van Wilder et al., (65) reported that frequent death-related thoughts increase the risk of depression and anxiety, especially among those lacking effective coping resources. On the other hand, research by Halifax (27) indicated that constructive reflection on death can promote personal and spiritual growth. However, it seems that in the Iranian elderly population, death thought is more often experienced as a source of anxiety rather than growth. These findings underscore the importance of existential and spiritual interventions in mitigating the negative impact of death thought on psychological health.

About the rumination and psychological health, the findings revealed that rumination significantly and negatively influenced the psychological health of older adults. This result is consistent with studies by Nolen-Hoeksema (66), Watkins (31), and Wong et al., (32), which describe rumination as a maladaptive cognitive style that traps individuals in cycles of negative thinking and prevents effective emotional processing. Furthermore, the results are aligned with Constantin et al., (67), who found that rumination not only exacerbates anxiety and depression but also complicates the therapeutic process. In older adults, reduced cognitive resources and coping skills may amplify the harmful effects of rumination, explaining the strength of this finding.

About the spiritual intelligence and psychological health, the results indicated that spiritual intelligence had a positive and significant effect on psychological health. Older adults with higher levels of spiritual intelligence were better able to find meaning in challenging experiences, regulate negative emotions, and accept existential realities such as death. This finding is consistent with studies by Ibrahim et al., (39), Hosseinbor et al., (40), which confirmed the role of spiritual intelligence as a cognitive–existential capacity that enhances psychological well-being. Furthermore, studies by Jouybari and Ghoreishi (43) demonstrated that spiritual intelligence reduces rumination and reframes negative thoughts, thereby promoting mental health. These findings highlight the importance of spiritual intelligence as a protective resource against age-related stressors.

About the mediating role of spiritual intelligence, one of the major findings of the study was the mediating role of spiritual intelligence in the relationship between loneliness, death thought, rumination, and psychological health. The analysis showed that spiritual intelligence moderated the negative effects of these variables. In other words, older adults with higher levels of spiritual intelligence were able to reduce the harmful effects of loneliness, rumination, and death-related thoughts by engaging in meaning-making, accepting existential realities, and employing cognitive reappraisal. This finding is consistent with Zoghi and Salmani (44), who showed that spiritual intelligence not only has a direct positive impact on psychological health but also indirectly improves well-being by reducing death anxiety and supporting emotional regulation.

Conclusion

The findings of the present study indicate that loneliness, death-related thoughts, and rumination are among the key factors that undermine psychological health in older adults, each exerting a significant and direct negative effect on mental well-being. In contrast, spiritual intelligence emerged as a positive internal resource that plays a protective and enhancing role in psychological health. Older adults with higher levels of spiritual intelligence demonstrated a greater capacity to find meaning in challenging life experiences, regulate negative emotions, and accept existential realities such as aging and death. Importantly, the mediating role of spiritual intelligence suggests that it can attenuate the adverse effects of loneliness, rumination, and death-related thoughts by facilitating meaning-making processes and cognitive reappraisal. These findings highlight the importance of incorporating spiritually oriented and existentially informed interventions into mental health programs for older adults. Alongside social strategies aimed at reducing loneliness, such interventions may contribute significantly to improving psychological health and overall quality of life in later adulthood.

Study limitations

The limitations of this study include the lack of control over certain confounding variables such as physical condition, education, and religious beliefs, as well as the cross-sectional nature of the research, which prevents definitive causal inferences. Therefore, it is recommended for future studies to investigate the role of mediating and moderating variables, such as social support and coping styles, and to conduct qualitative studies to gain a deeper understanding of the experiences of older adults.

Conflict of interest

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the participants who cooperated by completing the questionnaires for this research. Their contribution was essential to this study.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Both authors contributed to the conceptualization, design, and methodology of the study. Data collection was conducted by the second author. Data analysis was performed by the second author under the supervision of the first author. Both authors participated in the interpretation of results, drafting, and critical revision of the manuscript, and approved the final version for submission.

References

1. Lee G, Chulwoo K. Social isolation and mental well-being among Korean older adults: a focus on living arrangements. Frontiers in Public Health. 2024; 12(6): 684–703.

2. Bondarchuk O, Balakhtar V, Pinchuk N, Pustovalov I, Pavlenok K. Coping with stressfull situations using coping strategies and their impact on mental health. Multidisciplinary Reviews. 2024; 7

3. Zhao K. A preliminary study of the factors affecting college students’ sense of well-being: Self-concept, mental health, interpersonal relationships, and the cultivation of all-round development ability. Studies in Psychological Science. 2024; 2(1): 48–58.

4. Quill G. Navigating the Challenges of Aging-A Mental Health Guide: Practical Mental Health Tips for Seniors: Gaius Quill Publishing: 2024.

5. Sharma G, Morishetty SK. Common mental and physical health issues with elderly: a narrative review. ASEAN Journal of Psychiatry. 2022; 23(1): 1–11.

6. Győri Á. The impact of social-relationship patterns on worsening mental health among the elderly during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from Hungary. SSM-Population Health. 2023; 21: 1-13.

7. Newman-Norlund RD, Newman-Norlund SE, Sayers S, McLain AC, Riccardi N, Fridriksson J. Effects of social isolation on quality of life in elderly adults. PloS One. 2022; 17(11): 1-14.

8. Brandt L, Liu S, Heim C, Heinz A. The effects of social isolation stress and discrimination on mental health. Translational Psychiatry. 2022; 12(1): 1-11.

9. Reynolds 3rd CF, Jeste DV, Sachdev PS, Blazer DG. Mental health care for older adults: recent advances and new directions in clinical practice and research. World Psychiatry. 2022; 21(3): 336–63.

10. O‘G‘Li ASN. The importance of social activity in old age: a key factor for psychological well-being. Eurasian Journal of Social Sciences, Philosophy and Culture. 2024; 4(10): 12–6.

11. da Silva THR. Loneliness in older adults. British Journal of Community Nursing. 2024; 29(2): 60–6.

12. Prizeman K, Weinstein N, McCabe C. Effects of mental health stigma on loneliness, social isolation, and relationships in young people with depression symptoms. BMC Psychiatry. 2023; 23(1): 1-15.

13. Yuldasheva MB, Samindjonova ZI. Socio-psychological meta-analysis of the concepts of “Loneliness”, “Solitude” and “Isolation”. Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education. 2023; 9(4): 471–7.

14. Thompson A, Smith MA, McNeill A, Pollet TV. Friendships, loneliness and psychological wellbeing in older adults: a limit to the benefit of the number of friends. Ageing & Society. 2024; 44(5): 1090–115.

15. Meng L, Xu R, Li J, Hu J, Xu H, Wu D, et al. The silent epidemic: exploring the link between loneliness and chronic diseases in China’s elderly. BMC Geriatrics. 2024; 24(1): 1-14.

16. Hards E, Loades ME, Higson‐Sweeney N, Shafran R, Serafimova T, Brigden A, et al. Loneliness and mental health in children and adolescents with pre‐existing mental health problems: A rapid systematic review. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2022; 61(2): 313–34.

17. Haslam SA, Haslam C, Cruwys T, Jetten J, Bentley SV, Fong P, et al. Social identity makes group-based social connection possible: Implications for loneliness and mental health. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2022; 43: 161–5.

18. Freak-Poli R, Kung CS, Ryan J, Shields MA. Social isolation, social support, and loneliness profiles before and after spousal death and the buffering role of financial resources. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2022; 77(5): 956–71.

19. Kotwal AA, Cenzer IS, Waite LJ, Covinsky KE, Perissinotto CM, Boscardin WJ, et al. The epidemiology of social isolation and loneliness among older adults during the last years of life. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2021; 69(11): 3081–91.

20. Wolters NE, Mobach L, Wuthrich VM, Vonk P, Van der Heijde CM, Wiers RW, et al. Emotional and social loneliness and their unique links with social isolation, depression and anxiety. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2023; 329: 207–17.

21. Zhang Y, Kuang J, Xin Z, Fang J, Song R, Yang Y, et al. Loneliness, social isolation, depression and anxiety among the elderly in Shanghai: Findings from a longitudinal study. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2023; 110: 104980.

22. Kastenbaum R, Moreman CM. Death, society, and human experience. Routledge; 2024.

23. Phan HP, Chen SC, Ngu BH, Hsu CS. Advancing the study of life and death education: theoretical framework and research inquiries for further development. Frontiers in Psychology. 2023; 14: 1-13.

24. Pandya Ak, Kathuria T. Death anxiety, religiosity and culture: Implications for therapeutic process and future research. Religions. 2021; 12(1): 1-13.

25. Phan HP, Ngu BH, Chen SC, Wu L, Shih JH, Shi SY. Life, death, and spirituality: A conceptual analysis for educational research development. Heliyon. 2021; 7(5): 1-10.

26. Littman-Ovadia H, Russo-Netzer P. Exploring the lived experience and coping strategies of Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) among emerging adults. Current Psychology. 2024; 43: 1–21.

27. Halifax J. Being with dying: Cultivating compassion and fearlessness in the presence of death. Shambhala Publications; 2024.

28. Zhang J, Cao Y, Su M, Cheng J, Yao N. The experiences of clinical nurses coping with patient death in the context of rising hospital deaths in China: a qualitative study. BMC Palliative Care. 2022; 21(1): 1-9.

29. Üzar-Özçetin YS, Budak SE, editors. The relationship between attitudes toward death, rumination, and psychological resilience of oncology nurses. Seminars in Oncology Nursing; Elsevier: 2024.

30. Joubert AE, Moulds ML, Werner‐Seidler A, Sharrock M, Popovic B, Newby JM. Understanding the experience of rumination and worry: A descriptive qualitative survey study. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2022; 61(4): 929–46.

31. Watkins E. Rumination. In: Dozois DJA, Dobson KS, editors. Treatment of psychosocial risk factors in depression American Psychological Association; 2023. p. 305-31.

32. Wong SM, Chen EY, Lee MC, Suen Y, Hui CL. Rumination as a Transdiagnostic phenomenon in the 21st century: the flow model of rumination. Brain Sciences. 2023; 13(7): 1-17.

33. Ciobotaru D, Jones CJ, Cohen Kadosh R, Violante IR, Cropley M. “Too much of a burden”: Lived experiences of depressive rumination in early adulthood. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2024; 71(4): 255-67.

34. Rickerby N, Krug I, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Forte E, Davenport R, Chayadi E, et al. Rumination across depression, anxiety, and eating disorders in adults: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2024; 31(2): 251-68.

35. Bean CA, Ciesla JA. Ruminative variability predicts increases in depression and social anxiety. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2024; 48(3): 511–25.

36. McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination as a transdiagnostic factor in depression and anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2011; 49(3): 186–93.

37. Ye N, Peng L, Deng B, Hu H, Wang Y, Zheng T, et al. Repetitive negative thinking is associated with cognitive function decline in older adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2025; 25(1): 1-8.

38. Mancone S, Celia G, Bellizzi F, Zanon A, Diotaiuti P. Emotional and cognitive responses to romantic breakups in adolescents and young adults: the role of rumination and coping mechanisms in life impact. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2025; 16: 1-13.

39. Ibrahim N, Burhan NM, Mohamed A, Mahmud M, Abdullah SR. Emotional intelligence, spiritual intelligence and psychological well-being: Impact on society. Malaysian Journal of Society and Space. 2022; 18(3): 90–103.

40. Hosseinbor M, Jadgal MS, Kordsalarzehi F. Relationship between spiritual well-being and spiritual intelligence with mental health in students. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. 2021; 35(2): 197–201.

41. Pant N, Srivastava SK. The impact of spiritual intelligence, gender and educational background on mental health among college students. Journal of Religion and Health. 2019; 58(1): 87–108.

42. Pinto CT, Guedes L, Pinto S, Nunes R. Spiritual intelligence: a scoping review on the gateway to mental health. Global Health Action. 2024; 17(1): 1-16.

43. Jouybari FT, Ghoreishi MK. Predicting rumination based on spiritual intelligence, cognitive flexibility, and self-esteem. Journal of Fundamentals of Mental Health. 2025; 27(2): 131-8.

44. Zoghi L, Salmani M. The relationship between spiritual intelligence and general health in the elderly: the mediating role of mindfulness. Aging Psychology. 2022; 8(4): 349–60.

45. Polemikou A, Vantarakis S. Death anxiety and spiritual intelligence as predictors of dissociative posttraumatic stress disorder in Greek first responders: A moderation model. Spirituality in Clinical Practice. 2019; 6(3): 182-93.

46. Salmani M, Zoghi L. The relationship between loneliness, spiritual intelligence and general health with death anxiety in the elderly: the mediating role of mindfulness. Psychology. 2022; 8(1): 39–54.

47. Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford publications: 2023.

48. Russell D, Peplau LA, Ferguson ML. Developing a measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1978; 42(3): 290–4.

49. Larijani M, Moslehi M. Older women's perception of loneliness and virtual actions adapt to it. Women s Studies (Sociological & Psychological). 2022; 20(1): 65–98.

50. Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989; 57(6): 1069-81.

51. Ryff CD, Singer BH. Best news yet on the six-factor model of well-being. Social Science Research. 2006; 35(4): 1103–19.

52. Vafanoush M, Farah Bakhsh K, Bajestani HS, Farrokhi N. Investigating the lived experiences of the elderly in Tehran in relation to psychological well-being and comparing it with the psychological well-being of Ryff. Journal of Applied Research in Counseling. 2024; 6(3): 53–67. [Persian]

53. Templer DI. The construction and validation of a death anxiety scale. The Journal of General Psychology. 1970; 82(2): 165–77.

54. Downey L, Curtis JR, Lafferty WE, Herting JR, Engelberg RA. The Quality of Dying and Death Questionnaire (QODD): empirical domains and theoretical perspectives. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2010; 39(1): 9–22.

55. Sharif Nia H, Sharif SP, Goudarzian AH, Haghdoost AA, Ebadi A, Soleimani MA. An evaluation of psychometric properties of the Templer's Death Anxiety Scale-Extended among a sample of Iranian chemical warfare veterans. Journal of Hayat. 2016; 22(3): 229–44. [Persian]

56. Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991; 61(1): 115-21.

57. Treynor W, Gonzalez R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003; 27(3): 247–59.

58. Babaahmadi Milani F, Momeni K, Dehghani-Arani F, Beyramvand Y, Setoudehmaram S, Saffarifard R. The mediating role of rumination in the relationship between high school students with borderline personality disorder and self-Injury. Journal of Applied Psycology Research. 2023; 14(1): 85–98. [Persian]

59. King DB, DeCicco TL. A viable model and self-report measure of spiritual intelligence. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies. 2009; 28(1): 68-85.

60. Sharif Nia H, Haghdoost AA, Ebadi A, Soleimani MA, Yaghoobzadeh A, Abbaszadeh A, et al. Psychometric properties of the king spiritual intelligence questionnaire (ksiq) in physical veterans of iran-iraq warfare. Journal of Military Medicine. 2015; 17(3): 145–53. [Persian]

61. Somes J. The loneliness of aging. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2021; 47(3): 469–75.

62. Tragantzopoulou P, Giannouli V. Social isolation and loneliness in old age: Exploring their role in mental and physical health. Psychiatriki. 2021; 32(1): 59–66.

63. Mann F, Wang J, Pearce E, Ma R, Schlief M, Lloyd-Evans B, et al. Loneliness and the onset of new mental health problems in the general population. Social Psychiatry and Ppsychiatric Epidemiology. 2022; 57(11): 2161–78.

64. Wang S, Quan L, Chavarro JE, Slopen N, Kubzansky LD, Koenen KC, et al. Associations of depression, anxiety, worry, perceived stress, and loneliness prior to infection with risk of post–COVID-19 conditions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022; 79(11): 1081–91.

65. Van Wilder L, Pype P, Mertens F, Rammant E, Clays E, Devleesschauwer B, et al. Living with a chronic disease: insights from patients with a low socioeconomic status. BMC Family Practice. 2021; 22(1): 1-11.

66. Nolen-Hoeksema S. The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000; 109(3): 504-11.

67. Constantin K, English MM, Mazmanian D. Anxiety, depression, and procrastination among students: Rumination plays a larger mediating role than worry. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy. 2018; 36(1): 15–27.

The present study aimed to examine the role of loneliness, death thought, and rumination on the psychological health of older adults, with a focus on the mediating role of spiritual intelligence. The findings indicated that all three negative variables (loneliness, death thought, and rumination) had a significant and direct effect on reducing psychological health, while spiritual intelligence functioned as a positive inner resource with protective and mediating roles.

About the loneliness and psychological health, the findings showed that loneliness had a significant negative effect on the psychological health of older adults. This result is consistent with studies by Somes (61), Tragantzopoulou and Giannouli (62) and Hards et al., (16), which reported that older adults who experience social isolation and loneliness are more vulnerable to depression, anxiety, and poor sleep quality. In line with studies by Mann et al., (63) and Wang et al., (64), loneliness threatens not only psychological health but also quality of life and even physical health. Given the unique conditions of aging—such as retirement, reduced social interaction, and the loss of loved ones—these findings are understandable. Thus, loneliness can be considered a key factor undermining older adults’ psychological health, highlighting the necessity of targeted psychological and social interventions.

About the death thought and psychological health, the results also showed that death thought had a significant negative impact on psychological health. This finding is consistent with Kastenbaum and Moreman (22) and Phan et al., (23), Phan et al., (25), who emphasized that persistent focus on death can serve as a major source of anxiety and distress. Similarly, Littman-Ovadia and Russo-Netzer (26) and Van Wilder et al., (65) reported that frequent death-related thoughts increase the risk of depression and anxiety, especially among those lacking effective coping resources. On the other hand, research by Halifax (27) indicated that constructive reflection on death can promote personal and spiritual growth. However, it seems that in the Iranian elderly population, death thought is more often experienced as a source of anxiety rather than growth. These findings underscore the importance of existential and spiritual interventions in mitigating the negative impact of death thought on psychological health.

About the rumination and psychological health, the findings revealed that rumination significantly and negatively influenced the psychological health of older adults. This result is consistent with studies by Nolen-Hoeksema (66), Watkins (31), and Wong et al., (32), which describe rumination as a maladaptive cognitive style that traps individuals in cycles of negative thinking and prevents effective emotional processing. Furthermore, the results are aligned with Constantin et al., (67), who found that rumination not only exacerbates anxiety and depression but also complicates the therapeutic process. In older adults, reduced cognitive resources and coping skills may amplify the harmful effects of rumination, explaining the strength of this finding.

About the spiritual intelligence and psychological health, the results indicated that spiritual intelligence had a positive and significant effect on psychological health. Older adults with higher levels of spiritual intelligence were better able to find meaning in challenging experiences, regulate negative emotions, and accept existential realities such as death. This finding is consistent with studies by Ibrahim et al., (39), Hosseinbor et al., (40), which confirmed the role of spiritual intelligence as a cognitive–existential capacity that enhances psychological well-being. Furthermore, studies by Jouybari and Ghoreishi (43) demonstrated that spiritual intelligence reduces rumination and reframes negative thoughts, thereby promoting mental health. These findings highlight the importance of spiritual intelligence as a protective resource against age-related stressors.

About the mediating role of spiritual intelligence, one of the major findings of the study was the mediating role of spiritual intelligence in the relationship between loneliness, death thought, rumination, and psychological health. The analysis showed that spiritual intelligence moderated the negative effects of these variables. In other words, older adults with higher levels of spiritual intelligence were able to reduce the harmful effects of loneliness, rumination, and death-related thoughts by engaging in meaning-making, accepting existential realities, and employing cognitive reappraisal. This finding is consistent with Zoghi and Salmani (44), who showed that spiritual intelligence not only has a direct positive impact on psychological health but also indirectly improves well-being by reducing death anxiety and supporting emotional regulation.

Conclusion

The findings of the present study indicate that loneliness, death-related thoughts, and rumination are among the key factors that undermine psychological health in older adults, each exerting a significant and direct negative effect on mental well-being. In contrast, spiritual intelligence emerged as a positive internal resource that plays a protective and enhancing role in psychological health. Older adults with higher levels of spiritual intelligence demonstrated a greater capacity to find meaning in challenging life experiences, regulate negative emotions, and accept existential realities such as aging and death. Importantly, the mediating role of spiritual intelligence suggests that it can attenuate the adverse effects of loneliness, rumination, and death-related thoughts by facilitating meaning-making processes and cognitive reappraisal. These findings highlight the importance of incorporating spiritually oriented and existentially informed interventions into mental health programs for older adults. Alongside social strategies aimed at reducing loneliness, such interventions may contribute significantly to improving psychological health and overall quality of life in later adulthood.

Study limitations

The limitations of this study include the lack of control over certain confounding variables such as physical condition, education, and religious beliefs, as well as the cross-sectional nature of the research, which prevents definitive causal inferences. Therefore, it is recommended for future studies to investigate the role of mediating and moderating variables, such as social support and coping styles, and to conduct qualitative studies to gain a deeper understanding of the experiences of older adults.

Conflict of interest

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the participants who cooperated by completing the questionnaires for this research. Their contribution was essential to this study.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Both authors contributed to the conceptualization, design, and methodology of the study. Data collection was conducted by the second author. Data analysis was performed by the second author under the supervision of the first author. Both authors participated in the interpretation of results, drafting, and critical revision of the manuscript, and approved the final version for submission.

References

1. Lee G, Chulwoo K. Social isolation and mental well-being among Korean older adults: a focus on living arrangements. Frontiers in Public Health. 2024; 12(6): 684–703.

2. Bondarchuk O, Balakhtar V, Pinchuk N, Pustovalov I, Pavlenok K. Coping with stressfull situations using coping strategies and their impact on mental health. Multidisciplinary Reviews. 2024; 7

3. Zhao K. A preliminary study of the factors affecting college students’ sense of well-being: Self-concept, mental health, interpersonal relationships, and the cultivation of all-round development ability. Studies in Psychological Science. 2024; 2(1): 48–58.

4. Quill G. Navigating the Challenges of Aging-A Mental Health Guide: Practical Mental Health Tips for Seniors: Gaius Quill Publishing: 2024.

5. Sharma G, Morishetty SK. Common mental and physical health issues with elderly: a narrative review. ASEAN Journal of Psychiatry. 2022; 23(1): 1–11.

6. Győri Á. The impact of social-relationship patterns on worsening mental health among the elderly during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from Hungary. SSM-Population Health. 2023; 21: 1-13.

7. Newman-Norlund RD, Newman-Norlund SE, Sayers S, McLain AC, Riccardi N, Fridriksson J. Effects of social isolation on quality of life in elderly adults. PloS One. 2022; 17(11): 1-14.

8. Brandt L, Liu S, Heim C, Heinz A. The effects of social isolation stress and discrimination on mental health. Translational Psychiatry. 2022; 12(1): 1-11.

9. Reynolds 3rd CF, Jeste DV, Sachdev PS, Blazer DG. Mental health care for older adults: recent advances and new directions in clinical practice and research. World Psychiatry. 2022; 21(3): 336–63.

10. O‘G‘Li ASN. The importance of social activity in old age: a key factor for psychological well-being. Eurasian Journal of Social Sciences, Philosophy and Culture. 2024; 4(10): 12–6.

11. da Silva THR. Loneliness in older adults. British Journal of Community Nursing. 2024; 29(2): 60–6.